Steve Preston

Special article from NKyTribune

We are pleased to bring you an encore presentation of an article that first appeared in Our Rich History on July 1, 2019.

On July 3, 1792, 10-year-old Oliver Spencer, his two sisters, and several other guests left the Columbia settlement and boarded a military ship bound for Fort Washington. They were on their way to celebrate Independence Day, the Fourth of July, which was expected to be a grand event and a respite from life on the frontier. Military drills, parades, dinners, and a ball hosted by the fort’s officers were just some of the planned celebrations.

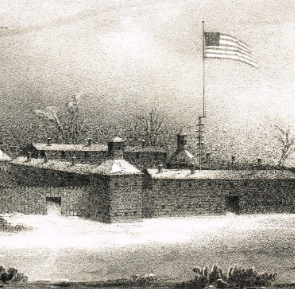

After an hour’s voyage, the group arrived at a dock beneath the whitewashed wooden walls of Fort Washington. Young Spencer must have had a hard time sleeping that night, anticipating the events of the next day.

Fort Washington, Cincinnati. (Source: Charles Sisto, Sketches and Statistics of Cincinnati for the Year 1851, Cincinnati: Wm. H. Moore & Co., 1852, opposite p. 44.)

Fort Washington, Cincinnati. (Source: Charles Sisto, Sketches and Statistics of Cincinnati for the Year 1851, Cincinnati: Wm. H. Moore & Co., 1852, opposite p. 44.)

There was great pride and effort put into the celebrations, as many of the people in the fort and in the local community were Revolutionary War veterans, including military men such as Northwest Territory Secretary Winthrop Sargent, Lt. Col. James Wilkinson, and David Ziegler, Cincinnatians such as the Reverend James Kemper, John Riddle, Benjamin Stites, and Colonel Oliver Spencer, and the town’s largest landowner, John Cleeves Sims, who had all been involved in the war.

According to Oliver Spencer, the morning of the 4th began with a 13-gun salute from the fort’s cannons, which was repeated at noon. The garrison of Fort Washington paraded around in military uniform, performing military drills, to entertain the citizens. This was also likely an attempt to boost morale of both soldiers and citizens after St. Clair’s defeat the previous November. The American forces under St. Clair were routed by a force of 1,000 warriors from the Pan-Indian Confederacy, suffering over 80% casualties. Indian depredations continued unchecked, making daily life miserable for many settlers.

The dinner hosted by the fort was a magnificent affair, with plenty of wild game from the surrounding forests, including turkey, deer, and bear. Military staples like beef, bread, and of course, rum were also served. Large tables were set up on the parade grounds, where guests and soldiers enjoyed the food prepared for the day. Numerous toasts were made to the veterans in attendance, the fallen soldiers, and, of course, George Washington. Everyone ate until they were satisfied or were distracted by other celebrations.

As the night drew on, Spencer described a “great fireworks display.” Many of the displays we enjoy today took place within the stockade of Fort Washington: rockets exploding in the air, sparking cone fountains, spinning sparking wheels, and of course, firecrackers. One can only imagine what the Native Americans thought when they saw them.

Later in the evening, the mood became more formal, and the garrison officers held a ball. Junior and senior officers, especially the younger officers looking for company on the lonely frontier, wore their best uniforms. The garrison commander, Lieutenant Colonel James Wilkinson, was known to wear some rather flashy uniforms for such occasions. Always an entertainer and socialite, he blended in with the crowd. Music was provided by the military band. Upbeat tunes were played, and the guests danced minuets, allemandes, jigs and reels. Dancing continued late into the night, and everyone would have enjoyed the merrymaking.

For those who had enjoyed the night too much, it was probably a slow morning, as the fort and its garrison awoke to business as usual: defending the settlement from marauding Indians, monitoring boat traffic on the Ohio River, and carrying out the daily military duties of any frontier soldier.

The men and women of Cincinnati would have gone back to work, as they do today, eking out a living and raising their families in the wilds of southwest Ohio. Children like Oliver Spencer would have found more fun, staying two more days before they were ready to leave for Columbia. But that’s a story for the future.

Steve Preston is the director of Heritage Village Museum. He received his MA in Public History from Northern Kentucky University.

Dr. Paul A. Tenkotte is a professor of history and gender studies at Northern Kentucky University (NKU) and editor of the weekly series “Our Rich History.” He can be reached at tenkottep@nku.edu. Dr. Tenkotte is also co-director of the ORVILLE Project (Ohio River Valley Innovation Library and Learning Enhancement Project). For more information, visit https://orvillelearning.org/.