Because bacteria can easily hibernate in low-moisture ingredients like flour and spices, food scientists are researching ways to make them safer using new techniques.

The publication of food safety studies on radio frequency pasteurization and new steam technology highlights the recent nationwide recall of black pepper due to the risk of Salmonella infection. The June 3 recall brought low-moisture foods to the forefront of public discussion, demonstrating that just because bacteria cannot grow well in dry foods doesn’t mean it doesn’t pose a threat.

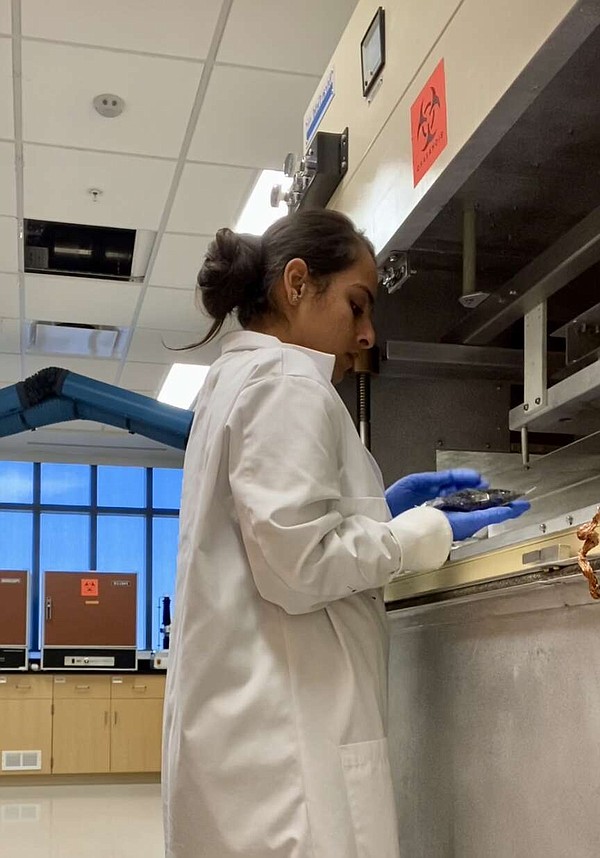

Surabhi Wason is lead author of the study titled, “Radio-frequency inactivation of Salmonella in black pepper and dried basil leaves by in-package steaming treatment,” which was published in the Food Protection Journal.

She developed an in-package steaming process to increase the efficiency of radio frequency pasteurization of spices and conducted experiments to evaluate its impact on spice quality.

“Radio frequency, also known as microwave, is a long wavelength, non-ionizing electrical energy,” says Wason. “An important application area for radio frequency technology is in the processing of dry raw materials, where microorganisms lie dormant and may be most difficult to kill.”

Wasson explained that a radio frequency (RF) generator creates an alternating electric field between two electrodes, which creates friction on the polar water molecules in the material, heating it rapidly and uniformly.

Wasson is a former doctoral student of study corresponding author Jeyam Subbiah, head of the food science department, which is part of both the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station, a research arm of the University of Arkansas System Division of Agriculture, and the Dale Bumpers College of Agriculture, Food and Life Sciences.

Rossana Villa Rojas, assistant professor of practice in the Department of Food Science and Technology at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, is co-author of a study showing that radiofrequency pasteurization and a new steam technology can inactivate Salmonella in low-moisture foods, including spices, without significantly compromising quality.

The findings are based on work funded by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Grant Number 2020-67017-33256. McCormick & Company provided low-moisture food ingredients for this study.

How to use

If salmonella is detected during product quality testing or in the event of a food poisoning outbreak, the industry must recall all products since the plant’s last cleaning, Subia explained.

“Food processing plants that process low moisture foods are cleaned less frequently, usually once a year, as moisture in the plant can pose a food safety risk,” says Subbiah. “This means that the industry has to recall days to months’ worth of produce, potentially recalling the entire product on the shelves, as well as thousands of other products that use it as an ingredient, which is a huge economic loss. People don’t understand the importance of food safety.”

Traditionally, foods with low moisture content must be exposed to high temperatures for long periods of time to kill bacteria. Subia says that harsh treatments are necessary to kill pathogens such as Salmonella and Listeria because they have adapted to harsh environments and can remain hidden for years. Without inactivation treatments, the pathogens can begin to grow when they encounter ideal conditions, such as when spices react with water when used in soup.

Powdered milk is also a low-moisture food that can be dangerous when rehydrated, and Subia said contamination with Cronobacter sakazakii in powdered milk could lead to severe illness or death in infants.

Subia said that with traditional methods, excessive heat treatment can reduce food quality, such as nutrients, and steam generation can damage packaging. Scientists can also pasteurize these foods by irradiating them, but consumer acceptance is low, he added.

Subia wondered whether packaging techniques commonly used for foods such as vegetables cooked in a microwave could be adapted to heat dry foods just as quickly, with the added step of resealing before sale. To prevent steam building up and eventually bursting the package, experts developed a one-way valve that releases steam and reseals. This is the crux of Subia’s research.

This new valve technology mimics in-package sterilization of canned goods and uses radio frequency heating. With traditional heating methods, heat travels from the surface of the product and takes time to reach the center, but radio frequency heating, like microwave technology, generates heat evenly throughout the product through friction caused by water molecules vibrating in an electric field. This method ensures that the product is pasteurized while still in its final package and heated evenly, avoiding the risk of overheating the edges before the heat reaches the center. This in-package process reduces the risk of contamination that can occur as the product moves between the pasteurization and packaging stages, and the food is safe from contamination until the customer opens it.

“The best way is to package it in its final form, like a can, to kill any bacteria,” Subia said.

“The technology can also be applied to other products such as flour and grains, demonstrating its potential to provide a powerful solution for various food sectors,” Wason added. “Furthermore, one of the key advantages of radio frequency sterilization is its continuous processing capability. By implementing a conveyor belt system, products can move seamlessly through the RF chamber, ensuring consistent and efficient sterilization.”

A sticky situation

Sabia first began researching the topic of low-moisture food safety after witnessing the costs of the 2007 peanut butter recall.

A recall for a product such as packaged meat requires consumers to avoid products processed on a particular date. But for dry foods such as peanut butter, production facilities may only sanitation once a year or once every few years to avoid exposing the product to water. This means that in the event of a recall, a year’s worth of the product, and other foods made from it, could pose a risk to consumer health and financial losses to producers.

The company ended up recalling all of its peanut butter produced back to January 2004, and estimates it will lose between $50 and $60 million.

In addition to working at the experimental station, Subbiah also collaborates with the Michigan State University-based Center for Low Moisture Food Safety, which includes a stakeholder advisory group of industry experts who take research like Subbiah’s from publication to the real-world application stage.

For more information about the agriculture sector’s research, visit the Arkansas Agricultural Experiment Station website at https://aaes.uada.edu

Maddie Johnson is with the University of Arkansas System College of Agriculture.