In the 19th century, Manhattan’s busy streets had a horse problem: an estimated 150,000 horses roamed the city, producing 22 pounds of waste per animal per day.

On March 27, 1897, a motorized taxi service launched in New York City, promising a cleaner solution: Gotham’s first taxis were powered by electricity rather than gasoline. In fact, the car of the future was a thing of the past.

Electric start

The idea of electric cars cruising around New York City in the 1890s may have sounded like a steampunk fever dream, but as the automobile age dawned, battery-powered cars outsold their internal combustion-engine counterparts. Electric cars were quiet, clean, and easy to drive. “Back then, you were lucky if your gasoline-powered car would start in the morning,” says Dan Albert, author of Are We There Yet? The American Automobile Past, Present, and Driverless. “Gasoline-powered cars were loud, polluting, and clunky; electric cars started with the flip of a switch.”

When electricity first started to be used in the 19th century, it seemed as if it could overcome any challenge. “If you asked anyone on the street what was going to happen next, they would say electricity was a magical force,” says David A. Kirsch, an electric car historian and author of The Electric Car and the Burden of History. “We used electricity for lighting. We used electricity to traction streetcars. Electricity was everywhere, and now it’s what gets us transported.”

Pioneering Electrobat

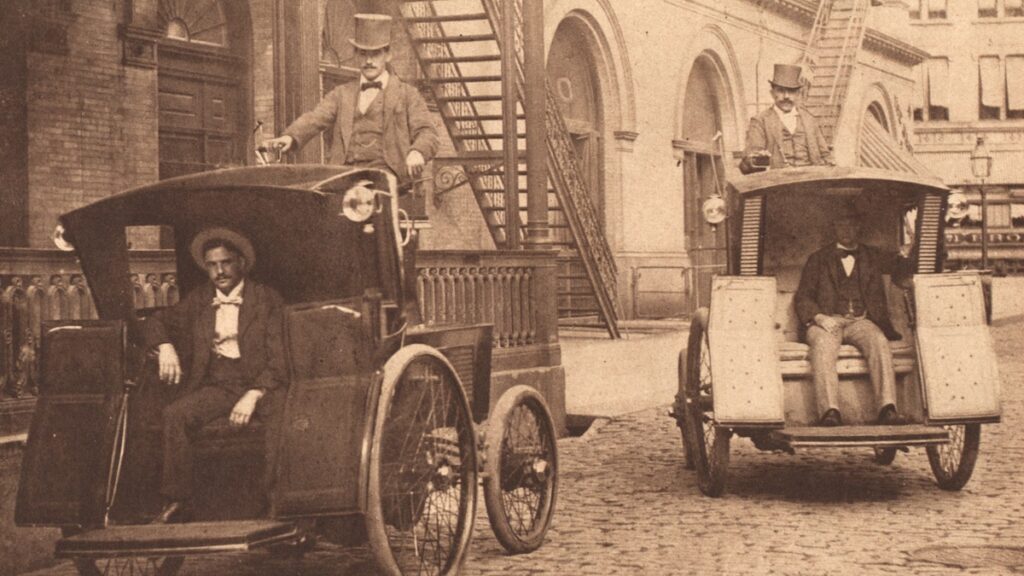

Back when Nikola Tesla was the only Tesla in the spotlight, the Electrobat emerged as the first commercially viable electric car. Built in 1894 by Philadelphia engineers Henry Morris and Pedro Salom, the 2,500-pound vehicle was powered by lead-acid batteries and could reach a top speed of 15 mph and travel up to 25 miles on a single charge.

The two also devised an ingenious battery-swap system at an old roller skating rink on Broadway to keep the cab running. With the efficiency of a NASCAR pit crew, workers used elevators and hydraulics like an overhead crane to maneuver the car, remove the 1,000-pound depleted battery, and insert a new one, a process that took just three minutes. “It was a lot faster than swapping out a team of horses and probably as fast as filling up a gas tank today,” Kirsch says.

Their Manhattan taxi service quickly became popular, especially among the upper class, and instead of selling their cars, Morris and Salom decided to lease them by the month or per ride through their own venture, the Electric Wagon and Carriage Company.

The taxi fleet grew significantly, from just 12 in 1897 to over 100 by 1899. The Electrobat proved to be an ideal city car, with its quick acceleration and quiet ride. But its speed and quietness brought unexpected challenges. In May 1899, taxi driver Jacob Jarman was reported to be speeding down Lexington Avenue at 12 miles per hour, becoming the first motorist to be arrested for speeding. A few weeks later, an electric taxi struck and killed real estate broker Henry Bliss as he got off a streetcar on the Upper West Side. The first pedestrian to be killed by a motor vehicle had not heard the Electrobat.

The bubble bursts

Morris and Salom received new backing from wealthy investors, notably William Whitney, known for his success in electrifying New York’s streetcars. Under Whitney’s direction, the company merged with electric streetcar and battery manufacturers to form an integrated national electric transportation network.

The Electric Vehicle Company quickly expanded its taxi business to major cities like Philadelphia, Chicago, and Boston, eventually becoming the largest automobile manufacturer in the United States. But the rapid expansion proved unsustainable: operations outside of New York were poorly run, and when a New York Herald investigation in late 1899 revealed that the Electric Vehicle Company had received fraudulent loans, investors felt cheated. The company’s stock price plummeted, and by 1902 the company was effectively bankrupt.

Electric cars lose power

The company’s collapse shocked the investment community and cast a dark cloud over the future of electric vehicles.

“It wasn’t the idea, the technology or the business model that killed it,” Albert says, “it was the shady politics behind it.”

A devastating fire destroyed much of the fleet, which, combined with the economic turmoil of the Panic of 1907, dealt a final blow to electric taxis in New York City, where gasoline-powered cars were gaining traction in the market. That same year, local businessman Harry Allen started a taxi service with 65 gasoline-powered taxis imported from France. Within a year, his fleet had swelled to 700 vehicles.

While the internal combustion engine will likely power America into the next century, battery power is slowly making a comeback after a long detour. The future of the car has arrived again when 25 all-electric taxis begin operating on New York City streets in 2022.