Biologists at several start-up companies are applying cutting-edge genetic engineering techniques to the age-old problem of hair loss, creating new hair-forming cells that can restore a person’s ability to grow hair.

Some researchers told MIT Technology Review they’re using techniques to grow human hair cells in the lab or in animals: A startup called dNovo sent us a photo of a mouse with a dense clump of human hair growing out of it, which the company says is the result of transplanting human hair stem cells.

The company’s founder, Ernesto Lujan, a Stanford biology graduate, says his company can genetically “reprogram” normal cells, such as blood or fat cells, to produce the building blocks of hair follicles. More research is needed, but Lujan hopes the technology could eventually treat “the root cause of hair loss.”

This story is available to subscribers only.

Don’t be satisfied with half stories.

Get access to the latest tech news with no paywalls.

Subscribe now Already a subscriber? Sign in

We’re all born with our hair follicles, but aging, cancer, testosterone, genetic bad luck, and even COVID-19 can kill the hair-producing stem cells within them. And when the stem cells die, so does the hair. Lujan says his company can directly transform any cell into a hair stem cell by changing the pattern of genes that are active within the cell.

In biology, we have “come to understand cells as ‘states’ rather than fixed identities,” Lujan says, “and we can move cells from one state to another.”

Cellular reprogramming

The possibility of regrowing hair is part of a broader study into whether reprogramming techniques can overcome the symptoms of aging. In August, MIT Technology Review reported on Altos Labs, a secretive company that plans to study whether reprogramming can be used to make humans younger. Another startup, Conception, is looking to extend fertility by converting blood cells into human eggs.

A key breakthrough came in the early 2000s, when Japanese researchers came up with a simple formula for turning any kind of tissue into powerful stem cells similar to those in a fetus. Imaginations took flight, and scientists realized they could potentially manufacture limitless amounts of almost any kind of cell, including neural or cardiac cells.

But in practice, formulas for generating specific cell types can be elusive, plus there are problems with returning lab-grown cells to the body. So far, there have been only a few demonstrated cases of reprogramming as a way to treat patients: Japanese researchers have tried transplanting retinal cells into blind people, and last November, the US company Vertex Pharmaceuticals announced that it might have cured type 1 diabetes in men by injecting them with programmed beta cells that respond to insulin.

The concept the startup is pursuing is to take normal cells, such as skin cells, from a patient and convert them into hair-forming cells. In addition to dNovo, a company called Stemson (a portmanteau of “stem cell” and “Samsung”) has raised $22.5 million from investors including the pharmaceutical company AbbVie. Co-founder and CEO Jeff Hamilton says the company is implanting the reprogrammed cells into the skin of mice and pigs to test the technology.

Both Hamilton and Lujan believe there’s a sizable market: About half of men suffer from male pattern baldness, some starting as early as their 20s. When women lose their hair, it’s often more generalized thinning, but it’s still a blow to their self-image.

These companies are bringing high-tech biology to an industry known for fantasy. False claims abound, both about hair-loss treatments and the potential of stem cells. “People need to be wary of fraudulent offers,” Paul Knoeffler, a stem cell biologist at the University of California, Davis, wrote in November.

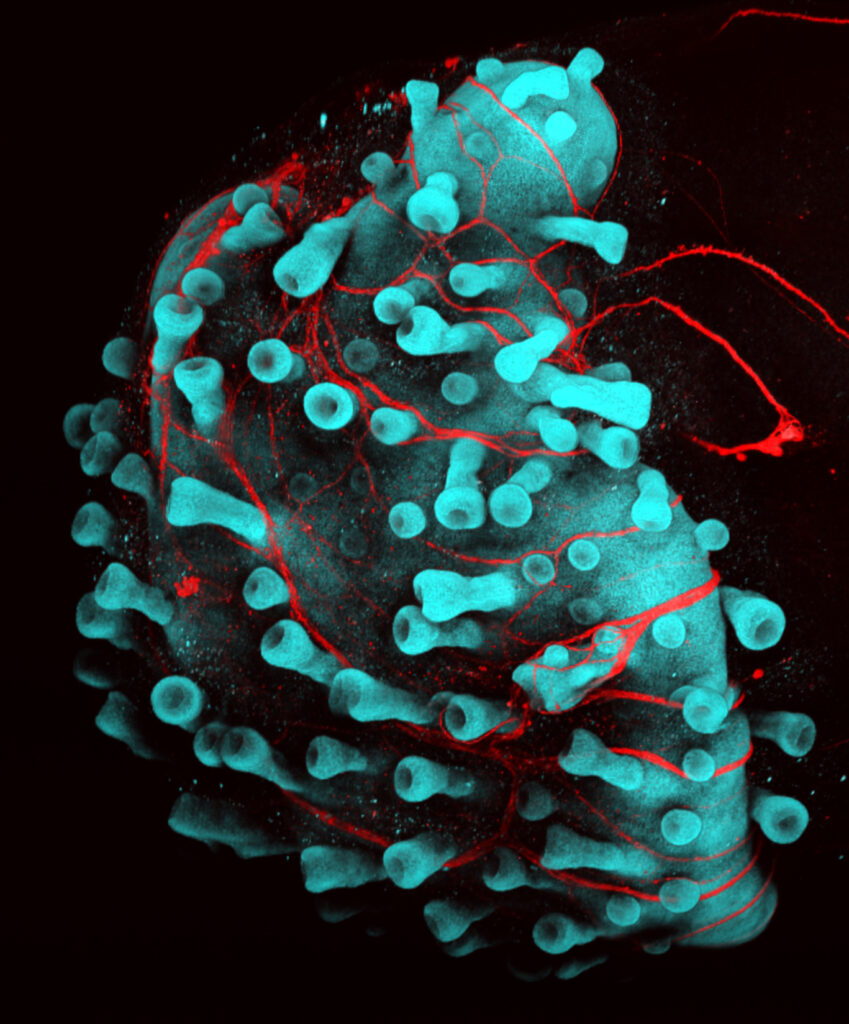

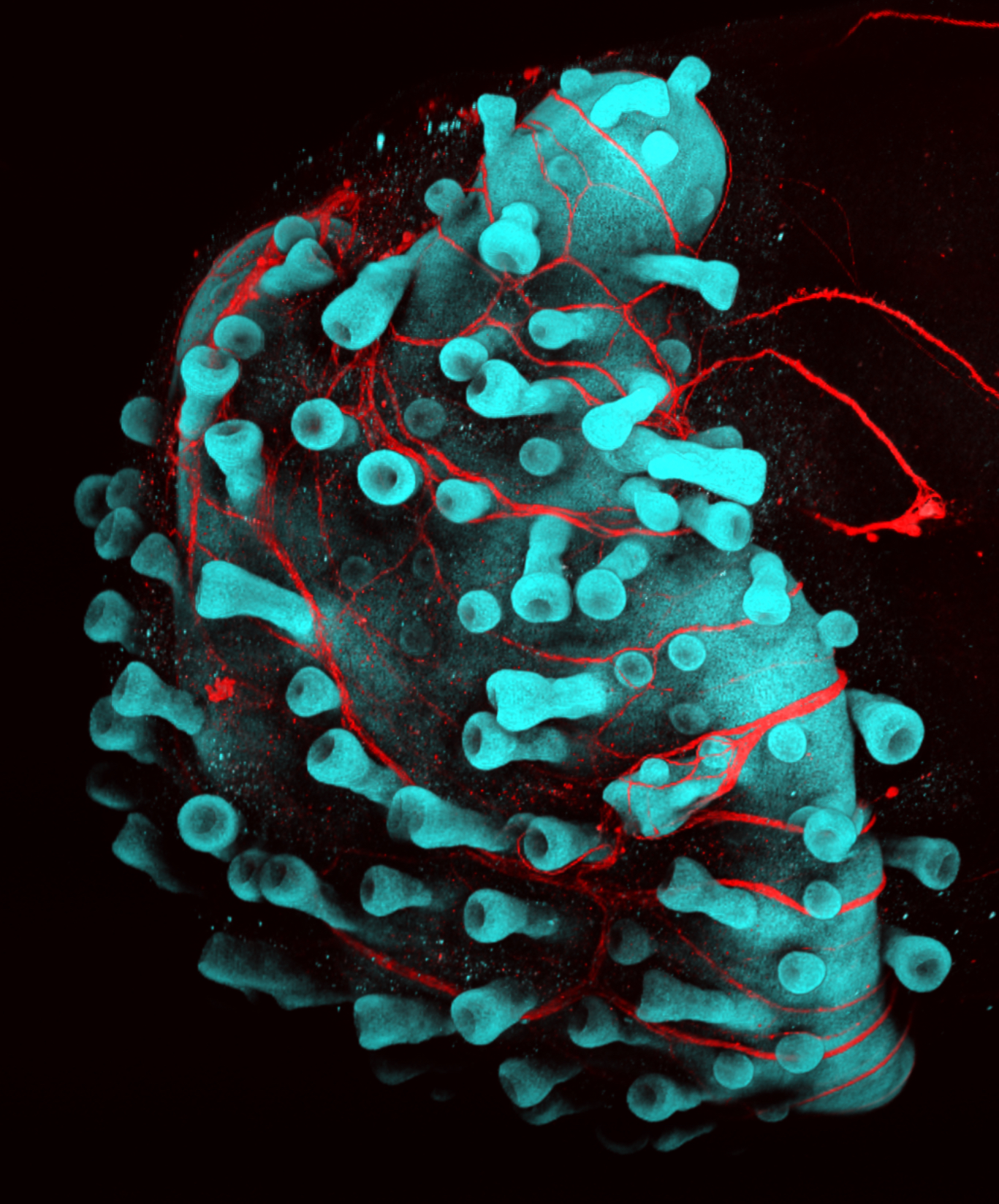

A close-up of a skin organoid covered with hair follicles.

A close-up of a skin organoid covered with hair follicles.

Jiyoon Lee and Karl Koehler, Harvard Medical School

Tough business

So is stem cell technology a cure for hair loss, or another false hope? Hamilton, who was invited to give a keynote speech at this year’s World Hair Loss Summit, said he was keen to stress that the company still has a long way to go. [people] “It’s common for scientists to come along and say they have a solution, and that happens a lot with hair, so I have to address it,” he says. “We’re trying to show the world that we are real scientists, and that the risks are so high that we can’t guarantee it will work.”

Currently, there are several approved drugs for hair loss, including Propecia and Rogaine, but their effectiveness is limited. Another treatment involves removing skin from an area that still has hair and surgically transplanting the hair follicles into the bald areas. Lujan says that in the future, it may be possible to transplant lab-grown hair-forming cells into a person’s head in a similar procedure.

“I think people will go to great lengths to get their hair back, but it will be a bespoke process at first and very costly,” said Karl Koehler, a professor at Harvard University.

Hair follicles are amazingly complex organs that arise from molecular interactions between several types of cells. Koehler says that photos of mice growing human hair are not new. “Whenever you see these images, there’s a trick to it, and something’s wrong with applying it to humans,” he says.

Koehler’s lab takes a completely different approach to growing hair shafts, by culturing organoids — tiny clumps of cells that self-organize in a petri dish. Koehler was originally researching treatments for hearing loss and wanted to grow hair-like cells from the inner ear. But his organoids ended up turning into skin, complete with hair follicles.

The accident prompted Koehler to create spherical skin organoids, which take about 150 days to grow and reach a diameter of about 2 millimeters, with clearly visible tubular hair follicles that correspond to the lanugo that covers a fetus, Koehler says.

One surprising thing is that the organoids grow backwards, with the hairs pointing inward. “You see these beautiful structures, but the big question is why they’re growing inside out,” Koehler says.

The Harvard lab is using reprogrammed cells taken from a 30-year-old Japanese man. But they’re also looking at cells from other donors to see if the organoids can lead to hair with unique colors and textures. “The demand is definitely there,” Koehler says. “Cosmetic companies are interested. When they see the organoids, their eyes light up.”