Emmanuel Castillo (Follow)

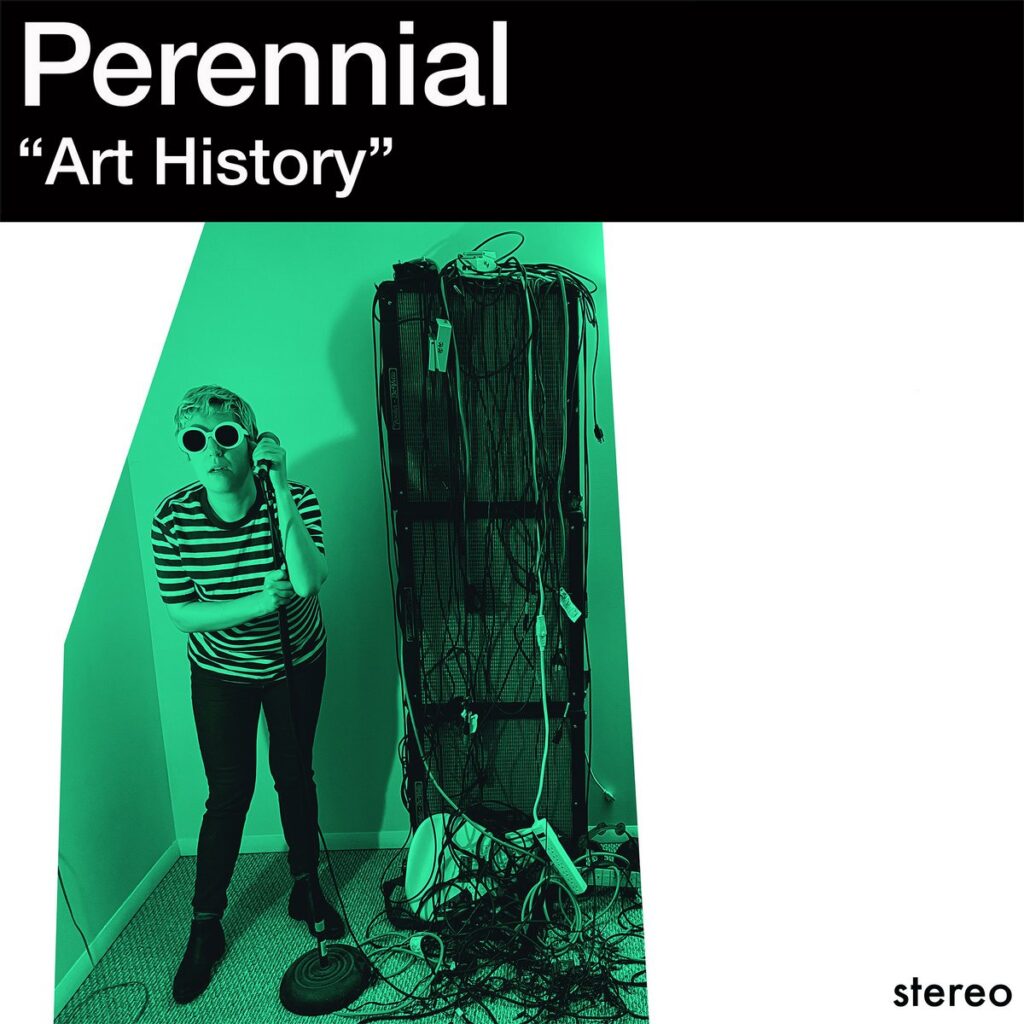

Connecticut art-punk band Perennial returns with dance-friendly songs, a stronger connection to the studio as an instrument, and new finesse. Their operating principle is something like “simplicity is a virtue,” and they’ve been honing their raison d’être over the course of their LP: for the sake of art itself, your richness, and your connection to the world around you. Attempting to bridge the gap between dance and headphone records, Perennial crafts Art History, their most dynamic album to date, without straying from the concise, punchy songs they’ve honed their craft on. Since they make the visual aesthetic a key part of their message, it made sense to extend that appeal to the songs, infusing the album’s sonics with elements taken from the visual arts, giving the songs a new engine aside from their anthemic effects (and they are great anthems).

The hallmarks of their sound are here: vocals that never lose their high energy, electric organ rumbles, incredibly thick guitars, and drum patterns that eschew rock excess for all it’s worth, as if Ringo Starr had replaced Keith Moon in The Who. There’s a greater emphasis on texture than on the previous album, which is evident in both the playing and the supporting instruments. Chad Jewett has proven himself adept at throat-shredding shouts, but this time he challenges himself, stretching his range and stripping it down to the softest touch possible. His and Chelsea Hearn’s exchanges have also improved, with the two taking turns on sections and subverting expectations to keep things interesting. The one-two punch of “Up-tight” and “How the Ivy Crawls” is perhaps the best evidence of this, with Hearn starting each track with his own vocals before handing the baton to Jewett for the quieter sections. Where there were no vocals on the previous album, here he features a warmer voice.

This time, the band is closer to Q and Not U than Fugazi. Confident in the strength of their ideas and eager to please the audience, it gives the impression of a sincere attempt to turn pleasing the audience into a creative challenge, not a compromise. In fact, they take this as an opportunity to further fine-tune their 60s and garage rock influences. The result is an emphasis on showmanship, longer pauses in the melody but still maintaining a choppy attack, and tempos slowing and speeding up for small sections at a time. And that change appears early on in the title track, featuring electric organ drones and accented guitar stabs over a never-ending propulsive drum pattern. The song is successful in emphasizing space, with the guitar disappearing for a few bars, returning again later in the bars, and disappearing again with a languid, whimsical feel. The electric organ gives a unique sense of ease, with sustained notes that sound pleasing to the ear, while the riff returns and cuts through everything.

Soundscapes are scattered throughout the album, but two songs in particular get their own tracks: side one, “A is for Abstract,” spins on a single-line synth melody that seems to hold random notes but is reminiscent of a ticking clock. It sounds as if the band is in a lab, searching for an evolving rhythm or a reason to mix different sounds, like a tambourine hitting a minimal drum machine. “B is for Brutalism” takes this idea even further, with the drum machine pounding away, albeit relatively soft compared to what Wil Mulhern can do behind the drums. Both songs give the impression of a peek into a work in progress, yet both feel like fully formed iterations of the ideas they’re exploring. The best version of this flirtation with abstract expressionism is “Action Painting.” The track transforms the titular painting technique of instinctively waving brushes and splashing paint on canvas into a visualization of a frenetic dance number that’s as visceral, mystical, and revelatory as the title suggests. It’s easy to imagine yourself in the role; the song’s riff thumps along at each bar boundary, and when it fades away, it feels like a breath of fresh air before heading back out onto the dance floor.

Soul elements are present throughout the lyrical content, and the way they use repetition to evoke emotion is more assured than ever, but when they appear in the instrumentation, they are highly effective. “The Mystery Tone” emphasizes this with fuzz bass and an outro that sounds like a storm of horns without actually using any horns. Their interest in soul blends well with their tendency to anthropomorphize the abstract, rendering musical components both surreal and romantic (the juxtaposition of “The metronome thumps!” and “My heart beats like a tambourine!” on “Art History” is understated and moving in its musical bluntness). When they revisit this idea on “Tiger Technique,” perhaps alluding to the shape of Jewett’s hands when performing the bends that are the song’s most distinctive element, they take it to another level, building tension with each repetition.

Part of what’s fun about Perennial is how daring they are within the constraints they set for themselves as a band. They’re simultaneously maximalist and minimalist, following in the same vein as Bowie and Talking Heads: a band confident in their abilities as lyricists and performers, and trying to make their records as widescreen as possible. The band’s approach is unconventional for our time: it’s erudite art that says a lot about its worldview, eschewing the personal lens in favor of a collective one, leaving impressions rather than emotional snapshots. It’s not mystical or pretentious. They’re just confident they’ve made something worth spending time on, and they continue to prove themselves right. It’s the ideal path for a young band more interested in crafting their own shared language than being a soundtrack playing in the background of your life. Art History pushes their breathtaking creativity even further, making it Perennial’s most enjoyable record, the closest they’ve come to capturing the joys of immediacy, composition, and problem-solving all at once.