Chicago History Museum, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and 1970s”/Photo: Chicago History Museum

The term protest art conjures vivid images: splashes of color in the form of mass-painted banners, screen-printed T-shirts dotted with expressive pins, and handmade signs, as well as the repressive monochromatic uniforms of rows of punitive police officers. Today, it’s the green, red, black, and white of the Palestinian flag that animates our city and university buildings, but the Chicago History Museum’s current exhibition, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and ’70s,” reminds us that colorful, creative energy has long been used for social and political change.

Chicago History Museum, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and 1970s”/Photo: Chicago History Museum

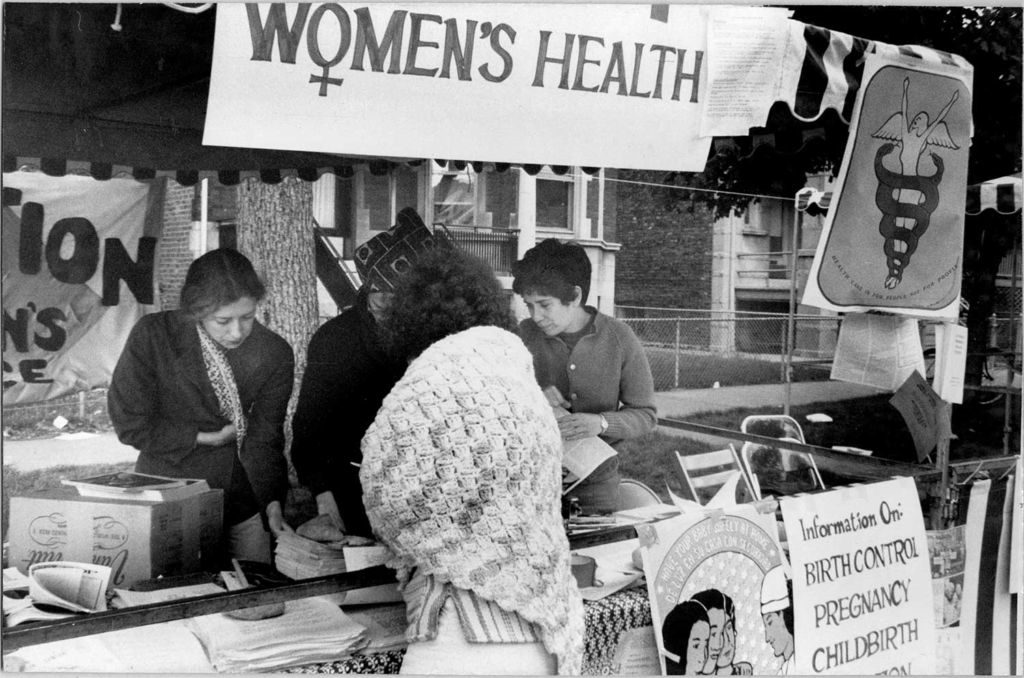

The exhibition’s interconnected themes showcase two decades of social activism in Chicago through artistic practices deployed for causes. Fragments of events from long ago, such as flyers and posters created for charity shows and poetry readings, are displayed alongside history lessons such as Ellis Books of African American Literature and the legendary Mountain Moving Coffee House for lesbians and women. These locations served as cultural hubs for Chicagoans for many years. Mimicking the rise of identity politics and the various struggles that took place in the city during this contentious period in history, including civil rights, black power, the gay and lesbian liberation movement, and women’s liberation, the exhibition encompasses a wide range of artworks that make good use of the definition of protest art.

Chicago History Museum, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and 1970s”/Photo: Chicago History Museum

From flags and symbols used in the Chicago Freedom Movement to paintings and linograph prints by artists working as part of the Black Power movement, the first section of the exhibition focuses on the use of visual culture in black life, tracing the transition from symbolic works intended to convey meaning to others to the creation of artworks intended to speak to those in the black community. In particular, the works in the second section are filled with striking images that show resolute unity. Whether it be Barbara Jones Hoag’s 1971 work “Unite (AfriCOBRA),” a depiction of a group of people holding black power fists in the air above which the word “unity” is repeated like a resounding cry, or Margaret Burroughs’ 1970 linocut print of Phyllis Whitley, the first African-American poet to publish poetry, the message is one of historical and continuing collective power.

Chicago History Museum, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and 1970s”/Photo: Chicago History Museum

Anti-Vietnam War art reads like a lesson in repurposing, the use of images from mainstream culture for subversive purposes. In one example, a banner used by the Yippies at the infamous 1968 Democratic National Convention used dollar bill eyes and pyramids to proclaim “NOW,” as in “End the War Now.” The banner is placed above a flyer distributed by the Weather Underground, a radical group that split off from the Students for a Democratic Society. The flyer read in bold letters, “Bring the War Home!”, urging people to bring the war to Chicago and confront the police on what the group calls “Days of Rage.” In another, the cover of Seed, a Chicago magazine that best illustrates repurposing, exposes the hypocrisy of police and politicians. The video quotes the police chief as saying, “These bombings are the insane acts of psychopaths,” a clear reference to the actions of the Weather Underground, but contrasts it with depictions of US warplanes bombing peaceful farmers in Vietnamese fields, reflecting the heinous actions of the elites rather than the people fighting to end the war.

Chicago History Museum, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and 1970s”/Photo: Chicago History Museum

Many of the issues addressed in the exhibition are still relevant today. Take, for example, a print by artist and environmental activist Estelle Carroll. In her work, titled Late than You Think (1972), a gear-like clock ticks across a desert landscape. Its minute and hour hands are made of hungry crows and the shadow of what appears to be the last tree, a surrealist image that gets to the heart of the environmental issue. Nearby, another of her prints, a red-and-purple poster, takes a more direct approach. It reads: “Abortion is a personal decision, not a legal debate.”

Chicago History Museum, “Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and 1970s”/Photo: Chicago History Museum

It’s eerie to see anti-war protest flyers, which could have been written and distributed yesterday, on display in the glass galleries of a history museum, recalling the view of museums as cultural graveyards, institutions dedicated to presenting a bygone era to the general public. Yet far from diluting the artistic strategies and passionate concerns of its creators, the exhibition breathes new life into Chicago’s tradition of resistance to power. It is fitting, then, that the exhibition ends with a small collection of current works that are taking up the mantle of protest art for a new generation.

“Designing for Change: Chicago Protest Art of the 1960s and ’70s” will be on display at the Chicago History Museum, 1601 North Clark, through May 2025.