Have you ever worn oversized shoes or lost your golf ball in an artificially colored river? If so, you’ve probably played miniature golf or mini golf, one of the most popular sports of our time. You’ve probably played it before. The origins of this pastime are as debatable as the success of hitting a hole in one.

One thing that is not in dispute is the surprisingly destructive history of miniature golf. People on the fringes of the sport, who had been blocked from the golf course by gender, race, and class, actually brought golf to the masses and made it vibrant and fun. Learn more about how the sport has become so inclusive.

Women and the origins of miniature golf

The origins of mini golf are debatable. Some say the idea dates back to the private residences of elites in Europe and the United States, while others attribute the development of the game to its commercial birth in the 1920s. But there is one group he will always be essential to this sport. It’s a woman.

Women’s participation in golf is as old as golf itself, originating in Scotland in the Middle Ages and formalizing it in the 18th century. Women were also interested in the sport, but were largely prevented from participating due to the constraints of the era, which condemned active women as “unladylike” and incompetent. As historian Jane George writes, the presence of women on the golf course was “seen as a distraction to serious male golfers.” Prestigious golf clubs allowed women to participate, but they were relegated to fundraising, social events, and supporting male family members.

(Why women’s basketball is still fighting for equal recognition.)

Some claim that mini-golf originated at a ladies’ putting green called “The Himalaya” at St. Andrews Golf Course in Scotland. This small, uneven course had obstacles and was considered a better option for women to play golf in the absence of men.

Courtesy of St. Andrews University Library and Museum, ID: GMC-13-40-1

This gender discrimination frustrated women and even inspired one of the forerunners of miniature golf. At Scotland’s legendary St. Andrews Golf Course, women who were previously banned from the links have started playing on a caddie-only course. However, their husbands objected to their wives interacting with caddies, seeing them as socially inferior, so they specified other courses that were more “suitable” for the women. The course was so bumpy that it was known as the Himalayas. There, in 1867, around 100 women came together to form the St. Andrews Ladies Golf Club.

Designed by Scottish golf legend Old Tom Morris, this putting green featured nine holes and obstacles like streams and bridges. Wealthy women participated in lavish monthly cooking contests, competing for prizes such as opera glasses and rings. The small peak in the Himalayas, which is still open today, foreshadowed the coming putting boom and the role marginalized people would play in the development of the sport.

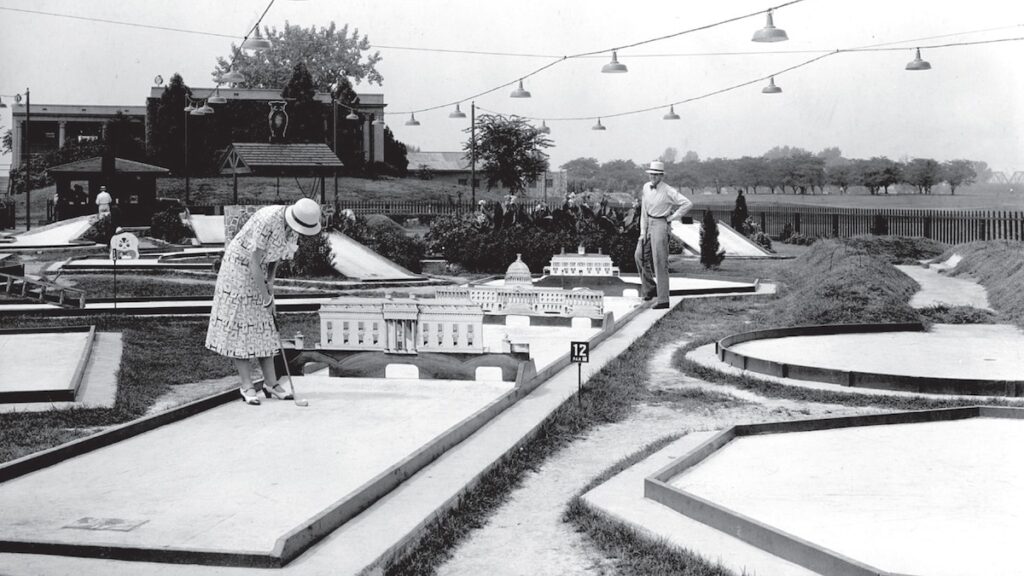

Women play golf at West Potomac Park in Washington, DC, circa 1930. The city’s first nine-hole golf course opened in 1920 as part of the city’s movement to democratize the sport, but initially only black residents of the city were allowed to play on the course for half a day each week.

Women play golf at West Potomac Park in Washington, DC, circa 1930. The city’s first nine-hole golf course opened in 1920 as part of the city’s movement to democratize the sport, but initially only black residents of the city were allowed to play on the course for half a day each week.

Photo courtesy of the Washington DC Historical Society

Mini golf for the masses

When golf spread from England to the United States, the first players were elite men, most of whom were members of exclusive Gilded Age gentlemen’s clubs. They established sporting clubs, the forerunners of country clubs, in their residential cities and summer resorts like Newport and Saratoga Springs.

(These mansion museums reveal the grittier side of the Gilded Age.)

While society’s elites rushed to separate their favorite sport from the masses, golf was infiltrating the mainstream, attracting people of all classes, races, and genders. Beginning with New York’s Van Cortlandt Park in 1895, cities began building municipal golf courses. As sports historian George B. Kirsch points out, after World War I, increased leisure time, suburbanization, consumerism, and prosperity “created a new wave of enthusiasm” for golf. By the 1920s, golf had become a national boom.

However, the popularity of golf has come with a problem of space. Traditional golf courses span up to 200 acres, land that is in short supply in many cities and even wealthy private estates. And it is that dilemma, many say, that led to the true origins of his game of miniature miniature golf, a sport that is more whimsical and more approachable than upper-class golfers expected.

British shipping magnate James Wells Barber inadvertently introduced the sport in 1917 by building a small 18-hole course, This’ll Do, on his property in Pinehurst, North Carolina. contributed to the popularization of a small-scale version of Mini courses featured natural and man-made obstacles, and a flourish of architecture and landscaping that would later influence miniature golf courses.

Meanwhile, Georgia hotel owner Garnet Carter was trying out her miniature golf game. Created by his wife Frieda and Carter in the mid-1920s, Mini Golf’s course design took the idea of the “miniature” to the extreme, incorporating small fairy-tale-themed architectural elements, gaudy statues, and neon lights. , and incorporated many fanciful decorations. Hazards such as hollow logs and bridges are watched over by gnome-like figures. This concept, with artificial greens made from cottonseed husks, was so popular that Carter patented it and the “Tom He Sam” golf course was born.

Garnet Carter putsts at the original Tom Thumb Miniature Golf Course in Lookout Mountain, Georgia. Carter and his wife Frieda invented these fanciful links filled with gnomes in the 1920s.

Photo courtesy of Picnooga, Chattanooga Public Library Paul A. Heiner Collection

Tom Thumb’s course differed from the greens frequented by wealthy golfers. The patented miniature course required only 2,100 square feet and could be installed indoors or outdoors. “Here is indeed a game of putting that will whet the appetite of the most experienced golfer and excite the fingertips of millions of Tom Thumb fans,” read a 1930 ad seeking investment in an indoor version of the game. It was ringing.

This was a big hit. Across the country, people began building themselves ever more luxurious mini golf courses. Soon, miniature golf could be found on rooftops and public parks, and by the end of the 1930s he had installed as many as 50,000 miniature attractions (often advertised as “midget golf”) across the United States.

The trend continued even as the United States fell into the Great Depression. As pop culture historian Nancy Hendricks explains, this cheap game is a way to “cure the depression of the Great Depression,” a way to imitate the rich, and even turn your small plot of land into increasingly outlandish courses. It was even seen as a way for people to make money.

Civil Rights in Mini Course

Mini golf has now become a legitimate national obsession. This little game didn’t just appeal to white Americans. This little game piqued the interest of black golfers, who had long been involved in the sport in the United States, first as slave caddies and then at segregated country clubs and some municipal courses. Historian Lane Demas points out that in 1930, many of New York City’s 150 mini-golf courses were located in Harlem, and many were affiliated with legendary venues such as the Apollo Theater and the Savoy. There is. “Nearly every black enclave in the North experienced a miniature golf craze,” Demas wrote.

Mini golf also became popular in the Jim Crow South. Excluded from white-owned country clubs, many serious black golfers could only practice at white-owned mini-golf facilities. In response, black community organizations built their own mini-golf courses.

(Remains of racism still haunt public swimming pools.)

On June 29, 1941, three black golfers, Asa Williams, George Williams, and Seal R. Showell, walked onto the East Potomac Park Golf Course to protest the segregation of public recreation areas in Washington, D.C. Ta. Their protest would lead to the elimination of racial discrimination. All municipal golf courses in the district.

Photo courtesy of Washington National Records Center

Golf also played a groundbreaking role in the desegregation of the capital’s public recreation areas. The mini-course was one of the first to be desegregated. By 1941, black golfers were already pushing for and acquiring municipal golf courses in the District of Columbia, but the grounds were neglected and inferior to those of white golfers. That summer, a group of black men tried to play at the segregated East Potomac Park municipal golf course in protest, only to be yelled at by white golfers.

As a result of this incident, Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes desegregated parks, including miniature golf courses, for the first time in the Jim Crow era. Ike also vowed to consolidate all federally funded golf courses in the area. It took him more than a decade for Washington, D.C., to integrate all its public entertainment facilities, but this protest was a first in history for black golfers.

Other miniature golf courses also played a role in the history of the civil rights movement. For example, the municipal mini-golf course in St. Augustine, Florida became the city’s first public venue open to blacks in 1964.

Since then, the sport has had its ups and downs. His car-crazed 1950s ushered in a new golden age for this fanciful sport, but it faced a long decline with the end of the 20th century.

Nevertheless, miniature golf and its destructive spirit continue to entertain amateur and professional golfers alike. And mini golf continues to appeal to a wide range of people. The National Golf Foundation estimates that in 2022 alone, 18 million people played mini golf, 45 percent of whom were women and 24 percent of whom were non-white.