This working paper is a product of Carnegie’s Turkey and the World Initiative.

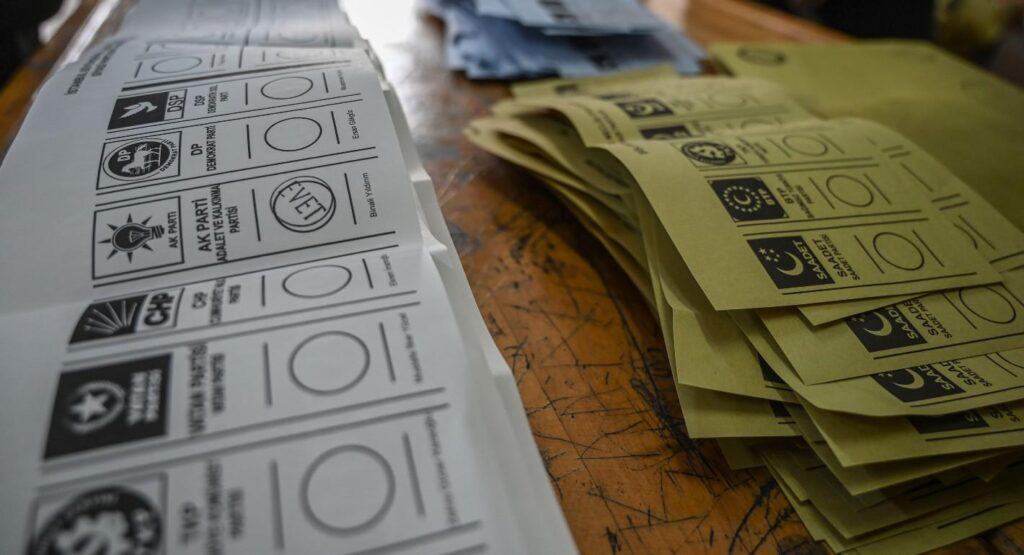

Turkey is heading toward a set of twin elections that could have momentous consequences for the country’s future. In June 2023 at the latest, Turkish voters will be asked to choose a new president and a new parliamentary majority. For the past two decades, the Turkish political landscape has been dominated by the Justice and Development (AK) Party and its uniquely successful leader, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. After having ruled the country single-handedly since 2002, Erdoğan became the first executive president of Turkey in 2018, following a tightly contested constitutional change. He has come out victorious in every round of elections since the start of his political career. And yet, after two decades, his popularity is faltering, raising the prospect of political change.

The turning point for Turkey’s political system has been the transition to a presidential system with the constitutional amendment of 2017.1 Since the start of multiparty elections in 1946, Turkey had had a parliamentary system, and since 2002 it has had single-party governments. With Erdoğan at the helm, the AK Party has won nearly all elections over the past two decades. It only failed to win a parliamentary majority in the most recent elections,2 in June 2018, and since then has been forced to rely on the support of the hyper-nationalist Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) to secure control of the legislature.3

The transition to the presidential system forced a realignment of the political constellation. The structural impact of this transition has led to the creation of two major political alliances. The Cumhur, or People’s, Alliance is led by the AK Party and includes the MHP and a small number of marginal parties. The Millet, or Nation, Alliance is led by the main opposition, the center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP); it also includes the center-right/nationalist İYİ Party as well as the Saadet and Demokrat parties, which appeal to a smaller electoral base.

The first real test of this alliance-based politics was the municipal elections of March 2019, where the opposition alliance performed markedly better. Millet-backed opposition candidates won the electoral race in nine out of Turkey’s ten major metropolitan cities, including Ankara and Istanbul. These cities had been ruled by mayors linked to the AK Party and its predecessors since 1994.

Now the alliances are gearing up to contest the critical 2023 elections. The ruling Cumhur Alliance’s candidate will be Erdoğan, who will try to win a third term as Turkey’s president. The candidate of the Millet Alliance is still unknown. Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, as the leader of the main opposition party, is intent on becoming the Millet candidate, but there are doubts about his electability against Erdoğan. Meral Akşener, the chairwoman of İYİ—the second-largest opposition party—has so far sidelined herself from the presidential race. Ekrem Imamoğlu, the mayor of Istanbul, and Mansur Yavaş, the mayor of Ankara, are also possible presidential candidates for the opposition. At present, all four potential candidates for the opposition are polling better than Erdoğan—fueling speculation about political change.

According to the August 2022 survey of polling company Metropoll, Erdoğan has fallen behind all the major and potential candidates of the opposition. With Yavaş as the leading contender, the gap is around sixteen points. Even with Kılıçdaroğlu, the least popular but possibly most likely potential candidate of the opposition, the gap is more than six points.

A similar picture is emerging in the parliamentary race. According to the September 2022 survey of Türkiye Raporu, support for the AK Party is at the historic low of 22.2 percent (excluding undecided voters). The CHP is second with a support level of 20.5 percent. After the undecided voters are accounted for, the AK Party vote rises to 29.7 percent, with the CHP at 27.2 percent and the İYİ Party at 16.7 percent. The AK Party’s parliamentary ally, the MHP, is at 7.4 percent.

Aside from specific candidates, general political trends also look ominous for the ruling party. The AK Party–led People’s Alliance has been steadily losing ground against the CHP–İYİ Party Nation Alliance. Support for the People’s Alliance dropped to 27.6 percent in June 2022 from 43 percent in November 2019. The Nation Alliance was calculated to be ahead by four points at 32.3 percent. But the gap is in reality much wider, as the pro-Kurdish Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), which is polling at 8.8 percent is also likely to support the opposition candidate in the presidential election.

The economy is the primary reason for the widespread disenchantment with the ruling party and Erdoğan. The Turkish economy is under duress; consumer inflation has reached 80 percent.4 Unanchored inflation undermines the standard of living of ordinary citizens. Perceptions about the state of the economy, as illustrated by the polling of Türkiye Raporu, have consequently worsened to unprecedented levels, with 53 percent of the population stating that the economy was “bad” or “very bad.”

Expectations for the outcome of the 2023 elections are taking form against this political and economic backdrop. A potential leadership and government change would have major ramifications for Turkey and its foreign policy after two decades of AK Party rule.

This analysis aims to shed some light on Turkey’s postelection foreign policy orientation in the event of political change and provide insights on how a non–AK Party government and leader in Turkey would reshape the country’s foreign policy. A major difficulty in this respect is the prevailing uncertainty over the presidential candidate of the opposition alliance and the setup of the postelectoral Parliament. The main opposition parties will seek to maintain their alliance to contest the parliamentary race, possibly extending it to others, like the Democracy and Progress Party (DEVA) (headed by the former economics and foreign minister Ali Babacan) and the Gelecek Party (headed by the former prime minister and foreign minister Ahmet Davutoğlu). And yet given that no single party is likely to obtain a majority in Parliament, the opposition will need to establish a postelectoral coalition. As a result, this inevitably premature analysis of Turkey’s future governance envisages a complicated political setup should there be political change after the elections, with an executive president and a Parliament ruled most likely by the political coalition of the CHP and the İYİ Party, given their much stronger voter base.

Our adopted methodology has been to interview the foreign policy spokespeople of the opposition parties—the CHP, the İYİ Party, DEVA, Gelecek, and the HDP—enabling a comparative analysis of their approaches on specific topics and a contrast of their policy preferences with those of the AK Party.5 The topics addressed are relevant not only for Turkey, but also for the region and beyond. This paper will summarize our findings and help illuminate the foreign policy agendas and priorities of the different parties composing Turkey’s political opposition, which should in turn provide a better understanding of the dynamics that shape Turkish foreign policy. The first section reflects the main critical points raised by the interviewees on the AK Party–led foreign policy of the last two decades. The following sections are categorized under specific themes and cover the commentary and recommendations of the opposition on Turkey’s relations with the United States, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), the European Union (EU), and Greece, as well as with non-Western actors like Russia and China. Also included are their policy proposals on major issues like the Eastern Mediterranean, Cyprus, Syria, and refugees. The final section provides a critical analysis underscoring the limits of our adopted approach of seeking to draw conclusions on the future of Turkish foreign policy at a time when uncertainties remain, not only about the postelection political leadership of the country but also about the cohesiveness of future policymaking.

Opposition Parties’ General Outlook on Foreign Policy

With the exception of the İYİ Party, the political opposition opted to analyze the evolution of Turkey’s foreign policy under the AK Party in two separate eras, with the first period covering approximately the first decade of AK Party rule. For the CHP’s Ünal Çeviköz, the real success in that initial period was ensuring the continuity of Turkey’s traditional foreign policy proclivities. According to Çeviköz, the AK Party seized the EU membership objective and implemented a host of domestic reforms that ultimately resulted in the start of membership negotiations in 2005.6 In another sign of growing prestige, Turkey was elected as a nonpermanent member of the United Nations (UN) Security Council with a record number of votes in 2009.7 The start of Turkey’s outreach to Africa also dates back to that period. These achievements should be seen as successes for Turkey’s foreign policy.

DEVA’s Yasemin Bilgel highlighted Turkey’s status in that period as a reliable, predictable, and influential regional actor, referring for instance to Ankara’s active role in mediation between Syria and Israel. She also recalled the positive Turkey-EU dynamic illustrated by the vote in the European Parliament in 2004, when many members took part in the session with signs saying “Yes” to Turkey’s membership.

For Ümit Yardım from Gelecek, the adoption of a less Western-centric understanding of the world and Turkey’s neighborhood constituted a major, lasting, and positive change in Turkish foreign policy. This paradigm shift, Yardım said, has allowed Turkish diplomacy to foster a better understanding of its region, especially the Middle East, the Balkans, and the Caucasus.

The turning point for Turkey’s foreign policy according to the CHP’s Çeviköz was the Davos moment in 2009,8 when Erdoğan clashed with Israeli President Shimon Peres at the World Economic Forum Summit. This dispute provided the backdrop to the Mavi Marmara incident in 2010,9 when Israeli Defense Force commandos boarded a Turkish flagship on its way to Gaza; the intervention led to several casualties and the downgrading of bilateral ties. Then came the Arab Spring, where according to Çeviköz the AK Party leadership believed with overconfidence that Turkey could be the winner of the unraveling regional order. Ankara totally reoriented its foreign policy principles by backing Muslim Brotherhood–linked political movements in the region in a radical departure from the established tenets of Turkey’s republican-era foreign policy.

The interviewees from Gelecek, DEVA, and the HDP believe, like Çeviköz, that the initial years of AK Party rule were a successful period for Turkish policy. For them the real turning point is the onset of the Arab Spring.

The criticisms of the different political opposition parties regarding Turkey’s foreign policy under the AK Party share many commonalities and can be categorized under the following headings.

A Policy of Interference

A fundamental criticism has been that Turkey’s foreign activism turned into interference in the domestic affairs of other nations. The observation is that starting with the onset of the Arab Spring, Turkish foreign policy has departed from its decades-long practice of noninterference. For Ahmet Erozan from İYİ, the clearest example is Syria, where Turkey not only championed regime change in a neighboring country but also got involved in organizing and supporting the political and military opposition to Damascus.10 A very similar viewpoint is offered by Bilgel from DEVA and Hişyar Özsoy from the HDP.

For the CHP’s Çeviköz, the departure from the principle of noninterference was coupled with double standards in the practice of diplomacy. He remarked that the AK Party leadership has often cited the protection of human rights at a global scale as a priority for Turkish foreign policy. But in practice, Turkey exclusively focused on the plight of one religious or sectarian group. Another example he gave was Turkey’s engagement with Tripoli on the grounds that it is the UN-recognized government while adopting the opposite view in Syria.

Çeviköz argued that the protection of human rights should in fact be an integral part of Turkey’s foreign policy, which the norms of international law should essentially guide. For him, a foreign policy agenda prioritizing the protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms on a global scale did not constitute a vehicle for interference. As long as there is transparency about the will to integrate the protection of human rights into the scope of Turkish foreign policy, Turkey can advance this agenda without necessarily harming its bilateral relations with countries that fail to uphold these norms. He indicated that, for instance, the CHP would have been much more critical of the treatment of the Uyghur minority in China. He added that this criticism stems from their belief in the universal nature of human rights as well as the need to ensure consistency in foreign policy and eradicate double standards.

Ideological and Partisan Foreign Policy

The opposition claimed the AK Party–led Turkish foreign policy had turned partisan, and that Turkey took sides in the internal political divisions of other countries. The aim may have been to elevate Turkey’s regional influence, but it backfired. According to Çeviköz from the CHP, Turkey should not take sides in regional disputes and should not espouse an ideology-driven foreign policy that is often perceived also to have a sectarian dimension. On the contrary, given Turkey’s geography, which is the epicenter of many conflicts old and new, Ankara should be in a position to reach out to all the relevant parties to a dispute. For instance, he remarked that in previous decades Turkey was an influential actor in the Arab-Israeli conflict and was in a position to defend more effectively the rights of the victimized Arab peoples, especially the Palestinians. He argued that Turkey lost this capacity with the rupture of its political relations with Israel. The HDP’s Özsoy also advanced the same argument.

Erozan from the İYİ Party stated that the leadership had striven to create a cross-national and regional political platform akin to the Socialist International, guided by the AK Party, based on religious values and closely associated with the regional affiliates of the Muslim Brotherhood. It included the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood, the Justice and Development Party in Morocco, the Justice and Construction Party in Libya, and the Ennahda in Tunisia. He added that the AK Party’s concept of establishing a regional hegemony through links with Islamist parties proved detrimental to Turkish foreign policy.

In the words of Erozan, the AK Party’s nonsecular foreign policy enterprise has also been the source of rekindled Islamophobia in the West. Perversely, it led Western countries (particularly France and Germany) to try to nurture their own version of Islam; this has even occurred to an extent in China. He maintained that the MHP also bore responsibility for this reaction because it championed a version of aggressive nationalism led by Grey Wolves–affiliated movements in Western Europe. According to Erozan, the ideological approach has been detrimental to the Turkish diaspora’s cohesion by creating divisions just as severe as those within Turkey. A clear example is seen in Bulgaria, where the AK Party supported the pro–AK Party diaspora to establish their own political party, splitting the Turkish vote.

De-institutionalization and Populism

Another common claim has been the erosion of the role of institutions. Since the transition to a hyper-centralized presidential system in 2017, decisionmaking has been concentrated in the presidency with little scope for other state institutions, including line ministries, to influence policymaking.11 This structural change has also affected the conduct of foreign policy. Erozan from the İYİ Party stated, for instance, that the Foreign Ministry can no longer act as a counterweight in the decisionmaking process and cannot correct the mistakes of the presidency. Yardım from Gelecek also highlighted the dysfunctionality of the presidential system. He indicated that previously, under the parliamentary system, the political opposition had more input regarding the conduct of foreign policy. Since the transition to the presidential system, the political opposition has been excluded from these deliberations and the role of the Foreign Ministry has been greatly eroded. This criticism was echoed in similar words by the HDP’s Özsoy. Yardım also remarked that the responsibility of the Foreign Ministry is now limited to its role as the implementing body of decisions shaped in a top-down policy environment devoid of interagency consultations. Bilgel from DEVA indicated that the transition to the presidential system had accentuated the shift from institutional to personal decisionmaking. As a result, she said, today there is no strategic, long-term decisionmaking on foreign policy; instead, there are daily reactions and tactical decisions.

Under this rubric, opposition party representatives also highlighted the need for Turkey to be more consistent in its public messaging and actions on related matters. They spoke of contradictions in statements among Turkish officials, as well as of occasional actions that seemed to clash with stated policies. This was mostly attributed to Turkey’s ill-functioning presidential system, which was believed to have relegated the Foreign Ministry to a subsidiary role in formulating and implementing foreign policy, leading to these problems.

A related criticism from the opposition parties has been that domestic politics have increasingly shaped foreign policy under the AK Party. In the words of the CHP’s Çeviköz, it is understandable for domestic concerns to influence foreign policy. But foreign policy should not be instrumentalized for domestic purposes, and it should not be used to create a false narrative of success to turn the attention away from domestic problems. For Gelecek’s Yardım, Turkish foreign policy has been undermined by populism in recent years with statements and postures that essentially vie to consolidate the support of domestic constituencies.

Loss of Strategic Orientation and Realism

Another shared criticism was that Turkey’s foreign policy had swerved too much in the direction of transactionalism. Some decisions, like the S-400 missile system purchase from Russia, have raised suspicions about Turkey’s strategic orientation abroad. For instance, Çeviköz from the CHP said that it is not wrong for Turkey to seek to have a balanced foreign policy. He remarked that for a long time, Turkey was able to nurture good relations with Russia while being a NATO member. Even during the Cold War, this stance never led to the questioning of Turkey’s status within NATO. But he says the AK Party has been inept at implementing a balanced foreign policy. Ankara and its foreign policy malpractice have caused suspicions about Turkey’s strategic direction.

The HDP’s Özsoy also remarked that Turkish foreign policy no longer had a strategic compass. He said that the situation was clear a decade ago, with Turkey aspiring to become an EU member and to advance in that direction with political and economic reforms at home. Today, especially after the Arab Spring, it is not possible to speak with confidence about Turkey’s strategic priorities under the current AK Party leadership. Transactionalism has come to define Turkey’s foreign policy instead of transformational long-term alliances.

Similarly, the İYİ Party’s Erozan emphasized his concerns over the militarization of Turkish foreign policy. While indicating that hard power could indeed be used as an instrument of foreign policy and that, in the past, Turkey had successfully relied on hard power (for instance, in 1999, when Ankara put pressure on Damascus to capture Abdullah Öcalan), Erozan maintained that hard power and by extension the Turkish military should be used more as a tool of deterrence. That is when the combination of hard power and foreign policy tends to be more successful, he said.

A related major criticism has been the delinking of foreign policy from realism. According to Erozan, a country may wish to uphold several objectives, but foreign policy objectives need to be compatible with the capabilities of a country. As a result, without clearly set priorities, foreign policy activism can be severely problematic. In the words of Erozan, that is exactly what has happened under the guidance of Erdoğan. The Syria policy is an egregious example. The government has established regions under its own control in Syria. But the exit strategy is unclear. In other words, what are the conditions under which Turkey will cease its presence there? For DEVA’s Bilgel, too, the growing gap between Turkey’s aspirations and its capabilities should be a major concern. She argued that based on this misguided approach, Turkey received many more refugees than it had capacity to absorb.

Relations With the United States

While foreign policy is not a leading consideration in the eyes of the Turkish electorate, and especially not so during times of economic hardship, relations with the United States are always a fraught topic. This has intensified as Turkish-U.S. relations have deteriorated in recent years, and the Turkish public has come to believe that the United States is indifferent toward if not harmful to Turkey’s core security interests.

This sentiment transcends political party lines and has deepened particularly since the American invasion of Iraq in 2003, and more recently because of the United States’ support for Kurdish elements in Syria that Turkey believes are linked to the internationally outlawed Kurdistan Workers’ Party, better known as the PKK.

This background has extensively sensitized the Turkish mindset, diminishing trust in the United States to the extent that according to a 2022 survey conducted by Kadir Has University in Istanbul, 43 percent of the population views the United States as a threat to Turkey.12 This atmosphere has made anti-Americanism increasingly expedient for politicians, representing a reality that opposition parties not only contend with, but at times voluntarily succumb to. For example, when Devlet Bahçeli, leader of the AK Party’s political ally the MHP, floated the idea that Turkey could leave NATO, the chairman of the leading opposition party,13 the CHP, joined the bandwagon by advocating the closure of all U.S. bases in the country,14 though he argued in favor of staying in NATO.

These types of reflexes in relation to the United States can be expected to prevail on the Turkish political scene. They can only be reduced if a positive trajectory is captured in bilateral relations and the public mood shifts, which will undoubtedly require mutual effort. Until such a time, the political opposition will also tread lightly when it comes to advocacy for prioritizing relations with the United States. This will be so despite their expressed interest in developing bilateral relations by overcoming existing challenges, such as the one related to the Turkish purchase of the Russian S-400 air defense system, which the political opposition uniformly agree was a mistake.

On a positive note, opposition party representatives concurred on the importance of Turkey’s bilateral relationship with the United States and the need to revitalize it. They all pointed to the erosion of trust between the two countries as a serious problem and underlined the need to reverse this trend.

There was overall agreement among the opposition that rebuilding trust between Ankara and Washington could facilitate the resolution of at least some existing bilateral problems. Such an atmosphere of enhanced trust would also make it easier to continue honest discussions on outstanding issues. The political opposition considered that this might even increase the chances of solutions on difficult items down the road. Regarding the necessary steps for rebuilding trust, they admitted that Turkey had work to do. But they also made it clear that this had to be a joint effort, with responsibility also resting with the United States. This latter point made it clear that the Turkish public’s disappointment in certain American policies was shared by the opposition parties and that they too, like the current AK Party government, will expect some course corrections to be made in Washington.

The political opposition underlined, for example, their unequivocal objection (except for the HDP) to the U.S. policy of support in Syria for the Democratic Union Party (PYD)—an affiliate of the PKK—and its military wing, the People’s Protection Units (YPG).15 They considered this to be incompatible with Turkey’s national security interests and identified it as a disruptive factor in bilateral relations. The U.S. argument that its engagement with the PYD and YPG,16 including its provision of arms and supplies, was limited to the fight against the self-proclaimed Islamic State was unconvincing to the opposition, just as it has been to the current government. Both CHP representative Çeviköz and İYİ Party representative Erozan conceded that the AK Party’s misguided policies at the time may have paved the way for the American choice to partner with the PYD and YPG in the fight against the Islamic State in the first place. According to Bilgel from DEVA, the AK Party’s policy of active support for dubious armed opposition groups with the intention of regime change in Syria as of 2011 was its most mistaken and costly foreign policy choice. Most importantly, they all stressed that because of its security considerations, Turkey could not tolerate the use of the PYD and YPG as a proxy by the United States. In other words, notwithstanding their criticism for AK Party policies, they echoed the expectations of the Turkish government on this matter, making it unrealistic to expect any change in Ankara’s approach.

The solution to this problem, according to them, could come through a politically negotiated settlement on the future of Syria that would entail full respect for Syria’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. And in the words of Erozan from the İYİ Party, progress on the political track in Syria would eventually make it incumbent upon the regime in Syria, be it under President Bashar al-Assad’s leadership or not, to deal with the PYD and YPG as an internal matter. The view that Turkey would hold the regime in Damascus accountable for any threat coming from Syria was widely shared. Yardım from the Gelecek Party echoed this and added that in the absence of threats to Turkey’s national security, it was up to the regime in Damascus to decide on how it dealt with the PYD and YPG. Özsoy from the HDP differed on that count, arguing that Turkey needed to engage the Kurds in Syria to facilitate lasting stability in the region.

These views (excluding those of the HDP), together with recent debates in Turkey as to whether building ties with the Syrian regime might encourage Damascus to clamp down on the PYD and YPG,17 confirm an overwhelming reality: under no circumstance will Turkey be at ease with a PYD and YPG presence in Syria that it sees as a threat. Therefore, to the extent that the United States insists on supporting the presence and livelihood of the PYD and YPG in northern Syria in a manner that Turkey considers to be incompatible with its security interests, a strong irritant in bilateral relations will remain. This will be the case irrespective of who is in power in Turkey.

There was general recognition among the opposition that Turkey’s aspiration to advance its cooperation with Russia should not come at the expense of its relations with the United States. The opposition criticized the purchase of the S-400 air defense system in this context. All parties spoke of the need to find a way to turn the page on the matter. Erozan expressed his belief that there should be a way to negotiate a solution with the United States and spoke of hints from American officials that this could be possible. The CHP’s Çeviköz, meanwhile, underlined that a solution to the S-400 problem should be followed by Turkey’s reintegration into the F-35 program. Turkey’s exclusion from the program, he remarked, had come at a great cost for the advancement of Turkey’s defense industry.

The political opposition’s comments in relation to the S-400 imply a readiness on their part to actively look for a reasonable solution. But the opposition parties have some expectations of their own, which will require a mutual compromise. In any case, their views represent better prospects for a breakthrough on the S-400 deadlock, and also suggest that the AK Party’s policy of closer defense industry cooperation with Russia will not be continued in a manner that is incompatible with Turkey’s standing as a NATO ally.18 Any such shift and reciprocal positive signaling from the United States could arguably initiate a positive dynamic in Turkish-U.S. relations and be consistent with the expressed intentions of the political opposition in Turkey.

Yardım brought up the plight of the Uyghurs in China as a topic on which Turkey and the United States could find common ground to work.19 He highlighted Turkey’s unique importance for the Uyghurs. He argued that in a normal state of affairs, characterized by trust rather than suspicion between the two nations, Ankara would be a natural interlocutor for Washington. He made the same argument for topics like Iran and the Palestinian issue. This constituted a good example of how, under better circumstances in bilateral relations between Turkey and the United States, Turkey could contemplate a plethora of areas of cooperation.

Regarding the Fethullah Terrorist Organization,20 which Turkey blames for the failed 2016 coup attempt, there were no expectations that the United States would extradite its leader Fethullah Gülen to Turkey. This observation probably conforms to a begrudgingly accepted reality within the AK Party that would explain its comparative silence on the matter lately. Opposition representatives saw greater merit in focusing on encouraging American authorities to clamp down on the activities of the organization in the United States. According to Çeviköz, nurturing a relationship of mutual trust with the United States could also go a long way on this matter.

Turkey and NATO

On Turkey’s place in NATO, there was overall recognition that NATO membership enhanced Turkey’s security by boosting its deterrence and defense capabilities and that it was in Turkey’s interest to safeguard its credentials as a strong NATO ally. This understanding, together with their shared criticism of the S-400 acquisition, suggests that the political opposition parties can be expected to better harmonize Turkish foreign, security, and defense policy choices with the requirements of being a NATO member and reassert Turkey’s NATO identity. More recently, the opposition chose to underline this identity as a reaction to Erdoğan’s statements that Turkey would seek membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO).21 Çeviköz stated,22 for instance, that Turkey should remain an observer in the SCO and membership would be a grave mistake jeopardizing Turkey’s relations with the West.

Erozan lamented that Turkey had gained a reputation as a Trojan horse within NATO by virtue of its disruptive policies and argued that this harmful image had to be corrected. Çeviköz said that under the current government, Turkey had gotten into the habit of transposing its bilateral differences with allies into its policies within NATO. He believed that the idea of bringing bilateral grudges into NATO was a mistake because NATO was a distinct platform representing collective interests and mutual obligations. He noted that the United States treated both Turkey’s S-400 acquisition and its expulsion from the F-35 fighter jet program as bilateral issues, and that the role of NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg had been limited to an offer of support. This, he argued, was an illustration of why these themes required discussions between Turkey and the United States separately rather than within NATO. Turkey, he remarked, needed to make the same distinction about its bilateral disagreements with allies.

Yardım welcomed Turkey’s departure over the years from what he described as a narrow reading of the world through a restricted European and transatlantic prism and commended Ankara’s interest in places like the Middle East and the Balkans. Yet he argued that Turkey’s vocation as a founding member of many European institutions and as a NATO member was clear.

This sentiment on Turkey’s vocation was visible across the board among interviewed opposition representatives. While they concurred that Turkey’s priorities and interests may at times differ from those of its NATO allies and Western partners, they voiced no confusion over Turkey’s Western vocation. This stood in contrast to the increasingly muddled sentiments coming from the AK Party leadership on Turkey’s place in the world and their occasional visceral expressions of distaste for the West.23

Yardım also made the point that many of the challenges identified in NATO documents in relation to countries like Russia and China were relevant first and foremost for Turkey.24 He added that Turkey, like other NATO members, nevertheless had every right to advance its relations with Russia and China. He said that the unwarranted concerns this triggered among Turkey’s allies were more about the erosion of trust in Turkey and its policies, which he believed needed to be remedied.

HDP representative Özsoy argued that NATO was a unique platform but expressed reservations about the intentions and functioning of the alliance. He suggested that NATO was manipulated by a handful of its members and questioned NATO’s sense of purpose as a Euro-Atlantic defense pact that ventured into interventions in faraway places like Afghanistan and Libya. Özsoy was critical of the magnitude of Turkey’s defense expenditures, especially in light of other pressing needs, and advocated a drastic reduction in its defense budget.

Relations with the European Union

On the future of the relations with the EU, there was considerable convergence between the different opposition parties. Firstly, they all agreed that the accession objective should be maintained. Secondly, they shared the realistic assessment that membership, even if achievable, is a long-term objective. Consequently, they all voiced a shared intent to envision and foster deeper cooperation with the EU. Thirdly, there was a shared belief that significant domestic reforms designed to enhance Turkey’s democratic credentials would create more favorable conditions for improving Turkey-EU relations.

The framework presented by the political opposition was reminiscent of the way in which the AK Party approached the EU in the early days of its rule, with then prime minister Erdoğan being the strongest advocate for EU membership, spearheading internal reforms and an extensive effort to align Turkey with the EU. Nowadays, while the AK Party government’s stated objective of joining the EU remains, Turkey is further from that goal than ever before for reasons ranging from political obstacles to Turkey’s membership to internal EU dynamics to backsliding in Turkey in many areas, including on reforms and democratic standards.

The political opposition, like the current Turkish government, is determined to retain Turkey’s goal of full membership to the EU, though İYİ doesn’t rule out other options should they better serve Turkey’s interests. The opposition’s intention to rekindle relations with the EU by returning to a process of internal reform, while retaining a realistic level of ambition on the speed at which the full membership process may progress, could indeed provide a realistic window for a new momentum in the Turkey-EU relationship.

CHP representative Çeviköz articulated this opinion, remarking that relations with the EU were not just a foreign policy issue. He noted that the erosion of democratic standards dealt severe damage to the relationship, raising the government’s refusal even today to comply with the rulings of the European Court of Human Rights on the Osman Kavala case. A former civic leader, Kavala has remained in prison for the past five years on highly debatable charges of conspiracy to overthrow the government, linked to his alleged role in the 2013 Gezi Park protests.25 The CHP view was that it would be indispensable for Turkey to improve its democratic credentials at home to improve its relations with the EU. And as a result, only an ambitious reform agenda would help to transform the Turkey-EU relationship. Çeviköz firmly believed that the EU would be compelled to reciprocate and lift the barriers to deeper integration for Turkey.

İYİ Party representative Erozan remarked that the post-Erdoğan era would present a new challenge for the EU. The slated democratic reforms in Turkey would eliminate the excuse to stall the relationship. He added that shifting sentiment within European public opinion would also create a more favorable environment, given how detrimental the Turkish president’s negative perception in European public opinion has proven to be to the relationship. Erozan claimed that with a new and pro-reform government in Turkey, the terms of the debate in Europe about Turkey would also shift, and instead of emphasizing the cost of Turkish accession, European policymakers and opinion leaders would need to take into consideration the cost of rejecting Turkey.

And yet there is a clear realization that accession is a long-term goal. As Çeviköz has underlined, the mutual erosion of trust, which will take time to repair, and the EU’s evolution have introduced this uncertainty. He remarked that there were competing visions regarding the future of Europe. As a result, he said, Turkey’s policy response should be to seek to contribute to the debate on the future of Europe. This outcome will require Turkish policymakers to follow more closely the developments in Europe that shape its future. It will also necessitate Turkish policymakers to develop cogent proposals to contribute to the EU’s policy agenda. Otherwise, there is a risk that Turkey will become a “policy taker,” a passive party without the ability to shape the future of the political union it aspires to join.

For İYİ, the future of the Turkey-EU relationship will also depend on what sort of global actor the EU wants to become, on how Brussels shapes its relationship with the main non-Western powers like China and Russia, and how the EU aims to relate to the common neighborhood (which covers the Middle East, Africa, and Central Asia). Erozan believes that Turkey would be an asset to an EU willing to constructively engage with these regions, where Turkey has a growing influence. The İYİ Party representative also underlined that ultimately a transformed Turkey should evaluate its position on a global scale and assess whether accession will best serve its national interest. For İYİ, EU membership is not the sole available option for Turkey. İYİ can envisage establishing a mutually beneficial and cooperative relationship with the EU that is not membership-based. For İYİ, therefore, the Turkey-EU relationship is indeed open-ended.

For DEVA, Turkey’s accession process is instrumental as it helps Turkey to upgrade its democratic and economic standards. Ankara can diversify its foreign relations with strong economic and diplomatic ties with Russia and China, but ultimately Turkey should be anchored in the West. Relations with the EU serve this purpose.

The HDP also unambiguously supported the accession objective. HDP representative Özsoy maintained that regardless of whether accession is realized or not, the party views the EU as the only possible strategic ally of Turkey. According to the HDP, Turkey can maintain sound relations with the United States, Russia, and China, but only the EU can be Turkey’s strategic partner. The two have had and will continue to have an intertwined future.

For all the political opposition parties, there is an evident willingness to revitalize the Turkey-EU relationship in the short and medium term by fostering areas of cooperation. İYİ underlined, for instance, the importance of common policies. Erozan remarked that by virtue of the European Union–Turkey Customs Union, there is already a common trade policy and that these ties should be similarly deepened in other economic policy areas. On foreign policy, İYİ is open to exploring the prospect of Turkey’s further foreign policy convergence with the EU. But it is really on refugee policy that İYİ wants a policy reversal. Erozan indicated that İYİ would aim to conclude a new agreement with the EU to create the necessary social and economic conditions within Syria to incentivize the return of the refugees. This outcome is critical for Turkey, he said, adding that Turkey alone cannot achieve this objective and therefore the EU’s contribution remains of crucial importance.

For the CHP, a cooperative relationship with the EU on migration and refugee policy is also very important. Çeviköz pointed out that the EU essentially shaped its approach to migration and refugees and imposed it on Turkey. A more constructive and sustainable alternative would have been for the EU to acknowledge Turkey’s critical role and allow for a joint approach and the formulation and implementation of common policies.

Also a backer of a positive and cooperative agenda with the EU, DEVA proposed to incorporate foreign policy collaboration and cooperation on cyber policies in addition to modernization, the customs union, and an upgraded refugee deal. The HDP underlined the necessity of visa liberalization. The HDP representative stated that the party wants Turkey to complete the remaining technical requirements, including the changes in anti-terror legislation, to obtain visa liberalization. The HDP also supports the modernization of the customs union. It believes domestic reforms would lift the obstacles and pave the way to accession, to the customs union’s modernization, and to visa liberalization.

Eastern Mediterranean, Greece, and Cyprus

The Eastern Mediterranean’s rise as a potential new source of energy has generated competing maritime jurisdiction claims, which have in turn become entangled in the unresolved Cyprus issue and an array of disagreements between Turkey and Greece in the Aegean Sea. This represents three clusters of topics which for geopolitical and historical reasons are highly combustive in Turkey.

There is little daylight among the political elite, governing circles, and the public at large on the significance of these matters for Turkey. This was also evident in the positions taken by the political opposition, who all emphatically underlined the importance of Turkey’s vested interests. Consequently, it is safe to assume that notwithstanding potential nuances in tactics, there would be continuity in Ankara’s general approach on these matters irrespective of who is in power.

The prevailing sentiment among opposition parties is that Turkey has lost considerable ground on the diplomatic front in the Eastern Mediterranean and that, conversely, Greece and Cyprus have played their cards more wisely.

Gelecek’s Yardım said that for Turkey to have a strong negotiating position in the Eastern Mediterranean, it would have to erase doubts over the country’s true place in the world. On that count, he pointed to the need for Turkey to reconfirm its commitment to institutions like the Council of Europe, the European Parliament, and NATO, and to discontinue the habit of engaging in squabbles with its traditional partners and allies in the West. Doing this, he believed, would carry Turkey to a position of strength.

The political opposition believes that the vacuum created by Turkey’s self-inflicted isolation in the region has allowed Greece and Cyprus to foster regional groupings and platforms such as the East Mediterranean Gas Forum at Turkey’s expense.26

The CHP and the İYİ Party argued that Turkey could not realistically expect to reverse current adverse trends or to advance its interests in the Eastern Mediterranean while it has ruptured relations with regional powerhouses like Egypt and Israel. Both parties believe in the need to restore these relations on the basis of sovereign equality and mutual respect. This assertion is arguably corroborated by the AK Party government’s current efforts to reverse Turkey’s regional isolation and to mend fences with countries like Israel,27 Egypt,28 Saudi Arabia,29 and the United Arab Emirates.30

İYİ Party representative Erozan spoke of incalculable losses for Turkey in the Eastern Mediterranean, particularly in relation to emerging dynamics around gas exploration rights and energy interests. He said that the apportionment in these areas had already been concluded in Turkey’s absence. Pointing to the deepening partnership between Greece and Egypt, he also argued that Turkey’s hopes of instilling doubts in the minds of the Egyptian leadership about the expediency of their maritime delimitation agreement with Greece were futile under the current circumstances. According to Erozan, Turkey’s leverage over Egypt would only grow to the extent that the latter is convinced of Turkey’s continuing influence in the region, as well as of its indispensable role as a political and economic actor. Rebuilding this perception in Egypt, he believed, would make it difficult for Cairo to overlook Ankara’s interests. He voiced skepticism over Libya’s long-term commitment to the maritime boundary agreement that its internationally recognized government had signed with Turkey,31 particularly in view of the mixed messages coming out of Libya as to whether or not the agreement needed parliamentary ratification to be valid.

On Israel, the CHP’s Çeviköz argued that the Palestinian issue would form an inseparable part of Turkey’s agenda. He underlined the importance of goodwill on all sides in these engagements and said that on its part, Turkey would have to refrain from antagonizing its counterparts on issues like the Muslim Brotherhood or Hamas. He contended that the current government’s ideological and sectarian outlook on the region would have to be abandoned.

When it comes to bilateral disputes with Greece, opposition parties again point to Turkey’s isolation as a disadvantage. They argue that the AK Party’s misguided policies have led to increased international sympathy for the positions held by Greece.

In contrast to the multiplicity of actors and interests involved in the Eastern Mediterranean, the İYİ Party’s Erozan argued that the bilateral nature of Turkey’s disagreements with Greece makes them less complex. He stated that Turkey’s approach to these long-standing problems had evolved into a form of state policy that stands above politics. He was hinting at continuity. He also suggested that different areas of disagreement with Greece, such as those pertaining to sovereignty issues in the Aegean or the status of the Turkish minority living in western Thrace, would need to be taken up in separate baskets, given their distinct nature.

CHP representative Çeviköz spoke of the need for Turkey and Greece to drop the mental baggage they both carry in relation to one another. The Greek perception that Turkey is a threat and the Turkish idea that Greece is an enemy need to be overcome. As the best way forward, he advocated frank and transparent talks but stated that these meetings needed to be well structured, include time frames, and have some built-in method of measuring success. He saw no value in talking for the sake of talking. The CHP realistically assumes that it may not be possible to reach a negotiated settlement on all issues and concludes that both sides should be ready to take outstanding matters to the International Court of Justice.

The CHP representative also highlighted the need to complement efforts to resolve disagreements with more significant interaction among the two countries’ peoples, including through business and cultural contacts. He brought up the idea of jointly implementing mutually beneficial projects and gave the example of the Greek island of Kastellorizo, which must go to great lengths to transport its water from other parts of the country. Given the island’s immediate proximity to mainland Turkey, a joint project to provide water from Turkey could be considered. Likewise, he pointed to the contributions made by Turkish tourists to the livelihood of Greek islands in the eastern Aegean and concluded that the two countries could jointly work on economic strategies that would benefit both sides and help alleviate each’s negative perceptions of the other.

The overall implication of these observations is that if Turkey were to experience political change, the AK Party’s belated attempt to reengage with the region would be continued with even greater vigor and Ankara would prioritize its diplomatic outreach efforts. This is not to say that Turkey would rule out muscle flexing under extreme circumstances, but this would most probably be the exception, both in rhetoric and in practice.

The HDP has a unique take on Turkey’s current approach to matters in the Eastern Mediterranean and its relations with Greece. Its representative, Özsoy, suggested that Turkey’s current policy on these issues is framed in a manner that aims, above everything else, to energize a sense of Turkish identity. Every contentious matter, he argued, is deliberately interwoven into the narrative of national identity. Building such a linkage, he said, makes it practically impossible for Turkish officials even to consider negotiated settlements, since every concession on their part would be perceived as coming at the expense of the Turkish identity.

There is convergence among opposition parties on the need for the Turkish government to recognize the right of the Turkish Cypriots to take decisions independently in negotiations with their Greek Cypriot counterparts, albeit in close coordination with Turkey and with consideration of Ankara’s interests.

The CHP and İYİ were critical of the current Turkish government’s meddling in Turkish Cypriot domestic politics and argued that this, as well as its attempts to prescribe negotiating positions for the Turkish Cypriots, contravened Turkey’s assertion that Turkish Cyprus was an independent and sovereign state. All opposition representatives made similar points, reflecting their desire to recalibrate Ankara’s attitude toward the Turkish Cypriots.

Affording the Turkish Cypriots greater room for decisionmaking in this manner would also have implications for the two-state solution lately advocated by Ankara.32 Erozan expressed skepticism about how Turkey had raised the idea. He pointed out that in contrast to the generally recognized parameters for a solution under the UN framework, which envisage a bi-zonal, bi-communal federation between two equal constituents, no other country but Turkey seemed to embrace this new route. He added that the parameters of a solution would have to be found and agreed upon by the Turkish and Greek Cypriots and that at that point, Turkey’s security interests would have to be recognized as well.

The CHP’s Çeviköz, who also did not rule out the possibility of a two-state solution, expressed similar concerns over how Turkey had floated the idea. Both the İYİ Party and CHP representatives pointed to the fact that many Turkish Cypriot politicians still believed in the merit of continuing negotiations under established parameters within the UN framework. Therefore, they argued, it was only after that option was fully exhausted, and particularly Turkish Cypriots overwhelmingly thought so, that the two-state solution should be raised. Çeviköz said this sequencing was necessary to make a convincing argument on the need for a two-state solution. Yardım from the Gelecek Party agreed, adding that the essential elements for a two-state solution were already in place on the island but tactically speaking, it was simply not the right time to advance the idea. This implies that while they do not challenge the merits of a two-state solution, the opposition would be ready to continue negotiating along the old parameters, particularly if the Turkish Cypriots preferred to do so.

Çeviköz spoke about the potential for the United Kingdom to make a fresh contribution to the negotiations as one of the three guarantor powers on the island,33 together with Turkey and Greece. He premised this idea on the belief that since leaving the EU, the United Kingdom may feel less restrained, having broken the shackles of EU solidarity, and be able to take a more objective stance on the matter. He recognized the United Kingdom’s particular interests on the island and conceded that many people in Turkey carried doubts over London’s intentions, but still considered this potential to be something to think about.

Syria

During its more than twenty years of rule in Turkey, the AK Party government’s approach to Syria has been by far its most consequential foreign policy decision. It was the wave of the Arab Spring that eventually engulfed Syria and changed its destiny with implications beyond. But it was Turkey’s departure from the traditional parameters of its foreign policy, by getting directly involved in the internal matters of a neighboring state, and Ankara’s declared goal of regime change in Damascus, that marked the beginning of a new and difficult chapter for Turkey.

Today, the burden of hosting more than 3.5 million Syrians is becoming increasingly costly for Turkey,34 making it a leading topic of debate on the domestic political scene. Resentment toward Syrians and other migrants is on the rise, coming with greater criticism in the public domain for Turkey’s Syria policy under AK Party rule. Meanwhile, Turkish officials, including Erdoğan and Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu,35 are giving early signs of an attempt to reverse policy and engage the Syrian regime with a view to addressing Turkey’s security concerns and facilitating the return of Syrians to their homeland.

This is all taking place against the backdrop of a global phenomenon of economic hardship that has weighed on Turkey, even more so because of economic mismanagement causing runaway inflation and a dramatic depreciation of the national currency.36 This has brought Turkey’s Syria policy into the limelight as never before and the stakes could not be higher for the AK Party government, with presidential and parliamentary elections looming on the horizon.

The political opposition is uniformly firm in its belief that it was a mistake for Turkey to venture into the domestic affairs of Syria. Championing regime change and using proxies to this end were miscalculations that ultimately undermined Turkey’s interests.

The opposition’s thinking on Syria policy can be examined under three main headings: dialogue with the Syrian regime, uncontrolled migration and the future of Syrians currently in Turkey, and PYD/YPG presence in Syria and Turkey’s related threat perceptions.

Dialogue With the Syrian Regime

On whether Turkey should contemplate initiating a dialogue with Syria, the opposition recognizes that with external support, the regime has been able to fend off challenges to its existence and is slowly making progress in breaking out of its isolation. The opposition takes a realistic approach and understands that as tainted as it may be, the regime in Damascus needs to be the interlocutor on Syria.

CHP representative Çeviköz argued that Ankara should never have broken off political dialogue with Damascus. The current practice of meetings among intelligence agencies was useful but insufficient, since their remit is limited. They cannot substitute for the necessary holistic engagement, including on political and economic matters, as well as on large issues like uncontrolled migration. The CHP’s choice to send representatives to meet with the Assad regime on two occasions in the past was a function of this understanding. Çeviköz addressed the conundrum of dealing with such a tainted regime by compartmentalizing practical engagement with Assad’s regime and the judicial process on Assad’s atrocities that would most probably involve the International Criminal Court. According to Çeviköz, these two were separate tracks.

The İYİ Party holds similar views on the merits of a functioning dialogue with Syria. The nature of the regime in Damascus was a secondary consideration in the face of this practical need. Erozan highlighted Ankara’s changing attitude toward Assad, which had mutated from exaggerated expressions of fraternity to an outright effort to overthrow him, attributing this policy reversal to religious and sectarian considerations that incrementally blinded the Turkish government’s eyes. Qatar, according to him, was instrumental in nurturing the mindset in Ankara that made toppling Assad a priority—the first policy of its kind in the history of the Turkish Republic.

DEVA’s Bilgel also saw virtue in having a political dialogue with the Syrian regime, particularly to manage existing challenges affecting Turkey. Yardım from Gelecek conceded that Turkey needed to act according to evolving realities on the ground and engage with the regime in Damascus, but categorically ruled out the proposition of making peace with Assad, a leader he described as having blood on his hands.

Uncontrolled Migration and the Future of the Syrians Currently in Turkey

Managing the flow of unchecked migration from Syria and offsetting related challenges is an area of leading concern among opposition parties. The rising visibility of this topic among the Turkish population and growing frustrations do not escape their attention.

İYİ’s Erozan said that the European Union had turned Turkey into a bulwark against migrants from Syria. He argued that European funds were allocated to projects focusing on integrating Syrians in Turkey, whereas the primary aim should be to facilitate their sustainable return to Syria. Turkey, he stated, could match every penny allocated by the European Union, on condition that the money was spent on establishing the right environment for the Syrians to return to their homeland. He cited Turkish government figures that over $50 billion had been spent on assisting Syrians and remarked that Turkey might need to spend another $50 billion in the coming decade to encourage their return to Syria.

Çeviköz laid out some elements of a possible way forward. As a first step, the necessary physical conditions for basic livelihood, including living spaces and employment opportunities, must be restored in Syria. Along with these steps, critical services such as education, health, and security need to be brought up to speed. Turkey cannot be expected to shoulder the financial burden for all this work on its own. Therefore, Çeviköz said, international financing through a solidarity fund and the support of the UN and the EU would be necessary. Meanwhile, Turkey could undertake the realization of some projects while Turkish businessmen and conglomerates, particularly those active in the eastern parts of Turkey, could be incentivized to invest in Syria. These efforts would create new jobs and opportunities for Syrians in their own country, encouraging the voluntary return of Syrians to their homeland. Çeviköz stressed the need for returns to be voluntary.

Yardım agreed on the need to focus on the voluntary return of Syrians to their country of origin and discredited statements advocating their forced repatriation as being nothing more than populistic rhetoric. So long as the Syrians are willing, Turkey should actively facilitate their return to Syria. Yet Yardım was realistic in his assessment that some Syrians would be likely to stay in Turkey.

Both the İYİ Party’s Erozan and the CHP’s Çeviköz also recognized that some Syrians had successfully established themselves in Turkey by building a legitimate livelihood with their families, which makes it unrealistic to expect them to leave. But such examples constituted the exception, meaning that well-articulated policies geared toward voluntarily repatriating most of the Syrians were necessary.

Çeviköz pointed out that Syrians contemplating returning to their country would look for credible assurances that they would not be persecuted. Then, as a personal thought, Çeviköz suggested that Assad might choose to refrain from targeting returning Syrians simply to rebuild a semblance of legitimacy for himself.

The HDP’s Özsoy recalled times when the Turkish government enthusiastically encouraged Syrians to come to Turkey and argued that the arrival of over 4 million migrants from Syria was a direct function of Turkey’s misguided attempt to prescribe military solutions to existing challenges.

DEVA’s Bilgel took a broader look at the problem of uncontrolled migration and opined that Turkey’s challenges would grow in the coming years because of its central location on migratory paths. She concluded that while the current focus is on Syrians, the looming prospect of millions of additional migrants from different countries obliges Turkey to take a leading role in global efforts to manage this growing challenge. She added that with the end of the war in Syria, DEVA will prioritize policies that would, in cooperation with the international community, accelerate the safe return of Syrians currently in Turkey to their homeland.

The Turkish electorate expects to see the process of having Syrians reintegrated into their own homeland set in motion. A fringe political actor on the far right, Victory Party leader Ümit Özdağ,37 has been able to rally voters around this call, unleashing a growing sentiment in the public domain that had hitherto remained mostly under the surface. This promises to be a topic where convincing arguments and policy formulations will go a long way in appealing to the electorate.

PYD and YPG Presence in Syria and Turkey’s Threat Perceptions

Apart from the HDP, opposition parties view the presence and activities of the PYD and YPG in Syria as a serious source of concern, primarily undermining Turkey’s national security interests. How to deal with the PYD is a more contentious topic: the CHP sees merit in the idea of engaging them as Turkey has previously done, but the İYİ and Gelecek Parties object. The HDP, unsurprisingly, is the strongest advocate of talking to the PYD. There is general agreement that the decision on the Syrian state’s future structure belongs to the Syrians. The bottom line emphasized in this context by the CHP, İYİ, DEVA, and Gelecek is that Syria cannot be allowed to become a haven for terrorists.

The CHP’s Çeviköz said that the current Turkish government had previously held talks with the PYD, and that this could be considered again. He believed that contacts could be utilized to impress upon the PYD the limits of what is realistically achievable for them in Syria. While doing so, it would also be possible to remind the PYD of the example of Iraq, where the Kurdistan Regional Government’s quest for independence in 2017 was stopped in its tracks at the behest not only of Turkey but also of other nations.38 He remarked that Syria, Iraq, and Iran, like Turkey, each have varying degrees of concern about such aspirations by Kurds in the region. This was a reality that the PYD needed to understand. Engaging the PYD might help push this message through. Dialogue with the PYD might also help prevent the ossification of current problems, which might otherwise become inevitable.

İYİ’s Erozan differed on the idea of engaging with the PYD. He said it had been a mistake to do so in the past and should not be repeated. Yardım from the Gelecek Party also saw no basis for talks with the PYD. In contrast, the HDP’s Özsoy strongly argued in favor of the idea and believed there was no other reasonable way to address Turkey’s perceived security concerns in Syria.

The divergence of views among the opposition on whether to engage the PYD mostly evaporated when considering the responsibility of the Syrian regime in preventing threats directed at Turkey. Both Erozan and Yardım said that the Assad regime would be responsible for any form of threat emanating from Syria and be duly held accountable. Erozan objected to notions like safe zones or secure pockets and stated that Syria as a whole needed to be free of threats targeting Turkey. The CHP’s Çeviköz and DEVA’s Bilgel agreed. Bilgel added that Turkey should as a matter of principle always choose to engage with central governments as opposed to nonstate armed groups. Governments, she argued, could always be held accountable, whereas in the case of nonstate actors that might not be possible.

Erozan expected aspects of the Syrian state, like its structure and constitution, to be determined through talks in Geneva.39 He assumed that the destiny of Syrian territories east of the Euphrates that are currently controlled by the PYD and YPG would also be part of those negotiations. Turkey had to do whatever was necessary to stand up against endeavors by the PYD and YPG to establish cantons on Syrian territory and to preserve its territorial integrity. Turkey, he argued, could forestall developments it deems detrimental to its interests by working with the Syrian regime, which he described as Turkey’s natural partner in containing the aspirations of the PYD and YPG. He recalled that while the Americans and Russians had chosen to refrain from referring to the PYD and YPG as terrorists, Assad had been doing the opposite until Turkey turned its back on him, obliging Assad to seek a modus vivendi with the PYD and YPG.

Both Çeviköz and Erozan believed that the eventual resolution reached for the Kurds in Syria would probably not be Turkey’s preferred option and would resemble the one found for the Kurds in Iraq—some form of autonomy. Çeviköz remarked that provided this happens through the legitimate blessing of the Syrian people, Turkey would need to come to terms with it. He added that in such an eventuality, Turkey’s dialogue with Damascus would become even more critical to keep greater ambitions among Syria’s Kurds in check.

The Gelecek Party’s Yardım agreed with this forecast. He remarked that the Kurdistan Regional Government in Iraq had come into existence as an entity primarily because of Turkey’s mistaken policies in the past. He stated that the future of the Kurds in Syria, including their prospects of attaining some form of autonomy, would in the end be Syria’s problem to deal with. However, he was unequivocal about not advocating such an outcome. Yardım added that under no circumstance could Turkey allow any such potential development to constitute a threat to its national security.

DEVA’s Bilgel made the same comment and added that as long as Syria did not become a source of threat, Turkey could live with any peaceful solution that respected democratic principles and allowed for the fair representation of all ethnic groups in the country. She added that, in addition to immersing itself in the country’s domestic dynamics, Turkey’s mistake in Syria had been to take an exclusively military focus when prescribing solutions. Turkey needed to make better use of diplomacy and utilize the benefits of its military prowess together with other elements of its national power.

The HDP’s Özsoy said that the struggle for influence in Syria had been long-standing and that the stability and well-being of Syria and the Middle East were always intertwined. He believed Iraq and Libya had been fragmented almost beyond repair, and Syria had suffered a similar, if not worse fate. This made it hard to contemplate easy solutions. The feasible way forward was to allow the Syrians to settle their differences among themselves without meddling in their affairs. He remarked that Turkey, Iraq, and Syria all had a Kurdish population and that for Turkey to be able to solve its problems with the Kurds in Syria, it had to settle its differences with the Kurds in Turkey first. The road map for this, Özsoy said, involved talking to the PKK. He did not believe Turkey could chart itself a steady course in the Middle East without doing this.

A related topic in the context of Syria is Turkey’s ongoing military presence in the country. The HDP stands out as the only party unequivocally against this. Other opposition parties believe that Turkey currently cannot afford to withdraw its military forces from Syria. Both the CHP’s Çeviköz and the Gelecek Party’s Yardım stressed that Turkey could only contemplate withdrawing from Syria when the circumstances were normalized and Turkey’s threat perceptions were addressed. Çeviköz added that when the time comes, a withdrawal plan with timelines could be prepared.

As for Turkey’s use of proxies in Syria, the political opposition expressed concerns with the practice. Erozan remarked that while Turkey had assembled the Free Syrian Army, it now faced the challenge of religious fanaticism prevalent among its fighters. Bilgel also saw risks in these engagements and agreed that Turkey was confronted with the associated challenges of disengaging with such actors in Syria. She was worried about them becoming a security threat to Turkey. Çeviköz made the point that these fighters were predominantly Syrian. Therefore, they had to be factored in when devising solutions to the country’s problems. Policies of disarmament and their reintegration into Syrian society could be formulated. This, he believed, could also be an item for discussion between Ankara and Damascus. In any case, all three representatives agreed Turkey needed to permanently close this chapter of using proxies, signaling that their parties would put an end to the practice in the event of political change following the elections.

Relations with Russia and China

The political opposition advocates a positive agenda in bilateral relations with Russia and China. The parties see no contradiction between this aspiration and Turkey’s Western vocation or its commitments as a NATO member. The opposition is also generally supportive of the government’s calibrated approach to Russia in the post–Ukraine war era. But the parties have criticized the deepening of economic cooperation with Russia, flagging that these moves could expose Turkey to secondary sanctions.

This reflects a widely shared understanding in Turkey of the shifting global order and the related conclusion that Turkey should no longer see the world through a binary prism of East versus West, but rather according to the realities of a multipolar world order. Russia and China are considered major actors one must get along with, if not by choice, then out of obligation. Russia, despite its economic and democratic shortcomings and even in the aftermath of its attack against Ukraine, is seen as a powerful neighbor that geography dictates Turkey contend with. China, on the other hand, is accepted as a rising consequential actor with whom Turkey is better off building a cooperative relationship.

This is the general framework in which the political opposition sees Turkey’s relations with Russia and China. These groups’ aspiration toward a nonconfrontational relationship with both countries corresponds to the current AK Party government’s approach. But they criticize how the government has handled these relations and advocate different tactics that are more consistent with their understanding of Turkey’s place in the world and would, in their view, better serve its interests.

The main problem the political opposition identifies with the AK Party’s strategy is the self-inflicted state of confusion around Turkey’s intentions regarding its relations with Russia and, to a lesser extent, with China. Turkey, they believe, is giving the wrong signals to both countries and is creating a global perception that puts into question the country’s political trajectory. This creates the dual effect of unwarranted expectations or avoidable tensions with both countries and frustrations among Turkey’s Western partners and allies. The political opposition parties attribute this to Ankara’s incoherent messaging and actions, which they consider to be in turn a result of Turkey’s underperforming executive presidential system.

They prescribe two solutions: firstly, a return to institutionalized practices in the conduct of foreign policy and secondly, a clearer and more explicit presentation of Turkey’s interests and concerns, coupled with consistent action.

On Russia, the personalized nature of the relationship today, steered exclusively by the two countries’ presidents, is something that the opposition representatives believe is harmful to Turkey’s interests and needs to change. The opposition calls for reinstituting the practice of traditional diplomacy through established channels, which would, in turn, allow for more transparency. According to the CHP’s Çeviköz, this would also introduce structure and balance to the relationship.

Çeviköz expanded on this, contrasting the current situation with Turkey’s ability to successfully manage its relationship with the Soviet Union even during the height of the Cold War. He saw no reason this balance should not be possible with Russia today. A fresh challenge, according to him, lies in the current asymmetry of the relationship, given Turkey’s comparatively higher degree of reliance on Russia in various areas, most notably for its energy needs and tourism income.

Turkey’s increasing vulnerabilities toward Russia are a common concern among the opposition parties. They insist that imbalances in the relationship handicap Turkey and need to be redressed.

İYİ Party representative Erozan suggested that Turkey’s foreign policy blunders had given Russia the upper hand in many instances. He pointed to Syria, where Russia had profited from Turkey’s mistakes and consolidated its presence. He said that Turkey needed to calculate the implications of its actions better beforehand, suggesting, for example, that the liberal fashion in which the government was marketing drones in conflict zones, including to Ukraine or other countries like Ethiopia and Morocco, was a mistake. He thought this could result in backlashes down the road from disgruntled countries that have borne the brunt of these weapons. This could, in turn, undermine Turkey’s interests. On a related but separate note, he called for enhanced parliamentary oversight in arms sales and for the development of a national arms export policy.

The Gelecek Party’s Yardım bluntly stated the need for a total overhaul of the relationship with Russia, suggesting that Turkey lacked any coherent policy or consistent messaging. He believed that Turkey’s actions were primarily a function of domestic political considerations, often leading to populistic rhetoric. He conceded the need for Turkey to manage its relations with all prominent actors, given the complex geostrategic environment in which it finds itself. Yet he believed Turkey should be consistent with its chosen vocation of integration with Western institutions. Embracing such a principled stance, he thought, was the only way for Turkey to earn Russia’s respect and meaningfully protect its own interests.

The CHP’s Çeviköz made a similar point on the need for clarity and honesty when dealing with Russia. Turkey, he said, needed to make it abundantly clear that no aspect of its NATO membership was up for discussion. However, he also said that Turkey was ready to advance its cooperation with Russia in other areas that did not conflict with alliance commitments. Accordingly, purchasing arms or military collaboration could not be part of that agenda. A clearly defined framework of this nature would constitute a viable basis for managing and developing relations with Russia. The two countries could also hold frank discussions about Black Sea security in a manner that might help assuage Russia’s concerns about Western and particularly American presence in the region.

Özsoy from the HDP expressed the need for Turkey to recalibrate its relations with Russia. He also argued for consistency with Turkey’s other international commitments and directed criticism at the government’s tendency to opportunistically try to play Turkey’s Western allies and Russia against one another.

Adding a historical perspective, Erozan from the İYİ Party pointed out that Turkish-Russian diplomatic relations had first been initiated as far back as 1492. Of these five hundred–plus years of interaction, 90 percent have been characterized by peaceful coexistence, with the state of conflict being an exception. Turkey and Russia should be able to emulate this overwhelmingly positive experience today. Erozan added that there were some natural limits to bear in mind. Turkey, for example, needed to abandon unrealistic assumptions about how far it could take its relations with Russia. He said the current government had created wrong impressions about this, misleading the Russians and frustrating Turkey’s Western allies.

As far as China is concerned, the political opposition argued in similar fashion that Turkey had to thread the needle between its interests in sustaining a positive relationship with such a significant global power and its responsibilities as a Western NATO ally. They had three primary considerations: Firstly, Turkey should not be dragged into a confrontational encounter with China at the behest of other actors, most notably the United States. Secondly, the rise of China is inherently accompanied by opportunities as well as challenges. Thirdly, Turkey cannot remain indifferent to the situation of the Uyghurs, but this requires careful handling.

The CHP’s Çeviköz stated that Turkey did not have to take sides in the rivalry between the United States and China. The EU was trying to stay out of that binary dynamic, and so should Turkey. He recognized that China was an economic competitor not only for the United States and the EU but also for Turkey, especially in Africa. Yet this should not generate anti-Chinese policies or sentiments in Turkey. Çeviköz supported Turkey’s one-China policy, which he stated should not preclude Turkey from seeking opportunities for cooperation with Taiwan.