Grant Rooney Premium/Alamy

Grant Rooney Premium/Alamy

Is this a bad tourist summer? (Credit: GRANT ROONEY PREMIUM/Alamy)

From the destruction of ancient ruins to the disrespect of local cultures, inappropriate tourist behavior is becoming more and more visible — and ultimately, this may be a good thing.

It seems like every day around the world this summer, stories of bad tourist behavior are in the news.

It’s as if the whole world has forgotten how to behave in other people’s homes, and while this may seem like a summer of bad tourists, it might just represent an unpleasant truth: For as long as people have been traveling, we’ve been behaving badly.

Mark McConkey/Alamy

Mark McConkey/Alamy

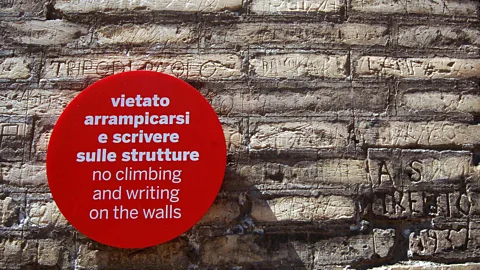

Many of Italy’s famous monuments have signs urging tourists not to damage them. (Photo by Mark McConkey/Alamy)

From Pompeii to the Egyptian pyramids, some of the world’s most famous man-made structures are marred by graffiti inscribed on their walls by tourists thousands of years ago. It’s no secret that many of the world’s greatest travelers, such as Christopher Columbus and Hernan Cortes, were also some of the worst travelers. According to Lauren A. Siegel, a professor of tourism and events at the University of Greenwich in London, until as recently as the 18th and 19th centuries, it was common for British aristocrats on Grand Tours of Europe to be contemptuous and dismissive of the people and places they visited.

What’s different this summer is that there are more stories about bad travelers. And this may ultimately be a good thing. With each new report of embarrassing, insensitive, or just plain rude behavior, our collective outrage seems to grow, and it may be reckoning time for bad travelers.

In a time of heightened awareness of entitlement and how we treat people from different cultures, the spotlight on entitled, uncouth travelers may seem like a natural extension of other recent social movements, but experts suggest a confluence of factors is behind both bad behavior abroad and the new attention it is drawing.

Unlike in the past, many travelers today compete for likes and views on social media, according to Siegel. “We’re seeing more people reverting to more extreme behaviors on Instagram and TikTok,” he said. Ironically, social media accounts like the wildly popular “Passenger Shaming” are also being used to call out insensitive and rude behavior.

ImagineChina Limited/Alamy

ImagineChina Limited/Alamy

Social media accounts are increasingly documenting the silly antics of tourists (Credit: Imaginechina Limited/Alamy)

David Bearman, an adjunct research fellow at the University of Technology Sydney, noted that about 1.5 billion people traveled internationally in 2019. With travel surging to its highest level since pre-pandemic, he said it’s inevitable that some tourists will think “it’s cool to pose naked in front of a temple in Bali, get drunk at an Islamic holy site or dance in front of a Nazi concentration camp”.

Gail Saltz, host of the “How Can I Help?” podcast, believes other factors are also at play, including “revenge travel” after years of pandemic lockdowns and anxiety. “People feel like they have a right to do now what I couldn’t do.” [during lockdown]and I can do them well enough,” she said. “They [foreign countries are] It’s a great party and you can do what you want.”

In particular, Saltz isn’t surprised by the number of people who have been caught inscribing their names on ancient monuments: “They see this as an opportunity to immortalize their names.”

But this summer’s embarrassing news may be an opportunity for change: every new crime is a reminder that traveling abroad is a privilege.

Nacho Calonge/Alamy

Nacho Calonge/Alamy

It’s not uncommon to see tourists taking selfies at the Holocaust Memorial in Berlin (Photo by Nacho Calonge/Alamy)

Nowhere has this essential truth been more apparent recently than in Hawaii. As the worst wildfires in modern US history ravage parts of Maui (one of the country’s most popular tourist destinations), thousands of beachgoers continue to fly in, with one local resident telling the BBC that the tourists are swimming in “the same waters where our people died three days ago.”

The great thing about traveling is that the wonders of the world seem even more amazing after we’ve visited them. We develop a deeper appreciation for what we know and are more inclined to protect it, or at least not destroy it.

The recent film Oppenheimer makes this point sharply. In one memorable scene, US Secretary of War Henry Stimson conspicuously excludes Kyoto from the list of cities to target for the atomic bomb. Japan’s ancient capital, with its temples and monasteries, was too precious to destroy. Stimson said he knew this because he had spent his honeymoon in Kyoto. The film makes it into a joke, but the message is true: we must not harm what is precious.

Rich Legge/Getty Images

Rich Legge/Getty Images

Kyoto was spared from the danger of the atomic bomb because the US Secretary of War was visiting Kyoto on his honeymoon (Photo by Rich Legge/Getty Images)

Some destinations are actively embracing the idea. Popular destinations like Bali and Iceland now ask tourists to formally promise to respect the culture and environment after their visit. Palau requires visitors to sign an eco-pledge upon arrival. Bucket list destinations are also tightening restrictions. Australia no longer allows tourists to climb Uluru (Ayers Rock) because it recognises it as a sacred Aboriginal site. Meanwhile, Amsterdam recently launched a “stay away” advertising campaign targeted at drunk Brits.

Siegel praised the stricter guidelines and said he sees greater awareness of the issue among his fellow travelers.

She points to an emerging trend on social media called “Instagram vs. reality,” where people purposefully show the behind-the-scenes congestion and chaos that is common at tourist destinations that influencers’ perfectly composed images and videos often omit.

Roger Coolum/Alamy

Roger Coolum/Alamy

Amsterdam is actively trying to discourage drunk Brits from visiting (Photo by Roger Coolum/Alamy)

And every time that happens, our earthly treasures become a little safer.

Larry Bleiberg is past president of the Society of American Travel Writers.