It’s only fitting that the first scene of Diane von Furstenberg: Woman in Charge, a new Hulu documentary about the fashion designer, opens with an archival clip of David Letterman introducing her as “the woman who reinvented dress.” For much of her career, von Furstenberg (known as DVF) was synonymous with the wrap dress, and the clothes she designed 50 years ago have become symbols of female empowerment.

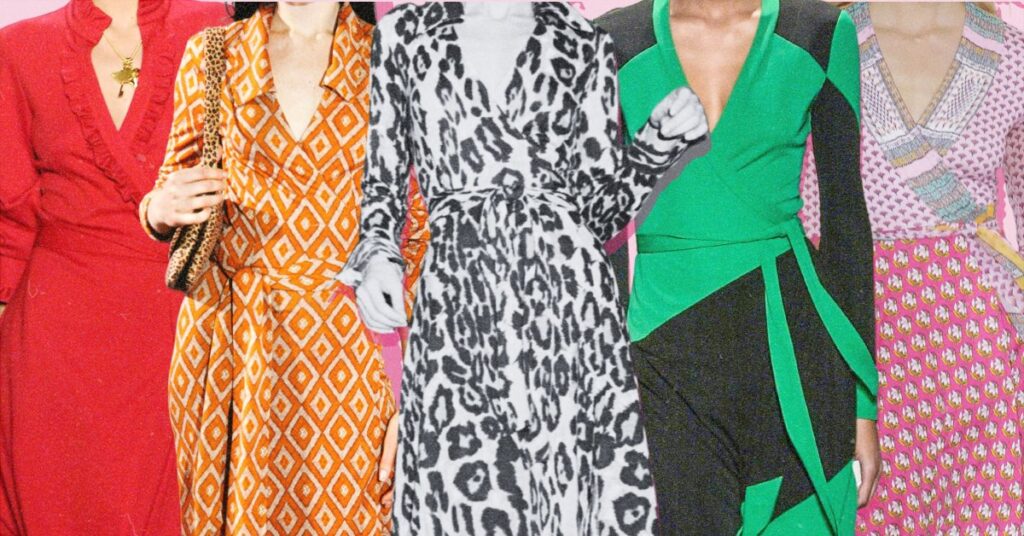

While the wrap dress as we know it today is considered a classic (and a go-to staple in the working woman’s wardrobe), when von Furstenberg first introduced her design in 1974, it was revolutionary. Inspired by early wrap-around garments in Asia, versions of the wrap dress existed before von Furstenberg’s, but her dress became a phenomenon because it captured the spirit of an era when American culture was rapidly being shaped by movements like women’s liberation and the sexual revolution. Made from stretchy silk jersey, DVF’s wrap dresses, with their V-necks, tie waists, and below-the-knee skirts, were comfortable, lightweight, and flattering. They offered a stark contrast to the restrictive clothing and masculine suits often required of working women. Available in a variety of bold, eye-catching prints, from bold leopard prints to colorful geometrics, the jersey dresses were fun yet practical, neat yet sexy, and a powerful reminder that women are not monolithic.

Read more: Diane von Furstenberg wants you to know that she gets depressed sometimes, too

Von Furstenberg had favored silk jersey and playful prints since launching her eponymous label in 1970, but was inspired to create the wrap dress after seeing Julie Nixon Eisenhower wearing a printed jersey wraparound blouse and skirt set from DVF during a television appearance during the Watergate scandal. By creating a stylish, effortless piece that women could wear for work and play, von Furstenberg streamlined the getting ready process without sacrificing style. Fairly reasonably priced (its initial debut retailed for $80 in 1974), it became a versatile and bold uniform for busy modern women, allowing women to wear the DVF wrap dress to the office and then out on the town after work. In the documentary, Vanessa Friedman, chief fashion critic for The New York Times, points out that the dress’s power to embody the changing roles of women at the time was the reason it had such an impact on fashion history.

“This dress empowered a lot of women who could afford to wear it, which, let’s be honest, most luxury fashion doesn’t,” Friedman says. “Diane’s dress sits smack in the middle of a history of women’s rights, women in the workforce, and women finding their voice.”

May 1974: Left to right: artist Andy Warhol, fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg, and actress Monique Van Vooren in New York City. Von Furstenberg wears one of her designs, a leopard-print wrap dress. Photo: Tim Boxer/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

May 1974: Left to right: artist Andy Warhol, fashion designer Diane von Furstenberg, and actress Monique Van Vooren in New York City. Von Furstenberg wears one of her designs, a leopard-print wrap dress. Photo: Tim Boxer/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

For von Furstenberg, the wrap dress as a pioneering symbol of feminist style has a deeply personal meaning, reflecting her own journey to finding empowerment as a feminist and entrepreneur in a fashion industry that was predominantly male-dominated at the time. Born Diane Halfin in Belgium to a mother who was a Holocaust survivor, von Furstenberg was told from an early age that “fear is not an option” and learned to embrace her otherness as a Jewish girl in the homogenous non-Jewish community she grew up in. After marrying Egon von Furstenberg, a German prince and member of the jet set whose family frowned upon Diane’s Jewish heritage, von Furstenberg refused to be limited by her husband’s title or seen as merely a society wife, and was determined to launch her own fashion line and have her own career and identity, even if it never hurt her husband’s social and economic capital in launching a new business. When the couple separated in 1972, just three years after marrying and having two children (they eventually officially divorced in 1983), von Furstenberg saw the breakup as a seminal moment in her development as both a designer and a person, and two years later she designed the wrap dress to international acclaim.

Read more: 10 Questions with Diane von Furstenberg

“I became the woman I wanted to be,” she says of her divorce in the documentary. “I was in control of my destiny, I was raising my kids, I was in charge of my life, I was in charge of my business, I was a responsible woman.”

When von Furstenberg first introduced the wrap dress in a full-page ad in Women’s Wear Daily in 1974, she featured herself wearing it with the tagline, “Dress like a woman!” The ad’s message was clear: being an empowered woman doesn’t mean shying away from femininity or sex appeal, but rather defining who you want to be as a woman, for yourself, on your own terms. In fact, the appeal of the wrap dress for many, then and now, is in the spirit of the DVF woman, who exudes both a bold independence and glamour, perhaps reminiscent of von Furstenberg herself. Von Furstenberg was just as happy partying at Studio 54 as she was leading her own brand or doing philanthropic work.

Read more: Diane von Furstenberg’s heroes have nothing to do with fashion

Von Furstenberg’s uncompromising approach to life and style clearly resonated with women; within a year of the dress’s release, von Furstenberg was producing 25,000 dresses a week. By 1976, she had sold one million wrap dresses and appeared on the cover of Newsweek, making her one of the first female designers to achieve commercial success on that scale. And the DVF wrap dress’s influence continues: from its memorable appearance by actor Cybill Shepherd in 1976’s Taxi Driver to being worn by some of the world’s most famous women, including Michelle Obama, Kate Middleton, Oprah Winfrey and Madonna, the wrap dress has remained a timeless and beloved part of the modern woman’s wardrobe for half a century.

“I remember as a young reporter saving up to buy a Diane von Furstenberg wrap dress,” Winfrey says in the documentary. “It was a status symbol to own that dress.”

For von Furstenberg, designing the wrap dress was a way to envision her future. She created dresses for the kind of woman she wanted to be: independent, ambitious, and above all, liberated. As she states in the documentary, her goal wasn’t to make fashion history, but to “be a responsible woman, a free woman…fashion became a vehicle to achieve that.” With the wrap dress, she achieved both.