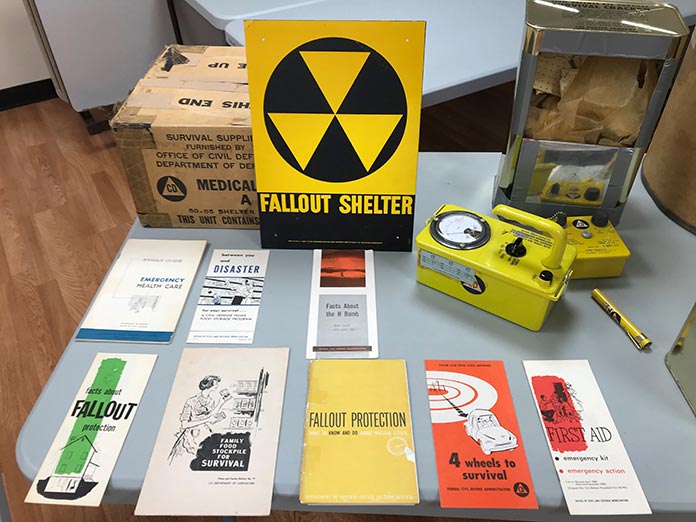

Teacher Jeff Brown brought along some artifacts from the time when the fallout shelters were being built. (Photo: Chris Lundy)

Teacher Jeff Brown brought along some artifacts from the time when the fallout shelters were being built. (Photo: Chris Lundy)

BERKELEY – Cramped space. Food and water are rationed. There’s not much to do except sit and wait.

But it’s better than being outside exposed to radiation.

The Berkeley Township Historical Society hosted a speaker who brought actual items from the bomb shelter and explained the feelings of those concerned about rising tensions between the U.S. and Russia.

Jeff Brown, a history teacher at Southern Regional, said his students respond well to the artifacts he brings in. They bring reality to students. Looking at the cover of Time magazine gives them an idea of what people were thinking at the time. Showing the rations people were supposed to eat at the evacuation shelters gives kids born 40 or 50 years later a sense of what it was like back then.

People at the historical society were similarly intrigued, some sharing stories from the Cold War and things that had been passed down to them.

Photo by Chris Landy

Photo by Chris Landy

Brown touched on the politics behind the construction of these fallout shelters. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller met with President Kennedy and urged him to build them. President Kennedy urged Congress to build them, but friends criticized it as a “great way to save the Republicans,” because at the time, Republicans lived in the suburbs and the countryside. And to some extent, they still do.

Brown briefly explained why nuclear weapons create mushroom clouds, what radiation does and why it’s dangerous, which left the audience wondering whether a fallout shelter would actually work.

“Even if that doesn’t work, the important thing is that there is a plan,” he said. This means the federal government is telling the public that, whether that plan works or not, there is a plan for the worst case scenario. This was also intended to calm the public.

The general consensus was that while it may be possible to delay the effects of radiation, it would not guarantee 100% safety.

“It was mostly theoretical, based on the low-yield weapons used in Japan,” Brown said.

We were scheduled to stay at the shelter for about two weeks. But what were those two weeks like?

Photo by Chris Landy

Photo by Chris Landy

Brown showed me some of the items being stockpiled in evacuation shelters. He had a can of water, still full and unopened, that was still drinkable. Public shelters were rationing one quart of water per person per day. This, combined with the low calorie content of the food being stockpiled, meant that for two weeks we would end up dehydrated and malnourished. And two weeks later, we would open the door to a brave new world where radiation would be gone.

A packet of crackers was handed out to the crowd from an opened ration, and a few brave souls took it. The verdict? “A taste of despair.” To get the taste out of their mouths, they quickly devoured snacks provided, not by the rations, but by members of the historical society.

Speaking of snacks, the shelters also had candy — sweet, cereal-like treats that provided carbohydrates to help people maintain weight during their self-imposed incarceration — but one of the dyes they used was the infamous red color that was later found to be carcinogenic.

The less said about portable toilets, the better.

The crackers in this can were given to others. (Photo by Chris Lundy)

The crackers in this can were given to others. (Photo by Chris Lundy)

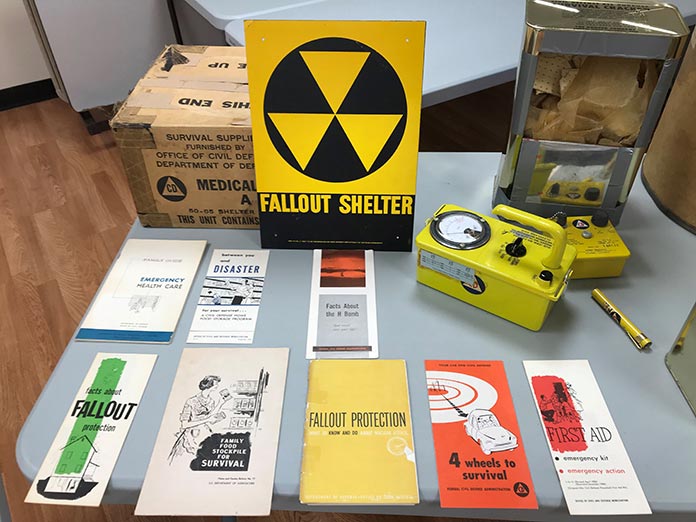

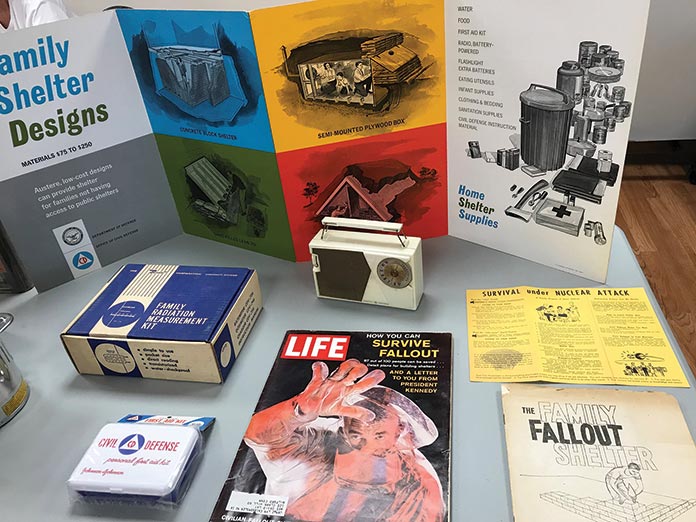

Battery-powered radios are still important to have in the home in case of emergencies. Home radiation test kits are less likely to be kept in the home.

Some of the brand names used on food and equipment are still in existence today.

These public shelters were closed in the 1970s, but some still remain, like hidden time capsules.

Brown said he knows of three public shelters in Ocean County: one at the Ocean County Courthouse, one at the BOMARC missile facility near the joint base and a third, Texas Tower 4, 85 miles off the coast of Long Beach Island. Its mission was to spot enemy submarines. The tower was lost in northeasterly winds in 1961. The 28 crew members were missing after Air Force superiors did not allow them to evacuate.

Public versions of these shelters were hidden inside schools and other buildings, marked with yellow and black radiation symbols. They were also reportedly found when collapsing bridges. However, people were expected to build them on their own land. These were not inspected, and were not listed on building plans, so it is unclear how many people actually built them. There are thought to have been around 200,000 across the country.

They were somewhat expensive to build and required land to build on, so they were thought to be built by the middle and upper classes. There were even private companies that could be hired to build them.

The shelter itself wasn’t very big and it didn’t necessarily have plenty of supplies, so what would you do if someone knocked on the door and wanted to use the shelter? The question became, “Do you love your neighbor or point your gun at your neighbor?”

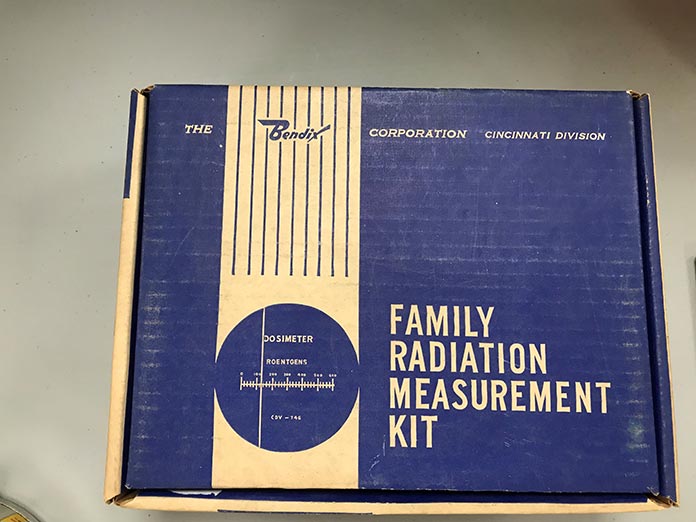

Members of the Berkeley Historical Society listen to Jeff Brown give a lecture on fallout shelters. (Photo by Chris Landy)

Members of the Berkeley Historical Society listen to Jeff Brown give a lecture on fallout shelters. (Photo by Chris Landy)

This is another reason why the total number of shelters is unknown: if you have a shelter at home, you may not want to let everyone know about it in case the whole street rushes to the shelter.

If you can build a home in the suburbs or countryside, why build one? What is the threat level on the Jersey Shore?

Ocean County is a popular target area, he said, because of the joint base, Oyster Creek and its location between New York and Philadelphia.

The impact of this era was far-reaching, Brown explained: The government’s civil defense arm that developed these plans would eventually evolve into the Federal Emergency Management Agency.