Executive Director Dwayne Hopkins (center) talks with Doug Norton and Cindy Leonard as they bag whole chickens for customers to pick up the next day at the South Portland Food Cupboard on May 22. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Every week, Dwayne Hopkins feels like he’s rolling the dice and hoping there’s enough food in his South Portland food pantry.

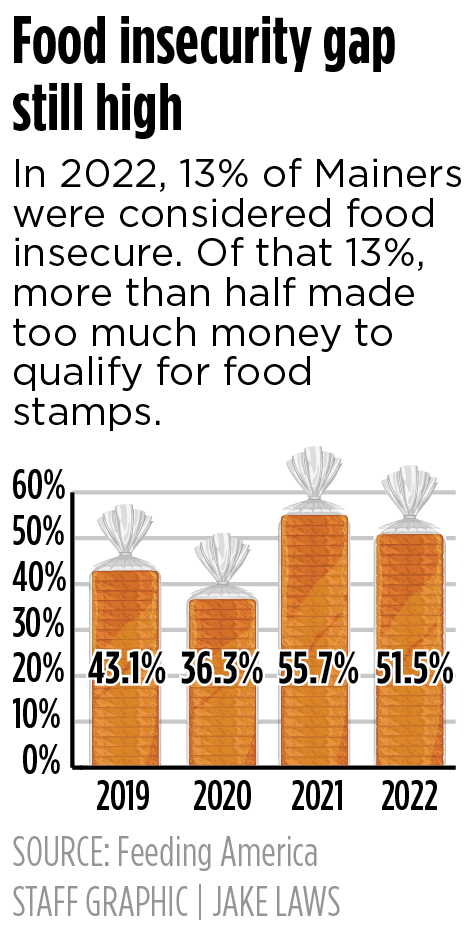

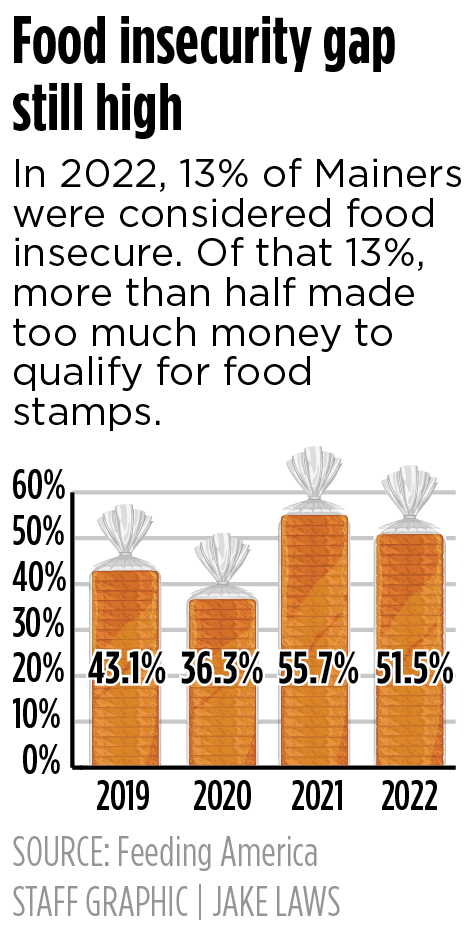

The number of people in Maine who don’t have enough to eat has been rising for years, but now new data shows that more than half of those considered food insecure don’t even qualify for food stamps, forcing more to rely on food banks to get by.

“It’s putting added stress on us in every way,” said Hopkins, the pantry’s executive director. “We want to make sure we have good, sufficient food available to people every week. We don’t want any family to go home with less than they need.”

So far, the pantry has been successful, but Hopkins acknowledges there will be ongoing challenges to sustain it.

Data from Feeding America’s new “Map the Meal Gap” survey reveals that food insecurity rates in Maine will increase from 10.5% in 2021 to 14% in 2022 (the most recent year for which data is available), resulting in an additional 35,000 people struggling to pay for food.

That means one in eight Mainers, including one in five children, are currently experiencing food insecurity, according to Good Shepherd Food Bank.

This is the highest rate of food insecurity in Maine since before the pandemic.

This effect is compounded by the widening gap between the number of people who need assistance and the number who actually receive it from the federal food stamp program.

Half of food-insecure Maine workers earn too much to qualify for Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, but not enough to put food on the table. The maximum annual income level to qualify for SNAP in Maine is $37,814 for a household of two and $67,673 for a household of five.

“This new data is shocking, but not surprising based on what we’re hearing from our community partners,” Good Shepherd President Heather Puckett said, referring to sharp increases in the prices of food and other essentials in 2022.

She said she expects food insecurity rates to rise even more in 2023 because pandemic-era SNAP benefits were cut early last year, further exacerbating the effects of inflation.

Good Shepherd Food Bank reported double-digit increases in both the number of visits and households served by its network of 600 food pantries in 2022 and 2023. The food bank expects to distribute about 40 million meals by the end of its fiscal year in June, up 19% from last year.

Puckett said Good Shepherd has expanded its distribution over the past decade, but “growing at this pace and continuing to distribute meals on this scale is not sustainable and is not the answer to building food security throughout our communities.”

Mary Jo Keenan bags donated bread at the Food Cupboard in South Portland. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Record number of pantries

About 185,000 Mainers were receiving SNAP benefits as of the end of April, up 6% from April of the previous year and up more than 11% since April 2022, according to the Department of Family Independence.

During the pandemic, Congress approved a temporary increase in SNAP benefits to help low-income individuals and families, averaging an additional $109 per person in Maine in 2022. Anti-hunger activists say the additional funding has been crucial for Mainers, allowing some recipients to buy all the groceries they need for the first time and reduce their reliance on food pantries.

When emergency benefits end in March 2023, Maine residents will see their monthly SNAP benefits reduced by at least $95 depending on the size of their household, a loss that is especially hard at a time when households are facing rising food, heating and housing costs.

Alice DiGiovanni organizes baked goods at the Food Cupboard in South Portland. As food insecurity rises in Maine, the number of people using food pantries has increased dramatically. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

According to the “Map the Meal Gap” study, the national average cost per meal has risen to $3.99, the highest it’s been in 20 years, even after adjusting for inflation. The average price per meal in Maine has risen to $4.19 in 2022.

But SNAP benefits don’t automatically increase when food costs rise (the last big increase was in 2021), so people often turn to food pantries to make up the shortfall.

“We hear a lot about rising costs and declining profits,” Hopkins said.

The South Portland pantry currently serves 140 to 180 families each week, some of whom travel from as far as Berwick to bring home 20 to 30 bags of food each month, and in some weeks, as many as a quarter of the families are using the pantry for the first time, Hopkins said.

Hopkins said the food pantry is on track to feed 23,000 people this year, up from 18,000 in 2023.

Dale Ashby, 70, of Portland, said he relies on the pantry to supplement the $1,048 in Social Security disability benefits and $230 in food stamps he receives each month. The groceries he takes home from the pantry make a big difference, he said.

“I go to Hannaford and what used to cost me $5 or $6 is now $9 or $10,” he said. “Without that subsidy, I would have to take it out of my check for $1,048. That’s a pretty tough situation.”

Pat Flaherty plates fiddleheads at a food shelf in South Portland. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Lisa Franklin, 52, of Portland, said her $1,595 a month in Social Security disability benefits leaves her little money left for groceries after paying rent and other bills. The $23 a month she receives from SNAP doesn’t even cover grocery store purchases, so she relies on food boxes from the Preble Street and Stroudwater Food Pantries for meat, milk and fresh vegetables.

“Honestly, I don’t know what I’d do without them,” said Franklin, a member of Voices for Homeless Justice, which has been advocating for increased funding to combat food insecurity in Augusta. “It’s unfortunate that some people have to rely on them, but they’re out there and it’s important that we support them in every way we can.”

Further support for children

The Maine Department of Health and Human Services also announced this week that Maine will be one of 37 states this summer offering the SUN Bucks program, which helps families obtain food for their children.

SUN Bucks (also known as the Summer Electronic Benefit Transfer Program) provides families with $120 per eligible school-age child to supplement their grocery budgets until school lunches resume in the fall. The USDA-funded program replaces Pandemic EBT, which was launched in 2020 to help families respond to the pandemic.

When the program launches in June, it will serve about 100,000 children in Maine.

Paula Baronas, right, and other volunteers work to distribute produce at the South Portland Food Shelf. Brianna Soukup/Staff Photographer

Most families are already enrolled in SNAP (Temporary Assistance for Needy Families) or an Indian reservation food stamp program, are homeless, are part of an immigrant family, or receive MaineCare with an annual income below 185% of the federal poverty level, and are automatically enrolled and therefore can receive SUN Bucks benefits without having to do anything.

Experts say this is a critical step to ensure children receive the meals they need over the summer.

“School is soon out for summer, which means Maine children will be missing their school breakfast and lunch,” Anna Corsen, policy and program director for Full Plate and Full Potential, said in a statement. “Thankfully, SUN Bucks will help fill that gap and augment families’ grocery budgets.”

Copy story link

Invalid username/password.

Please check your email to confirm and complete your registration.

To reset your password, please use the form below. After submitting your account email address, you will receive an email with a reset code.

” previous

Farmworkers protest Hannaford’s stance on ‘Milk with Dignity’ campaign

Next ”

Social Note: Spurwink values inclusivity

Related article