Sure, this sounds like the beginning of a joke: “A presidential assassin, a pioneering automaker, and an Academy Award-winning actress walk into a bar…”

But that’s not the case.

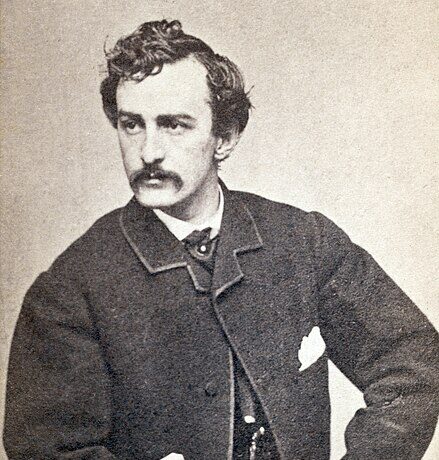

This (very) true story begins on the night of Good Friday in 1865, when John Wilkes Booth made American history by jumping from the presidential chair at Ford’s Theatre in Washington. Captured and killed after a 12-day manhunt, Booth was quickly buried without his body being shown to the public, which was perfectly fine for most Americans, who wanted to forget the ugliness of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination.

But Booth’s secret burial sparked conspiracy theories that spread rapidly throughout a still-divided nation, and rumors that Booth was not the man who was shot in the tobacco shack continued to circulate for the next 50 years.

The delusion reached a climax in 1907 with the publication of The Escape and Suicide of John Wilkes Booth.

Author Finis L. Bates was born and raised on a Mississippi plantation before the Civil War, but his family moved to Texas, where Bates became a lawyer, and it was in the Lone Star State that he first heard strange stories.

As Bates describes in his 309-page book, in Granbury, Texas, he met a town celebrity known for reciting long passages of Shakespeare (Shakespeare was Booth’s speciality in acting). He was known by names like John St. Helen.

During her illness in the late 1870s, St. Helen reportedly told Bates, “My name is John Wilkes Booth, assassin of President Lincoln. Please inform my brother (famous actor) Edwin Booth in New York City.” St. Helen recovered and then left town, never to be seen in Granbury again.

Bates initially thought the story was a lie, but the more he thought about it, the more intrigued he became. In 1900, he wrote to the War Department claiming the $100,000 reward that had been offered in 1865 for Booth’s capture. (The reward was never awarded.)

Then in 1903, Bates was reading a newspaper when a photo caught his eye. He was then a lawyer in Memphis, Tennessee, but a strange story he had heard 25 years earlier still haunted him. Bates read about a man named David E. George who had committed suicide in a hotel room in Enid, Oklahoma. After a suicide attempt nine months earlier, the man had reportedly said, “I am the greatest man-killer that ever lived. I am J. Wilkes Booth.” The article was accompanied by a photo of George’s embalmed body.

Perhaps Bates recognized the face of John St. Helen, or perhaps George summoned him as he lay dying, but either way, the lawyer quickly hopped on a train and headed for Oklahoma.

The whole thing had been strange up until then, but it soon became surreal.

Since no one wanted a fully embalmed body, the undertaker sat it in a chair in a window with its eyes open and a newspaper in hand to attract attention. Over the course of eight years, 10,000 people gazed upon the body. When the novelty wore off and no one wanted the body anymore, it was placed in the garage of Bates’ Memphis home.

That’s where Henry Ford comes in. This early automotive titan found himself mired in controversy when, in a 1916 Chicago newspaper article, he said, “History is more or less nonsense. It’s tradition. We don’t want traditions. We want to live in today. And the only history worth tinkering with is the history we make today.”

As a result, the assembly line managers who were churning out Model Ts were forced to resort to mass production damage control.

In 1919, Ford learned of Bates’ book and believed that verifying Booth’s claim that he had escaped would support his claim that “history is a hoax.” He had researchers look into the book. He invited Bates to Michigan, where Bates offered to sell George’s body to him. Ford’s researchers were unable to verify most of the claims in the book, so Ford gave up on the mummy.

Bates eventually rented it to a showman, who in turn rented it to a traveling carnival as a freak show exhibit. At one point, a group of infuriated old Civil War veterans threatened to hang the body. The body was passed around from one increasingly suspicious carnival to another, and was last seen in the late 1970s.

Bates continued to believe the Booth St. Helen George story until his death in 1923 at the age of 75.

He never met his granddaughter, who was born 25 years later — which meant missing the night in March 1991 when Kathy Bates won the Academy Award for Best Actress for her role as a creepy nurse in the hit movie “Misery.”

But in the end, no one questioned the authenticity of her Oscar statuette.