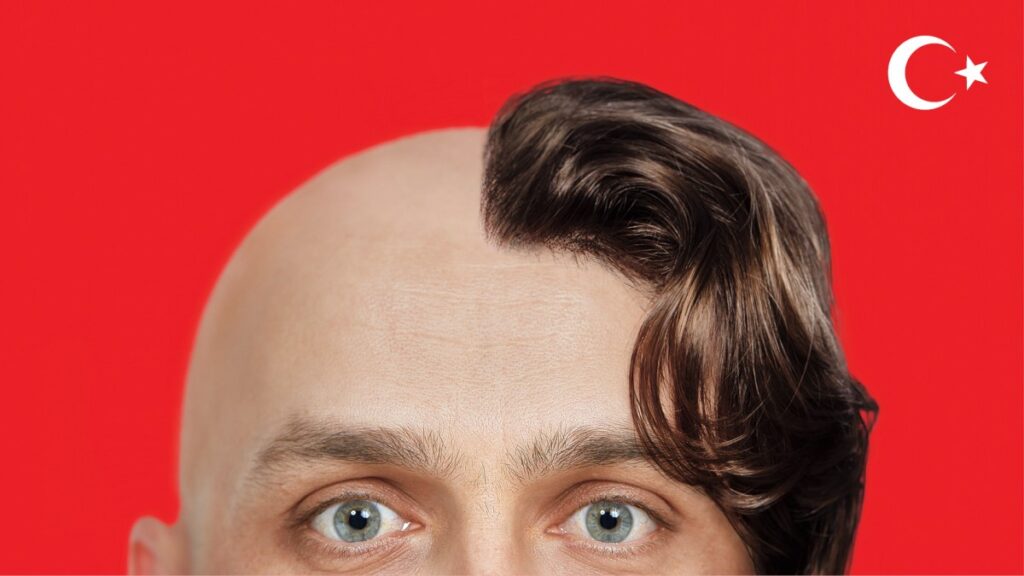

Two days after his hair transplant Mahmoud Yassine, a 23-year-old software developer from Oxford, stands in the courtyard of Istanbul’s Blue Mosque wincing at the bloodied and bandaged new hairlines of a group of men sitting nearby.

“It looks so red,” he says, his own newly scabbing dome glinting in the sun, a pressure band wrapped tight around his forehead. “They must have just had it done.”

Since he had the operation Mahmoud has been sleeping propped up on a travel pillow, trying to avoid disturbing the 3,800 grafts of his hair and beard that have been extracted and implanted onto the top of his head in a pleasingly irregular pattern to mimic natural hair growth.

He wanted to have the transplant to boost his confidence and avoid that moment at the barbers when, as his hair was combed back, he’d realise how little there was left.

“The top of my head, I haven’t shaved that in about two years,” he says. “When I go to the hairdresser he does the side but doesn’t touch the top.”

His mum and sister thought the operation was a good idea. Saleh, his dad, who has been balding since his late thirties, said if it had been available when he was younger he would have had it done.

So Mahmoud went for it. He booked a flight to Istanbul and lay sedated in an operating theatre for seven and a half hours while a team of six Turkish medical staff surgically intervened to reverse the hand that genetics had dealt him. It cost him £2,790, including a three-day stay in a four-star hotel. In the UK he could expect to pay at least three times that.

Mahmoud Yassine, from Oxford, has a consultation with Dr Serkan Aygin in Istanbul

JOHN BECK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

For the entirety of human history men — and some women — have experienced hair loss. Many men hit their thirties or forties and suddenly find they look like their dad. Until about a decade ago, for most people there was no way of avoiding it. Now you can solve the problem for the price of an all-inclusive holiday. Of course you look rather odd for eight months or so afterwards. Transplant surgery starts with the extraction of hair follicles from a donor site, often the sides and back of one’s head, where even most bald men have hair. The hair grafts are inserted into tiny incisions in the scalp, often causing minute pustules to form around the hair follicle. These then heal and typically shed the hair, leaving the area as bald as it was before. After a few more months they start to regrow, finely at first, like baby hair — known as the “ugly duckling” stage — before thickening. Then, there is hair. Your own hair, moved, graft by graft, from one part of your head to another.

• Never mind my Botox, what about Louis Theroux’s brows?

Doctors have been working towards this point for centuries. In 1822, in the German town of Wurzburg, the medical student Johann Friedrich Dieffenbach published a paper describing the experimental surgery he had performed with his mentor, Professor Dom Unger: transplanting hair from one part of the scalp to another. It didn’t catch on. In Japan in the 1930s, the dermatologist Dr Shoji Okuda pioneered a technique for the transplantation of grafts. Yet few outside the country were to hear of it.

It was a paper published in 1959 by Norman Orentreich, a New York dermatologist, that sparked the modern phenomenon. He established the principle of “donor dominance”, demonstrating that transplanted hair retains the characteristics from its original location, and laid down the technique for surgical transplantation. Slowly, the knowledge spread. Yet until the 1990s the procedure was still the preserve of the vain and the rich. Turkish doctors were the first to realise the money-spinning potential of scaling up their operations and putting a full head of hair within the price range of the working and middle classes. Fifteen years ago techniques were still developing: strip harvesting, which is pretty much as it sounds like — a strip of skin is removed, split into grafts and implanted, the wound sewn up — started to be edged out by follicular unit extraction (FUE), in which individual grafts containing several follicles of hair are excised and implanted elsewhere. Blocky hair “plugs” were refined into a more natural-looking hairline.

Turkey was already a centre of medical tourism for the Arab world. Highly trained doctors, relaxed visa requirements and competitive prices kick-started its transplantation industry. Soon Europeans with Middle Eastern and Turkish backgrounds were coming in larger numbers. They told their friends.

Over the past five years the industry has exploded. According to the head of the Turkish Health Tourism Association, about one million people came to Turkey for hair transplants in 2022, creating more than £1.5 billion in revenue.

Last month Rio Ferdinand, 45, revealed he had travelled to the city for a hair and beard transplant. In an advert for a clinic, the former England footballer said, “Listen, if you’re ever thinking about getting yours done, this is the place to be.”

Istanbul, the city of seven hills and jewel of the Ottoman Empire, is now the world capital of hair transplants. You see the patients everywhere. Walking down Istiklal Caddesi, the main shopping street, with their scalps still red raw and yellow stains creeping from the edges of their bandages. At the shopping centre, at the bus station and at the airport you can see why the hashtag #turkishhairlines has had four million views on TikTok.

The hashtag #turkishhairlines has had four million views on TikTok

@IEDEMIRAYAK / X

They are builders, doctors, architects and plumbers, often dressed in the oversized bucket hats that are the only headgear you can wear for the first few days. They are film stars (who never seem to go bald any more) and your next-door neighbour who has, now that you come to think of it, a strangely even-looking hairline.

And it is also a huge business, targeted at male anxieties about lost youth. If you google, as I have done, “hair transplant Istanbul” a couple of times, the algorithm fills your feed with a stream of adverts in which normal-looking blokes in their thirties are given new locks with the hairline and density of a Lego figurine.

For less than £3,000 a balding man can fly to Istanbul, get picked up in a limousine, stay in a four-star hotel, go on a Bosphorus cruise, visit the Hagia Sophia and — ideally — level up their dating prospects. They can bring their wives and buy a couple’s deal where he gets new hair and she has a “mummy makeover” — nipping and tucking her birth-ravaged body under general anaesthetic until she looks like the Venus de Milo. Or they can bring their mums for new teeth and a touch of Botox. Some get their blood taken, spun in a centrifuge and injected back into their scalp to (reportedly) stimulate hair growth.

The football pundit Rio Ferdinand had a hair and beard transplant in Istanbul last month

@RAFSENAL / X

All these things and more are available at Dr Serkan Aygin’s clinic in the grey district of Sisli on the European side of Istanbul. On the day before his operation Mahmoud sits in the consultation room looking slightly nervous as a doctor draws a dotted line onto the sparsely populated part of his scalp where his hairline once was.

The clinic looks like an upmarket PR agency (a quarter of its 400 staff work in the marketing department), with a coffee bar, multilingual staff, tasteful lighting and a lot of expensive-looking modern art. Resting on the sofas in the corridors are dozens of men with bandaged heads, most of whom look as though they’re in their late thirties.

Mahmoud arrived last night with his father and sister. Before flying over he’d sent photos of his head to the clinic and was reassured that he was a good candidate for a transplant.

Now Aygin tells him they’ll be able to make about 3,800 grafts, most of which will fill in the front of his hairline. When a donor graft is extracted it never regrows, so the number of follicles that are available to harvest depends on how much hair there is at the donor site — take too much and there is a risk of scars, patches and blank spots. Afterwards Mahmoud will be given anti-balding medication. Later he might be able to come back for more implants to his crown.

Harvested follicles will form a new hairline

JOHN BECK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

The clinic does 20 transplants a day, six days a week, working from 7am to at least 9pm, with two shifts of staff — mostly nurses, though a doctor will supervise the operations. Aygin has offices from London to Miami and there are plans to open more, with backing from the Turkish government, which heavily subsidises the hair transplant industry. Rival operations have started in other countries including Hungary and Thailand, often poaching Turkish experts, but no city is close to taking the crown from Istanbul.

“This clinic is making a really big investment in hair transplant, in techniques, in education, in marketing,” Aygin says. “We are doing these operations in the perfect place, really.”

Aygin, a dermatologist with 22 years’ experience in the Turkish hair transplant industry, has turned this clinic into a highly successful enterprise. At the start his patients were mostly Turkish. Now they come from Europe — Italians like to go on lads’ trips, with six or seven friends in a group — and Arab countries, with some clients from the US and Asia. About 10 per cent are from the UK. They are aged between 22 and 85, though most are in their mid-thirties. One 83-year-old Italian patient recently came for his third operation.

Aygin has the air of an extremely rich man who has had his foibles indulged for decades without question. His perfectly smooth face bears the hallmarks of plastic surgery and he has a habit of rubbing people’s backs and trying to hug them even when they snap “stop touching me” (hi).

He insists that clients come to his clinic not because it’s cheap but because it provides a high-quality service. “It’s not about money,” he says. “No, please don’t focus on the money. Focus on what’s going on here, what’s the result, why are they coming here.”

Nurses prepare some of the 3,800 grafts

JOHN BECK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

He argues that emphasising how cheap the procedure is in Turkey or asking whether it’s performed safely misses the point, which is that hair transplants will soon become normalised the world over, with more clinics opening everywhere, including the UK.

His patients, though, say that the price is a big reason why they come to Turkey. The equivalent procedure in Britain would cost about £9,000-12,000 — well out of reach for many. Still, some are nervous about coming to Turkey because of stories about “transplants gone wrong” and testimonials online showing scarring and infections after budget operations.

There do appear to be some very bad hair transplant clinics in Turkey. I’ve seen some terrible examples where the front has been filled in but the hair on the dome has then fallen out, leaving a youthful hairline at the front and a bald circle on the back.

Greg Williams, vice-president of the British Association of Hair Restoration Surgery (BAHRS), says that while there are risks to having a hair transplant, they are very rarely life-threatening. “There have been a few publicised deaths from hair transplants in Turkey, but not many,” he says. “So really, what you’re talking about here is aesthetic disfigurement from poorly done hair transplants.”

• Tom Cruise’s mop: the hair that says ‘I win’

Williams, who performs hair transplants in the UK, advises patients to find out from a clinic exactly who will be doing the transplant, and whether they are a doctor, a technician or a nurse, before handing over any money. They should also discuss with the doctor what will happen if something goes wrong and who will follow up with them — and make sure that the people treating them speak English.

Under Turkish law, doctors have to make the incisions in the scalp during the hair transplant. “Doctors should do the cutting of the skin and generally that’s not what happens in Turkey,” he says, later adding: “You’re having invasive surgery done by non-doctors with, in theory, a doctor supervising. Whether or not that supervision is in the room or in the building varies from clinic to clinic.”

The grafts are implanted in a seven-hour procedure

JOHN BECK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

Those considering travelling to Turkey should, he says, check the online advice provided by BAHRS and the International Society of Hair Restoration Surgery.

While there are good surgeons in Turkey the industry is still poorly regulated, Williams says. “I’ve personally never seen a great transplant come back from Turkey. I’ve seen lots of what you might argue are good results. And especially from a patient’s perspective, they’re pleased. But they may come to me to finesse the result to make it look natural.”

He adds: “I have no issue whatsoever with people going to Turkey. I just want them to be aware of what they’re getting themselves into. If you’re told that a non-doctor is going to operate on you and you’re happy, I’ve got no beef with that.”

Regulations are becoming more strict in Turkey, making it harder for new clinics to open and existing ones to dodge the law. If things go wrong it can also be incredibly difficult to make a medical malpractice claim in Turkey, says Ali Guden, a British-Turkish lawyer working in Istanbul and London, particularly against the cheaper clinics, which might not have insurance.

“The patients need to be careful when they’re choosing their clinics,” he says. “If it’s not a good hospital, it will be very difficult to sue them.”

Mahmoud just wants to have a bit more hair. On the day of the operation he’s nervous. Parts of his head are shaved. Then he is sedated, given a local anaesthetic (the most painful part, he later says) and the extraction begins. It’s both fascinating and repulsive to watch. A nurse wearing magnifying glasses uses a “punch” to remove tiny grafts from Mahmoud’s beard and the sides of his head, wiping away the blood as she goes. Each stub of hair has a grey, gluey piece of skin stuck to the bottom and is placed on a tray to be sorted by how many follicles it contains.

After a break for lunch (“Quite a bit of dizziness,” Mahmoud says) the implantation starts. The nurses spray the grafts to keep them supple and place them one by one inside the implanter pens, which they then jab into the top of the Mahmoud’s head, moving with the nimble fingers of people who have done this thousands of times.

Post-op patients wear pressure bands in a courtyard at the Blue Mosque in Istanbul

JOHN BECK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

The average operation takes six to eight hours and involves thousands of grafts implanted by a team of at least six people, mostly nurses, and someone who supervises the local anaesthesia and sedation (patients are not given a general anaesthetic). A doctor might check the progress and make a few insertions themselves.

As Aygin points out, at this scale it is not possible for a doctor to do all this by themselves. Especially if you are paying less than £3,000. While showing me around he repeatedly calls the woman implanting the hair into Mahmoud’s head “Dr Meryem”. Which is news to her and her colleagues, who say she’s a nurse with many years of experience.

“You are focusing on the wrong things, really,” he chides me when I bring up whether doctors are involved in the procedures. “You need to understand that in Turkey we are implanting 5,000 grafts [in one procedure]. Can you imagine 5,000 grafts done by just doctors? Where would you find such a doctor?”

Twenty years ago, if you were balding and unhappy about it you could just avoid looking in the mirror. But with social media, online dating and Zoom calls, we’re assaulted by proof of our changing appearance every day. Many of the doctors I interview point to the Love Island effect — how the idea of a perfect hairline, perfect tan, abs and teeth has become the norm.

This trend has been exacerbated by clinics that bombard potential patients with adverts on social media. Constantinos Dimitriou, 40, an actor from Cyprus who moved to Southend last year with his British husband, came for a hair transplant at the Micro Fue Turkey clinic in Istanbul because he wanted to continue getting work in an industry that thrives off youth and beauty.

Prior to going on stage or appearing in front of the cameras, he used to spend hours on his hair — styling it in different ways and using a hair-fibre spray to give the illusion of thickness.

“I want to get back as much hair as possible so I can stop using different ways of hiding my issue,” Constantinos says in his hotel room in Sisli, the day after the eight-hour operation. “It’s really important. Someone might say, ‘Oh, this is just you being vain. Get on with it. Just deal with it.’ But no, it’s not that easy.”

Mahmoud’s new hairline the day after surgery

JOHN BECK FOR THE SUNDAY TIMES MAGAZINE

So far he is thrilled with the results. But what happens after a few years? Matthew, who lives on the outskirts of London and works in the film industry, had a hair transplant in Turkey four years ago. He was 28 and single, and had started to go bald at the front, his widow’s peak creeping ever backwards. He found that in the shallow world of online dating, being a balding man in his twenties was a disadvantage. He looked at himself. He looked at his (bald) dad. And he got on a flight to Istanbul.

“It wasn’t the most rational thing. I was sort of feeling anxious about it and feeling as though I had to do something,” he says. After a year his hair looked good. Now it’s thinning again: this time at the back, while at the front his hairline is still that of a 25-year-old. He’ll soon have to make a decision: either shave his head or go back to have another transplant.

Looking back on his trip, he wishes he’d thought more about why he actually wanted to get it done — not just jumped on a plane as a snap reaction to ageing and insecurity about his looks.

“In your twenties it’s just so stressful and it feels like the most urgent thing in the world,” he says. “And now it doesn’t quite feel that way. Lots of guys are really rubbish at talking about this kind of thing. It’s a lot easier to try to find a solution than, you know, admit anxieties about ageing, and looking ugly — and not getting a date.”