Investors are slowly starting to believe the story of Türkiye’s U-turn.

Capital inflows into the country’s stock market turned positive in November and reached more than $1 billion a week in December, according to research firm GlobalSource Partners. The yield on the benchmark 10-year dollar-denominated Treasury note has fallen 200 basis points in the past two months to about 7%. The central bank’s foreign exchange reserves have increased by 40% since their lows this summer.

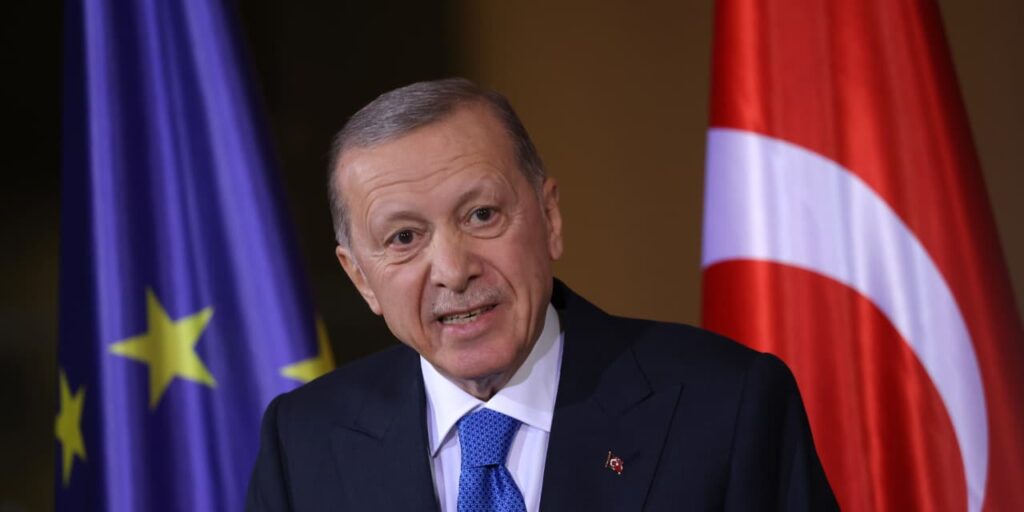

Promoting this good mood is this year’s economic policy surprises. Turkish leader Recep Erdogan turned to Orthodoxy after being re-elected as president in May. Despite Turkey’s annual inflation rate soaring to 80%, campaigner President Recep Tayyip Erdogan scorned any idea of austerity. He claimed that high interest rates cause inflation, but Economics 101 teaches the opposite.

She installed a new central bank governor, Hafize Erkan, who raised interest rates from 8% to 42.5% in June and which economists expect to rise further to 45% in January. She and Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek, a former investment banker and market favorite, have gutted regulations that steered subsidized loans to favored borrowers.

Six months have passed since then, and President Erdoğan’s conversion seems to be gaining momentum. “I think President Erdoğan understands the seriousness of the inflation situation,” said Emre Akçamak, a senior consultant at East Capital. “We are almost back to orthodox policy.”

Advertisement – SCROLL TO CONTINUE

However, increasing Turkey’s inflation rate is a multi-year task. The central bank predicts that this number will reach single digits only in 2026, but even that target may be too optimistic. “Inflation may be stronger than we think,” said Murat Yusa, Turkey economist at GlobalSource Partners.

It is difficult to imagine that President Erdogan, who has been an incendiary populist for most of his two decades in power, will continue down such a difficult path. The lira has lost nearly 95% of its value over the past decade.

“When traditional policy becomes really painful, you don’t want to be around,” said Edward Al Hussaini, head of emerging markets fixed income research at Columbia Threadneedle Investments. He continues to hold Turkish hard currency bonds anyway, believing the reform axis will bring back investors who have fled the market. “This is a very underrated name,” Al Hussaini said. “The asset price correction is probably about two-thirds of the way through.”

For stock investors, the math is even more complex. iShares MSCI Türkiye

Advertisement – SCROLL TO CONTINUE

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have fallen 15% since Oct. 1, erasing the bull run since President Recep Tayyip Erdogan first brought in Erkan Simsek’s dream team. The central bank’s spectacular interest rate hikes have pushed bank deposit rates up to about 50% a year, driving local investors out of the stock market, Akciamak said.

He remains bullish on consumer staples companies, predicting they will eat into market share as tight finances force Turks to become more frugal. The top companies in this category, discount retailer BIM Birlesik Magazalar, beer company Anadolu Efes and Coca-Cola Icecek, continue to rise even as market indexes fall.

David Aselkov, JPMorgan’s emerging Europe and Middle East equity strategist, added that domestically-focused companies are on the right side of macroeconomic shifts. With the lira down 17%, their profits should at least keep pace with inflation, but JPMorgan still sees inflation at 40% by the end of next year, which would mean rising profits in dollar terms. Exporters will suffer from the opposite logic, as their costs grow faster than revenues. “The sweet spot now is domestically-produced essentials,” he said.

Advertisement – SCROLL TO CONTINUE

The broader discussion on Turkish stocks revolves around valuation and positioning. Akkakmak believes that Turkey is very cheap compared to other emerging markets, with an average forward price/earnings ratio of 3.9 times, which is somewhat cheap compared to Turkey’s history. “This is the fifth time in the last 15 years that we’ve been close to this level, and each time we’ve seen an increase,” he said.

Aselkov added that foreign ownership of Turkish shares has fallen by half over the past four years, creating conditions for a recovery. “The story of 2024 will be foreign investors entering the market,” he said.

Unless, of course, President Erdogan changes his mind again. The president, who has steadily attacked Congress, the judiciary, the central bank, and the press, can and does change the course of a nation of 86 million people almost at will. Some investors won’t go along with it at any cost. “There is a long record of institutional deterioration that affects every branch of government,” said Sammy Mouadi, emerging market fixed income portfolio manager at T. Rowe Price.

The Turks themselves are hopeful but wounded, Akcamak said. “This is one of the most resilient countries,” he said. “But people are pretty tired because the environment is totally different every year.”

Please contact editors@barrons.com