For over 100 years, Himler House stood on a hill overlooking Beauty, formerly Himlerville, in Martin County. Once the site of grand Christmas parties and banquets, the house was eventually abandoned and fell to ruins.

But few of the teens, vandals, and ghost hunters who frequented the abandoned mansion knew that it had been the center of a unique and radical experiment in Appalachian history: a cooperatively owned coal mine.

The Himler Coal Company, founded in 1918, was owned and operated by a group of predominantly Hungarian miners. The founder of the company was Martin Himler, a Jewish Hungarian immigrant who had arrived in New York in 1907 with 13 cents in his pocket.

Over the course of his life Himler mined coal, published a popular Hungarian-language newspaper, owned a series of businesses, and worked for the Office of Strategic Services arresting and interrogating Nazis in post-war Europe. He was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2021.

Himler House was built in 1919. It served as both Martin Himler’s private residence and a center of social activity for the town. Abandoned for decades, the building was disassembled in 2022. Many original materials and items were documented and preserved so the house can be rebuilt in the future. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University; Andrew Gess, 2024, courtesy of Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society)

Himler House was built in 1919. It served as both Martin Himler’s private residence and a center of social activity for the town. Abandoned for decades, the building was disassembled in 2022. Many original materials and items were documented and preserved so the house can be rebuilt in the future. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University; Andrew Gess, 2024, courtesy of Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society)

Himler’s house in Beauty, Kentucky, was disassembled in 2022 because it was structurally unsafe. But the house is at the center of the Martin County Historical Society’s efforts to preserve Martin Himler’s legacy and revitalize the town of Beauty in the process.

Cathy Corbin is the director of the Himler Project, a group made up of a mix of local government, civic and educational institutions. The group formed in 2014 after the Himler family brought a manuscript of Martin’s unpublished autobiography to the Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society. Corbin, a former English teacher, agreed to edit the manuscript and prepare it for publication. It was through this process that Corbin came to understand Himler’s significance.

“We realized there was a lot more to Martin Himler than just being an immigrant who came to America and mined coal,” Corbin said in an interview with the Daily Yonder.

Martin Himler at his newspaper publishing desk in 1940s Detroit. (Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society)

Martin Himler at his newspaper publishing desk in 1940s Detroit. (Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society)

One of the primary goals of the Himler Project is to rebuild Himler House and restore it to how it looked in the 1920s, when it was the social center of a thriving coal camp. To that end, Corbin submitted an application to have Himler House designated as a National Historic Landmark. The application is currently being considered by the National Park Service.

“It would be a tremendous economic boost to Martin County to have Himler House designated as a United States National Landmark and possibly Himlerville itself as a historic district,” Corbin said.

Himler Coal

Beauty is one of many former company towns in Eastern Kentucky. But it is not an exaggeration to say its history is wholly unique in Appalachian history, according to Briane Turley, a professor of history at West Virginia University and co-founder of the Appalachian-Hungarian Heritage Project.

Appalachian coal camps were notoriously exploitative. Miners were forced to rent their homes from the company at exorbitant prices, and the company store — the only business in town — used their own currency known as “scrip.” Other expenses, from miners’ equipment and uniforms to their transportation, were taken directly from their wages, creating a system of indentured servitude.

Martin Himler experienced this system firsthand shortly after his arrival to the United States. Born to a Jewish family in a small town called Pászto, Himler immigrated alone at the age of 18. With no contacts or resources besides a distant cousin, he accepted “free transportation” from New York to Thacker, West Virginia, to work in coal mines there.

Upon his arrival, he was informed that he owed $32 (around $1,200 in today’s dollars) for the costs of transportation and equipment. Together with the cost of room and board, and because Himler was not a very good coal miner, he expected to go months without any wages. After only eight days working in the mine, he abandoned most of his belongings and “skipped,” running away on foot to find better circumstances elsewhere.

“It was a form of slavery, and Himler understood that,” Turley told the Daily Yonder. “And he literally had to slip away in the dead of night. Otherwise, they would arrest him, have him dragged back into the camp and force him to work until he paid everything off.”

Himler later worked in another mine in Pennsylvania, along with stints doing everything from shoe cobbling to show business. But this experience in West Virginia’s coal mines was the basis for the eventual founding and operating of Himler Coal as a cooperative in 1918.

During the coalfield labor disputes of the 1920s, Himler Coal sought a middle way between unfettered exploitative capitalism and bloody battles for unionization. According to Turley, Himler was able to create his cooperative because he was a well-known and trusted presence in the Hungarian mining community, which was one of the largest immigrant groups in Appalachia at the time. This was in part due to his weekly newspaper, Magyar Bányázslap (Hungarian Miners’ Journal) which was circulated among Hungarian coal miners nationwide.

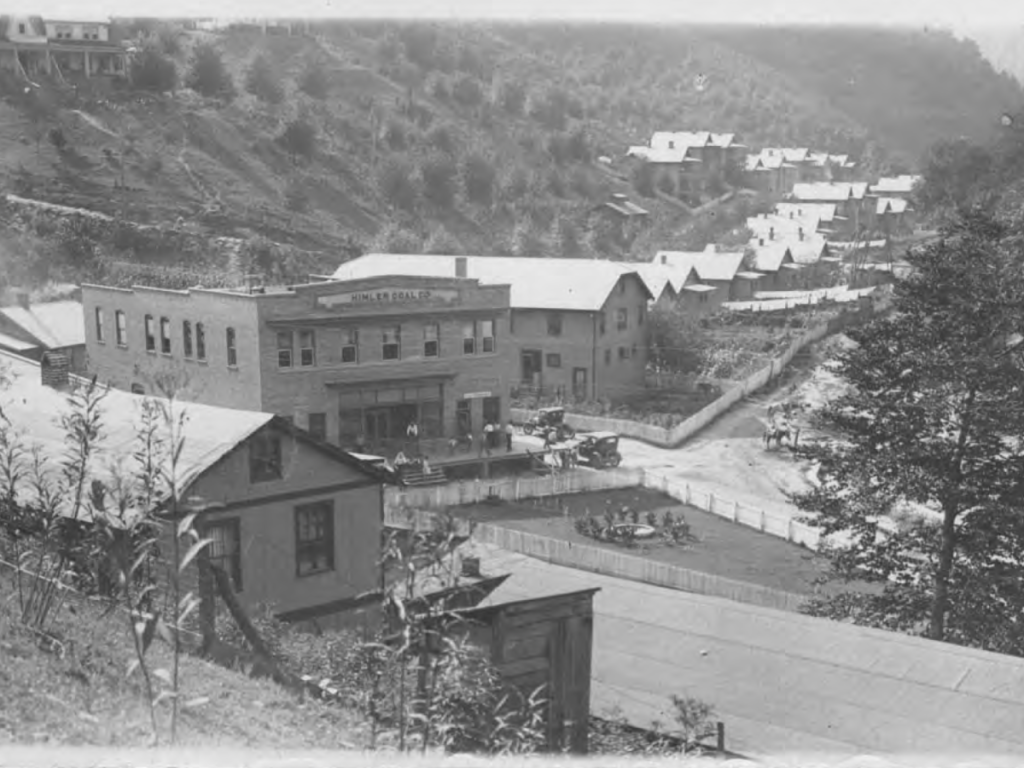

Himler Coal was the only known cooperatively-owned coal mine in Appalachia or anywhere else in the world. Martin Himler’s experience as a coal miner when he was a young man inspired him to pioneer a less exploitative alternative to standard mining corporations. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University)

Himler Coal was the only known cooperatively-owned coal mine in Appalachia or anywhere else in the world. Martin Himler’s experience as a coal miner when he was a young man inspired him to pioneer a less exploitative alternative to standard mining corporations. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University)

“Because he had experienced the worst environments of coal mining in Appalachia before unionization, he knew how difficult the work was and how unfair labor practices were among the corporations that ran the mine,” Turley explained. “The mining companies were out for a lucrative, quick profit.”

In contrast, the miners themselves were shareholders of Himler Coal and sat on the company’s governing board, an arrangement unheard of in Appalachia or elsewhere. Himler himself never owned more than 3% of shares, according to Turley.

Himlerville

Himler Coal’s unique structure was also reflected in its company town, Himlerville. Unlike standard coal camps, Himlerville’s miners owned their own houses. Himler also did away with the oppressive “scrip” system at the company store.

“The company stores in most of Appalachia were terrorist organizations. You either purchased from them or you didn’t survive,” said Turley. “But there it was just one of many stores. You could go someplace else.”

Himlerville was known for its relative luxury. Each house had electricity and indoor plumbing, which was almost unheard of in Appalachian coal camps in those days.

In his autobiography, Himler writes that his personal objective in developing Himlerville was “to raise the standard of living of my people in every respect. My people were encouraged to live up to the standard in their modern and much-appreciated homes, and visiting Americans were astounded to see coal miners eating off white tablecloths and using white napkins.”

More than 100 miners’ homes were built in Himlerville in the 1920s. The town was lively; social events included movies twice a week, lectures on European and American history, and shows and dances put on by a 24-piece brass band. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University)

More than 100 miners’ homes were built in Himlerville in the 1920s. The town was lively; social events included movies twice a week, lectures on European and American history, and shows and dances put on by a 24-piece brass band. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University)

Himler also put great emphasis on education. The local school was soon rated the top school in the state of Kentucky. And because such a large percentage of miners and residents were Hungarian, the school was bilingual. Himler also considered Himlerville to be a great Americanization project and organized a night school to teach civics and prepare miners to become U.S. citizens.

According to the Himler House’s registration form for the National Register of Historic Houses, Himlerville was found to be the nation’s second most livable coal town by the U.S. Coal Commission.

“One of my miners told me that life on the camp would have been paradise were it not for the mine,” Himler wrote in his autobiography. “And he was right.”

Of course, Himlerville was not free from controversy. The Hungarian press was divided on Himler’s exploits – he was too conservative for the Left and far too radical for conservatives. Additionally, there was often tension between American-born Appalachians and Hungarian immigrants in Martin County. Linguistic and cultural differences played their part, as did nativism and negative stereotyping on both sides.

Martin Himler and his nephew, Andrew Fisher, on the scaffolding of the Himler Coal Company Store. Privately-owned homes and a non-exclusive company store made Himlerville unlike any other coal camp in the region. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University)

Martin Himler and his nephew, Andrew Fisher, on the scaffolding of the Himler Coal Company Store. Privately-owned homes and a non-exclusive company store made Himlerville unlike any other coal camp in the region. (George Gunnoe Papers, Marshall University)

But like so many American utopian experiments, Himlerville would prove to be short-lived. After World War I, the coal industry fell into a depression. Supply continued to increase as mines got more efficient, but without the demand driven by the war, prices fell steeply. Like many coal companies in the 1920s, Himler Coal could not survive the downturn in the market and the company struggled financially. A devastating flood in 1928 marked the end of an era. Himler Coal went bankrupt and Himler and most of his miners left the town.

Preserving legacy

Today, nearly 30 original miners’ homes are still standing and in use in Beauty, along with the original Himler Coal company bank, powerhouse, railroad bridge, and Hungarian Cemetery.

Himler House was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991, but the Martin County Historical Society is aiming to upgrade that status to a National Historic Landmark — a much rarer designation that indicates national significance. The Historical Society also hopes that the rest of Himlerville could eventually be declared a National Historic District. The National Historic Landmark application for Himler House is currently under review.

“Each of these sites are very important to Martin County and to Eastern Kentucky,” said Corbin. “If the house does receive National Landmark designation, this is a tremendous asset for this area of Appalachia, which has been hit hard by lack of coal mining.”

The Himler Project’s goals go beyond rebuilding and restoring the house itself. Celebrating Himlerville’s history and legacy has become an international affair, with Hungarian musicians and scholars participating in cultural and scholarly exchanges in Appalachia.

The Historical Society hopes to develop a museum, and potentially add a restaurant and event space to make the house into a destination for school field trips and tourism alike. Himler’s later work interrogating Nazis for the Office of Strategic Services makes him a local entry point for Holocaust history, a topic that is mandatory in Kentucky public schools. Some other ideas to generate tourist traffic include adding Beauty to a National Scenic Byway like the Coal Heritage Trail, or connecting it physically to a network of local hiking trails.

But historical preservation is never a cheap proposition, especially in the case of a house that has to be rebuilt from its foundations. Charlotte Anderson, president of the Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society, said funding is the biggest obstacle.

The project is estimated to cost nearly $1.9 million dollars, and in one of the poorest counties in Kentucky, that kind of funding is hard to come by. The Historical Society puts on a number of annual fundraisers, selling Polish sausages, sweets, and soup beans at various events.

“One of our board members is somewhat famous in our area for his soup beans, so that’s a big fundraiser for us. Now, when I say big, I mean a thousand dollars or so. That’s about as much as we get at any one time,” Anderson said. “It’s been a slow process, trying to come up with things in order to make the money to get at it.”

Jim Hamos is Martin Himler’s great-great-nephew, and one of several family members involved in the Himler Project. He worries that Beauty is too inaccessible to attract much out-of-state tourism.

Today Beauty is an unincorporated town in Martin County with a population of around 900 people. (Photo by Andrew Gess, 2024, courtesy of Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society)

Today Beauty is an unincorporated town in Martin County with a population of around 900 people. (Photo by Andrew Gess, 2024, courtesy of Martin County Historical and Genealogical Society)

“I don’t know how many people will make that sort of trek. It’s one thing when you’re off an interstate highway, but it’s another thing when you’re so remote” Hamos said in an interview with the Daily Yonder. “I find it really interesting. But how it becomes someplace where lots of people will go and pay money, I don’t know. But I’m hopeful.”

The National Parks Service lists tax incentives, access to grants, and assistance with preservation as some of the key benefits of National Historic Landmark status. Corbin is hopeful that such a designation will give the Himler Project the support they need to rebuild Himler House and manage the site as a tourist destination.

In the meantime, Hamos, who was himself a refugee during the Hungarian Revolution, takes inspiration from the lessons that can be learned from Himlerville.

“I’m thrilled that the people of Martin County want to do this. They’re trying to claim a piece of their history,” Hamos said. “I do believe this country is a family of immigrants. So I think that’s what we should be continuing to accept in this country.”

This story is republished from The Daily Yonder under a Creative Commons license.