Nearly two years later, we can finally all agree that the Supreme Court’s new, sweeping “history and tradition” standard for important cases has accomplished two things: it has delivered a major victory for conservative policy and created chaos for lawmakers and judges across the country.

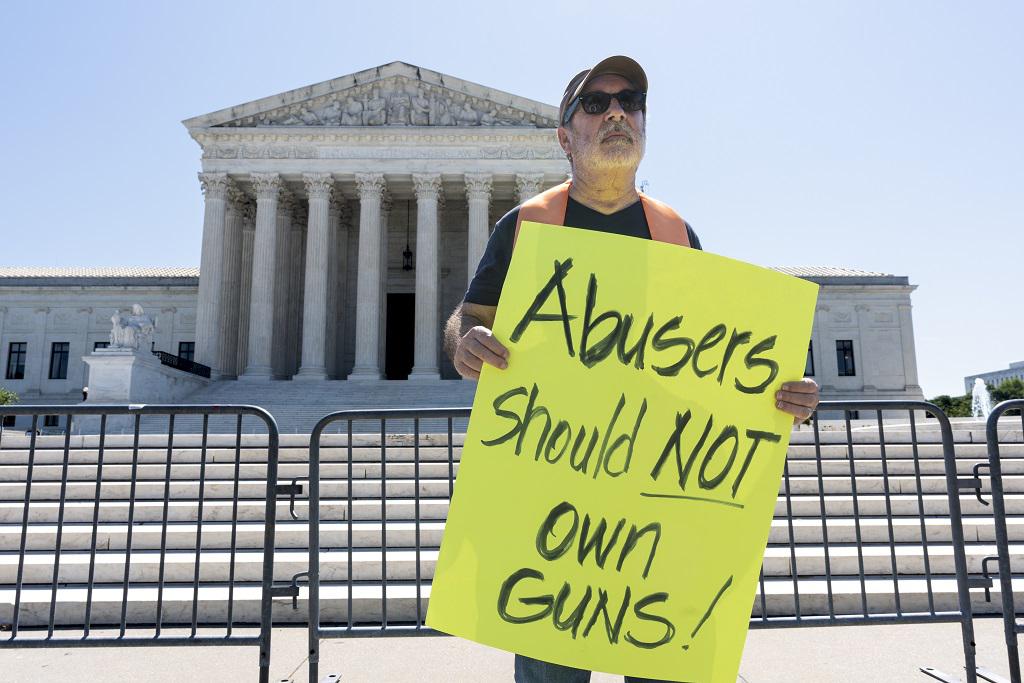

The Supreme Court today upheld a law allowing people to temporarily disarm those who have domestic violence restraining orders in place, rejecting Justice Clarence Thomas’ absolutist view of the Second Amendment and also revising the “history and tradition” test that conservative justices devised in 2022.

This ruling is perhaps the most important decision in an unexpectedly quiet week for the Supreme Court, which still considers important issues such as presidential immunity, social media regulation, homelessness, and the scope of government agency power. It is also a small victory for American society, especially women, because, as some liberal justices pointed out in their ruling, women are five times more likely to be killed if their domestic abuser has a gun.

More articles by Hassan Ali Kanu

The issue of guns for people under restraining orders came to the Supreme Court in the first place because of the conservative majority’s decision in New York State Rifle and Pistol Association v. Bruen, which significantly expanded gun rights. Bruen was one of three shocking decisions in June 2022, including Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned a woman’s constitutional right to an abortion, and another that blurred the thinning line between church and state.

Both of these decisions replaced decades of precedent that applied to specific situations with a one-size-fits-all “history and tradition” test. This test instructs courts to determine whether a law is constitutional simply by looking at “historical practice and understanding,” without further guidance. Prior to June 2022, courts used situation-specific analyses designed to weigh the purpose — the government’s goal — against the means or methods the government chose to achieve it.

The “history and tradition” test essentially tells judges and legislators to look at 18th and 19th century history, turn them into professional historians, and see if there were laws or policies that supported their legal claims (i.e. cherry-pick). Their decisions and newly enacted laws can eventually be challenged all the way to the Supreme Court, which will decide whether the lower courts properly looked at history. Sounds perfect, right?

An unusually large number of judges have publicly complained about the test, both in and out of their own opinions.

The test has been criticized from the beginning, including for the fact that it is always applied when the Supreme Court changes the law, and that it almost always seems to be applied to enact conservative or right-wing policies. (I am one of the critics.) Lawyers and scholars have said the test is a “memory game” that is inconsistent, misguided, unworkable, and exclusionary. In fact, long before 2022, practicing historians sometimes called such “legal analysis” “law firm history,” and not in a good way.

An unusual number of judges have also publicly complained about the test, both in and out of opinions. U.S. District Judge Carlton Reeves wrote in a 2022 ruling:[w]”We are not experts on what white, wealthy, male landowners thought about gun control in 1791,” he said, reiterating that even if one acknowledged that this was a sensible approach, judges cannot do the work of trained historians. Judge Kevin Newsom of the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals, an appointee of President Donald Trump, criticized the test in a speech at Harvard Law School in February.

Today’s gun rights decision illustrates the problem: The 8-1 decision made Bruen’s position clear, but six justices decided in separate concurring opinions that they wanted to say something different or even more.

This test, or an updated version of it, is much looser than lower courts had considered, the justices said: it requires only historical parallels that are consistent with Second Amendment principles, not historical laws that are “look-alikes” or “historical twins” of modern laws.

Each of the three liberal justices added that Bruenn was wrong and that they were troubled by the “history and tradition” test. And nearly all the justices except Bruenn’s author, Clarence Thomas, agreed, at least in the majority opinion (written by Chief Justice John Roberts), that “some courts have misunderstood the methodology” of the tradition test.

So we all agreed that the “history and tradition” test, at least initially, was not particularly clear.

In a way, this is an acknowledgment of some of the criticisms of the test, as Justice Jackson, who was not on the Supreme Court when Bruen was handed down, certainly seemed to think.

“Please don’t get me wrong. Today’s efforts to clear up “misunderstandings” are[andings]”This is a tacit admission that the lower courts are struggling. In my view, the blame may lie with us, not with the lower courts,” Jackson wrote.

This seems like a very fair point, especially considering that before the invention of the “history and tradition” test, judges hadn’t openly complained in conferences or written reams of decisions saying they had no qualms about the validity of the analysis at all. We hadn’t wondered whether we could take guns away from perpetrators of domestic violence, no federal court had ruled that state judges could offer prayers in court, and no lawmakers had enacted laws requiring the Ten Commandments to be posted in public schools.

One justice agrees that the blame for all this may lie with the conservative wing of the Supreme Court and their new legal test that seems to produce nothing but chaos and right-wing policy victories. But we can all agree that the test is at least a little confusing.