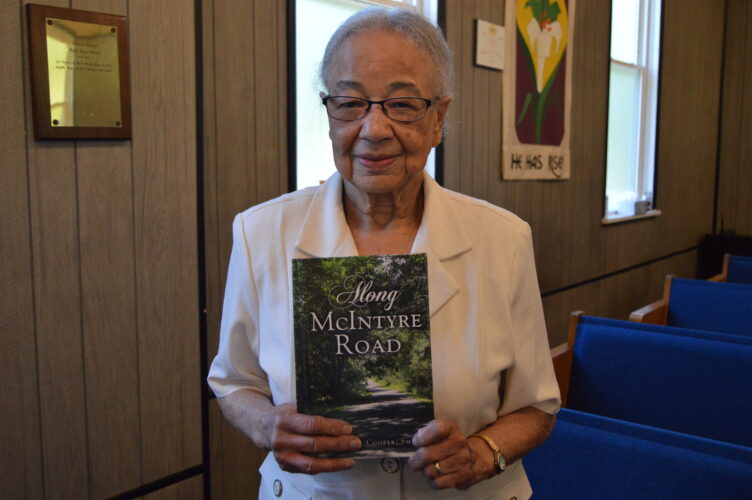

By Christopher Dacanay – Mary Ann Smith held up her book, “Along McIntyre Road,” which details her personal experiences living in a community founded in 1829 by freed slaves from Virginia.

WAYNE TOWNSHIP — More than three decades before the 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution declared that “neither slavery nor involuntary servitude shall exist under the United States, or any territory subject to its jurisdiction,” a group of African Americans who moved to Jefferson County were already granted a life of freedom.

McIntyre, an unincorporated community founded in 1829, occupies about 200 acres in Wayne Township, a region of rolling, wooded hills between Bloomingdale and Smithfield.

The community was originally founded by a group of freed slaves from Virginia and still exists today. The descendants of the original settlers are now scattered across the United States, but a few still live in the community, like 88-year-old Mary Ann Smith, who was born and raised in McIntyre and is passionate about its history.

McIntyre’s story begins with Nathaniel Benford, a planter in Charles City County, Virginia. In 1825, Benford freed seven slaves and their families and founded a colony near Sioux.

After his death, Benford freed nine more slaves and their families in his will: Paige Benford, Lee Carter, Collier and Fielding Christian, David Cooper, Ben Massenburg, William Toney, Fitzhugh Washington and Nathaniel Benford, who took his master’s name. Including women and children, the total number was 27, Smith said.

The company settled on land purchased by Smithfield resident Quaker Benjamin Ladd, who divided the land into plots for individual families. According to a 1989 paper by Frances Michelle Freeman, the great-great-granddaughter of freedman Nathaniel Bedford, the communities of Smithfield and Mount Pleasant were already known as refuges on the Underground Railroad.

Sources differ on the origin of the name McIntrye, with some saying it comes from McIntyre Creek and others that it comes from a man who supposedly helped freed slaves move there. Smith, whose Toney and Cooper families go back four or five generations, said the place was named for a Methodist bishop, many of whose members were freed slaves.

McIntyre is referred to as Haiti in some sources, including J.A. Caldwell’s 1880 book, History of Belmont and Jefferson Counties, but the name is perceived by some as offensive.

According to a 1900 letter published in C.A. Powell’s Journal of Negro History: Migration of Free Blacks to Ohio, 1815-1858, the settlers initially had difficulty adapting to their new land and tried to plant Virginia crops such as tobacco, flax and hemp. When that didn’t work, the settlers switched to corn, oats and rye to feed their livestock, and the remaining land was used as a market garden.

Powell describes the community’s subsequent development: “They have added to their land and built new cabins, but most of the old dwellings are still there and are inhabited by the descendants of the original settlers. Their numbers are rapidly increasing and they have intermarried extensively.”

Powell said religion was important to the settlers, and the first church services were held in homes before other accommodations were built. In 1920, Schaffer Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church was built and still stands today with an active membership. According to the church history, the church was named for the Rev. Cornelius T. Schaffer, an AME bishop and Civil War veteran at the time.

Smith said there have been several schools in the area over the years, including a one-room schoolhouse that served grades one through six and later the Oak Grove Schoolhouse, but people received their secondary education at the now-defunct Wayne Township High School.

Geographically, McIntyre is located on Town Road 191, known as McIntyre Road, which is the site of Shafer Chapel and across the street from Shafer Chapel Cemetery, the resting place of Civil War veterans, and includes a monument honoring the first male settlers.

Smith said the stone was taken from the original school building.

Smith himself lives a minute’s drive from Shafer Chapel on property on McIntyre Road adjacent to an old sign reading “Welcome to McIntyre” and “Established in 1829.”

After his father died in 2004 at age 96, Smith realized that his generation was “pretty much the only generation left around here.” With that in mind, he says, “The Lord inspired me to write something about life here,” to pass on the history of his beloved community to future generations.

She is now the author of “Along McIntyre Road,” which offers a personal perspective of growing up in the community and experiencing its early vibrancy. Written over the course of two years and officially released on June 9, the book is available digitally on Kindle and physically from Amazon and Barnes and Noble.

In the book, Smith details McIntyre’s Community Day celebrations, how Shaffer Chapel was “the center of everything,” the daily activities in the school building, holiday gatherings, and more. Oak Grove Park, established in 1958, hosted barbecues, plays about McIntyre history, and family reunions, bringing people from all places and races together in the community for a multi-day religious camp.

Smith said that when she was a student, McIntyre had more than 200 residents. There were concerned residents groups, police officers and even a community banner when the Jefferson County Fair was held in Smithfield.

But McIntyre has slowly changed and lost some of its former vitality, said Smith, the community’s oldest resident, with the population now “very thin” as the older generation has passed away and younger generations have sought opportunities elsewhere.

Still, McIntyre has not been forgotten. Smith spoke of a “Sunday surge” when people who live outside McIntyre return for the 11 a.m. service and close fellowship at Schaffer Chapel. People may have moved, but “they come whenever they can.”

So the latest Cooper family reunion took place last Saturday, bringing together people with McIntyre roots from all over.

“We’re telling our history. We’re trying to keep our traditions alive,” Smith said, noting this is the first reunion since the COVID-19 pandemic.

McIntyre may not be what it once was, but “there’s nothing to be ashamed of,” Smith said. He hopes that one day people will reinvest in the community and keep its history alive. With God’s blessing, things can change “in a blink of an eye,” Smith said.

“I believe in God. I believe that He has a provision. He tells us to walk by faith, not by sight. We just have to keep believing.”

Get the latest news from the day and more delivered to your inbox