MENASource March 15, 2024 Print this page

Turkey and Egypt bury the hatchet, putting an end to the emerging Third Axis in the Middle East

Written by Borzou Daragahi

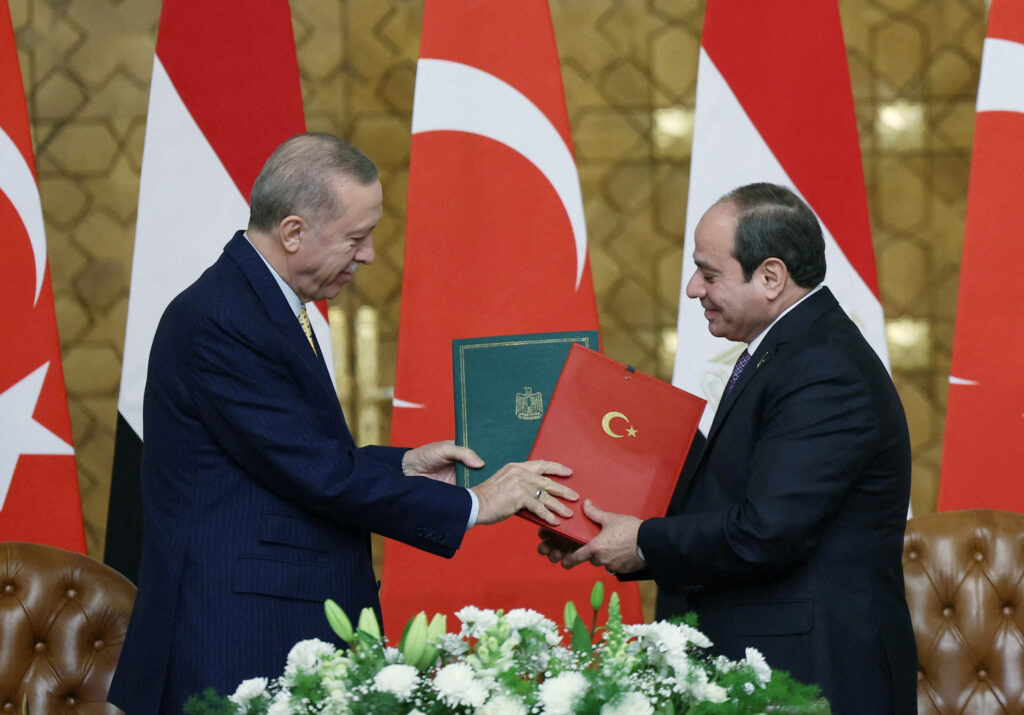

President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s visit to Egypt on February 14 marked a milestone in diplomatic relations between the two countries, which were bitterly at odds with each other during a rare period of nearly a decade of political and ideological differences. .

The carefully staged and well-worded meeting between Erdogan and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi also served as the final burial ceremony for the Middle East’s emerging Third Axis. This axis was different from the pro-Western Arab bloc led by Saudi Arabia, which included the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Morocco and Jordan, and the self-styled “Axis of Resistance” led by Iran. Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthis in Yemen, the Bashar al-Assad regime in Syria, and Shiite militias in Iraq.

That partnership consisted of Turkey, Qatar, and the Muslim Brotherhood and movements and parties in the Middle East and North Africa rooted in Sunni political populism, which peaked in the region after the 2011 Arab uprisings. Erdogan last visited Cairo in 2011, when pro-democracy and Islamist protesters were still celebrating the overthrow of longtime president Hosni Mubarak. I came to give a speech at the Arab League. In the aftermath of the Arab uprisings, Erdogan, then Turkey’s prime minister, was hailed as a “rock star” by Arab activists and Western thinkers as the country’s perceived model of moderate Islamic principles in a secular democracy.

Sign up for this week’s Middle East newsletter

At the time, Mr. Sisi was an unknown but powerful military official and a member of Egypt’s Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, which seized power after ousting Mr. Mubarak in 2011. He emerged from the shadows in 2013, removing and imprisoning democratically elected people. He will restore the dictatorial military regime of President Mohamed Mursi and Mubarak, with himself at the center of it.

President Erdogan considers Morsi a political comrade and has been at the forefront of condemning the coup. Turkey has welcomed Egyptians (mainly members of the Muslim Brotherhood and pro-Islamist dissidents fleeing Sisi’s purges and mass arrests), allowing activists to set up television stations and operate with relative freedom. did. Egyptian authorities abruptly canceled President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s planned visit to the Gaza Strip via the Sinai border. Diplomatic relations between Egypt and Turkey were downgraded in November 2013, just months after the coup.

Erdogan may have seen in Sisi the type of military dictator who has undermined Turkey’s democratic aspirations since the republic’s founding. The generals sent to the gallows one of Erdogan’s political idols, popularly elected Adnan Menderes, in 1961, and in 1997 they sent Prime Minister Necmetin Erbakan, Erdogan’s former political mentor, to the gallows. He was dismissed.

Relations between Turkey and Egypt have been strained for many years, with Egypt growing closer to Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which view the Muslim Brotherhood as a sworn enemy.

In 2017, Gulf states, with support from Egypt, launched an unprecedented blockade against Qatar, citing its geopolitical ambitions and support for populist Islamic groups. Turkey has supported Doha, airlifting emergency supplies as well as sending additional troops and expanding a security cooperation agreement signed by the two countries in 2014.

Tensions have been high since Sisi’s coup, but the blockade and its aftermath can be seen as indicating the emergence of a third axis.

Relations between Cairo and Ankara soured after Morsi died in prison in 2019. President Erdogan described Mr. Sisi as a “tyrant” and accused him of being directly involved in the death of the ousted president, who died of a heart attack while in court. “They were so cowardly that they couldn’t even hand over the body to the family,” Erdogan said. Meanwhile, Egyptian officials accused Turkey of supporting terrorist organizations.

The rift affected commerce. In 2017, Turkey’s exports to Egypt fell to $2.3 billion, the lowest level in 12 years, and in 2015, Egyptian exports to Turkey fell to $1.2 billion, the lowest level in 12 years.

Even more dangerously, Turkey and Egypt, along with their respective partners, have found themselves on opposite sides of armed conflicts and political struggles across the Middle East and North Africa. The Turkish government supported Syrian rebels, and Mr. Sisi sought to ease tensions with President Bashar al-Assad. Backed by then-US President Donald Trump, Turkey sought engagement with Iran even as Cairo’s partners Saudi Arabia and the UAE were at the forefront of the conflict with Iran.

But the Libyan civil war has become the most dangerous and decisive battleground between the Saudi-led Axis powers and the Turkish camp. Cairo and Abu Dhabi have sent weapons and fighters, including fighter jets and Russia’s Wagner forces, to warlord Khalifa Haftar’s Eastern Army, which launched an offensive on Tripoli in 2019. Turkey transported them openly, with possible financial support from Qatar. It sent weapons and military advisors to protect the Tripoli government, including elements from the Libyan branch of the Muslim Brotherhood. It was in Libya that Turkey first successfully deployed its now famous Bayraktar drone. They helped push back against Haftar’s forces in a full-scale proxy war that was costly and bloody.

As 2021 began, a deal brokered by Washington and Kuwait ended the blockade of Qatar. It made sense to end the dispute. First of all, Mr. Morsi is dead. The Muslim Brotherhood and its descendants were wiped out along with domestic political reform movements throughout the Arab world. Haftar’s high-stakes gamble has failed. Turkey has successfully entered the Arab world, establishing a semi-permanent military presence in the territories of the former Ottoman Empire, including Libya, Syria, Qatar, and Somalia.

In fact, there was nothing left to dispute.

Sisi, standing alongside Erdogan in February, said he welcomed the “current period of peace” in the region. “We hope that on this basis we can reach lasting solutions to unresolved conflicts,” he said.

Days after Erdoğan and Sisi’s meeting on February 14, Turkey revoked the Turkish citizenship of Mahmoud Hussein, the former leader of the Muslim Brotherhood, and 50 other members of the organization.

Continuing to hold grudges will hurt both countries. As tensions eased, trade recovered. Turkey’s exports to Egypt surged to $4.5 billion in 2021, an increase of 43% year-on-year, and reached $4.5 billion in 2022. Egypt’s exports to Turkey increased from $2 billion in 2018 to $2.6 billion in 2021, the highest in 10 years. In 2022, it will reach a record high of $3.7 billion.

Forging friendly relations with Egypt, along with ending the Muslim Brotherhood’s free reign in Turkey, could only provide access to a pool of liquidity in the midst of an economic crisis and the most formidable political challenge facing Erdoğan. It is also likely that it was necessary for friendly relations with the UAE and Saudi Arabia. During a public appearance in Egypt last month, President Erdogan said the two countries had committed to doubling their trade volume. He spoke about cooperation on defense and energy projects, including gas reserves in the eastern Mediterranean.

Detente between the two countries only really began in 2021, but likely would have begun sooner had it not been for the death of Morsi, which led to a sharp escalation of rhetoric between the two countries. In addition to economic interests and a regional shift toward a more multipolar diplomatic posture, Erdogan’s political ideology began to shift in 2015, when he abandoned hopes of courting devout Kurdish voters and the liberals who had once supported him, embracing instead the same hard-line nationalists that had tormented his ideological forebears for decades.

Egypt and Turkey came close to armed conflict in the late 1950s, when Gamal Abdel Nasser’s Arab nationalist movement tried to draw Syria into a tentative unification of Egypt and Iraq. But the recent rift between Egypt and Turkey is unusual: two militarist states obsessed for decades with territorial security and the consolidation of power for the privileged elite have clashed dramatically not over borders or resources, but over principled issues of national legitimacy, human rights, and political objectives.

Before addressing activists in Tahrir Square during his historic visit to Cairo in 2011, President Erdogan was scheduled to pay President Mubarak a big official visit. Perhaps it was to finalize some kind of agreement recently struck with President Sisi. President Erdoğan canceled the visit due to Mubarak’s response to ongoing protests in Tahrir Square. This is a testament to the far-reaching impact of the Arab uprisings.

“Hear the people’s cry. It is a very humanitarian demand. Do not hesitate to fulfill the people’s desire for change,” Erdoğan said.

The shaking from the 2011 earthquake stopped long ago. The region has settled into a more boring status quo, ruled by dictators who divvy up the spoils behind closed doors. Both Erdogan and Sisi have hinted at support for the Palestinian cause amid Israel’s attack on Gaza, but it is unlikely that the two countries will take bold steps in this regard. For now, relations between Turkey and Egypt will focus on expanding large-scale energy deals, tourist numbers and lucrative business ties.

Borzou Daragahi is a journalist who has covered the Middle East, North Africa, and Europe for news organizations in the United States and the United Kingdom since 2002. He is also a non-resident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Security Initiative. Follow him on X: @Borzo.

References

Photo: Turkish President Erdoğan and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah El-Sisi attend the signing ceremony on February 14, 2024 in Cairo, Egypt. Murat Cetinmukhdar/Turkish Presidential Press Office/Distribution via Reuters. Note to editors – This photo was provided by a third party. Resale or archiving is prohibited.