Last August, as the 2023-24 school year began, the Arkansas Department of Education announced that a pilot AP African American Studies course would no longer count toward state graduation requirements. The reason? The state said the course potentially violated a new law, championed by Gov. Sarah Sanders, that banned “indoctrination” and the teaching of “critical race theory” in the classroom.

In the end, the six Arkansas high schools that offered the pilot class last year kept doing so, but the move set off a firestorm of national criticism. It also sent a clear message to Arkansas teachers and schools: Tread carefully when discussing race. Speak too harshly about the country’s brutal past, and you could break the law.

But the recent maelstrom over AP African American Studies is only the latest chapter in the story of how Black history has been taught in our state. For me, it recalled memories of childhood — of my first forays into reading and of courting the praise of my evocative, culturally enigmatic teacher with the funny name, Ms. Igwe.

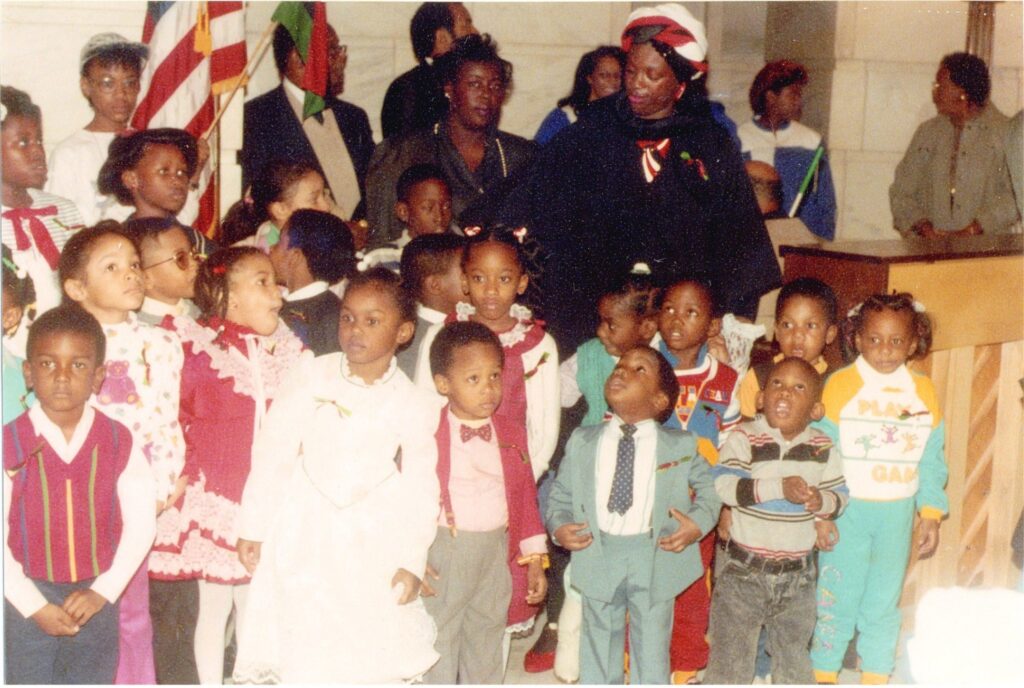

Forty years ago, an Afrocentric school here in Little Rock introduced hundreds of young Black students and their families to a new way of approaching history and education. Students from preschool through sixth grade were instructed in the traditional subjects in a manner that centered the impact and achievements of African people across the globe. They were also exposed to the legacy of this country’s discrimination against those people and the guile and resilience deployed to resist and survive it.

Sanders might call that indoctrination; others would call it American history.

Patricia Washington McGraw opened the McGraw Learning Institute on Jan. 2, 1983, in a converted grocery store near the corner of 13th and Pulaski streets. The school initially had six students, including McGraw’s grandson and two cousins. Interest in the program quickly swelled: Six years later, the school had expanded to 86 students, with a waiting list of 212. Classes of no more than 10 each were taught by pairs of teachers.

McGraw believed in the potential of a student demographic routinely maligned for the nation’s stubborn achievement gap. A little over 25 years earlier, Little Rock had become a symbol of the struggle to integrate American classrooms when nine Black students entered Central High School with the federal government’s backing, despite the efforts of then-Gov. Orval Faubus and a mob of white Arkansans to prevent “race mixing” in the city’s schools. In the decades that followed, Central Arkansas’s efforts to remedy segregation — from busing to creating magnet schools — routinely privileged the retention of white students, rather than enacting specific measures to address educational disparities and help Black children.

I started preschool at McGraw in 1988 at age 4. Though I was a student there for only one year, it had a profound impact on my life. It was at McGraw that I became aware of my Blackness and how it was perceived. The school introduced me to the importance of achievement, both for myself and my community. If there was a need to trumpet one’s cultural identity in order to engender pride, then McGraw made us children aware of that need and fashioned our voices to do so.

VISIONARY: Patricia Washington McGraw. Credit: Courtesy Arkansas Black Hall of Fame

VISIONARY: Patricia Washington McGraw. Credit: Courtesy Arkansas Black Hall of Fame

From Wash U to preschool

Patricia McGraw was born in 1935 in Little Rock and received her diploma from the segregated Dunbar High School in 1953. Denied admission to the University of Arkansas at Little Rock (then called Little Rock University) because of her race, McGraw studied at Spelman College in Atlanta for a year before going on to obtain a bachelor’s degree in language arts in 1957 and a master’s degree in American literature, both from San Francisco State College in California.

McGraw began her teaching career in Little Rock in the 1960s at Philander Smith College, eventually becoming chair of the school’s humanities division. She became the first Black professor at UA Little Rock in 1969 when she began teaching there part time. In 1972, she was awarded a National Endowment for the Humanities grant that allowed her to traverse the state for a year, visiting Arkansas schools and churches to lecture on Black history. In 1974, she joined the faculty at UA Little Rock full time.

She taught at the college level for more than 20 years before earning a doctorate in sociolinguistics and Black studies from Washington University in St. Louis in 1982. She opened the McGraw Learning Institute the next year.

It was not the first time Black Arkansans had started a school in response to discrimination in the era of integration. In 1970, three “boycott schools” were founded in three different communities: the College Station Freedom School in Pulaski County, in response to an unjust busing plan; the Black Movement School, in Wabbaseka, in response to the firing of Black teachers; and the Soul Institute of Earle, founded to protest racist practices in the local school district. All were short-lived, but all grew out of the same rambunctious spirit that responded to the establishment of private, white academies by organizing schools of one’s own.

The institute founded by McGraw in 1983 proved to be longer lasting.

Always a believer in the innate ability of young children, McGraw encouraged students to learn at an accelerated pace. “We were still in the mindset that some stuff was too advanced for 2½-year-olds,” Rhonda Bell Holmes, whose child attended the school, recalled. “[McGraw] said these 2½-year-olds must be potty-trained and they will be sitting at a desk learning. When they started coming home with spelling lists at 3 years old, I was like, ‘It’s a baby. They can’t spell all this.’ So she had to help us. All kids can learn what you present to them.”

The McGraw school was a kind of salve against the resentment I and others would unavoidably grow to feel when we realized that our success in the public schools was an afterthought, the result of “criminal indifference.”

Former McGraw students remember the emphasis she put on presentation and performance, her love of language and storytelling. Each day at McGraw began with a school-wide recitation of the poem, “I Am the Black Child” by Mychal Wynn.

Ryan Davis, a Little Rock activist and the head of UA Little Rock’s Children International, attended McGraw as a third-grader. “The primary mode of Afrocentric expression in the school was really just to center everything Black … especially Africa and African antiquity,” he remembers. “[There was] a lot of emphasis on how wonderful Black people truly have been, even under what we currently deal with. I hear people say there’s no ‘Black’ way to teach math, but in a school like McGraw, there was a purposeful connection made that disconnected everything from whiteness.”

For example, students learned that algebra was an invention of the Muslim world, Davis recalled. “Saying, ‘Algebra is Arabic,’ is not Afrocentric, but it’s a purposeful decentering of whiteness.”

ALUM: Ryan Davis (at lectern) attended the McGraw school as a child. Credit: Brian Chilson

ALUM: Ryan Davis (at lectern) attended the McGraw school as a child. Credit: Brian Chilson

Students were introduced to West African culture and geography through dance and drumming. The school placed particular emphasis on public presentation, with students either sitting rapt before performances from local dramatists like Curtis Tate or marveling at and mimicking Dr. McGraw’s own precise, elegant diction.

T.J. Hendrix, now an educator at Thurgood Marshall Academy Public Charter High School in Washington, D.C., attended McGraw from the third through the fifth grades. She said her dance class, taught by Sha’Ron Igwe, provided the most salient connection to Afrocentricity.

“Miss Igwe was our dance instructor and she would teach us dance that was African-inspired. She would teach us about the different cultures and tribes in Africa, and so dance class wasn’t just dance. It was also like history,” Hendrix said.

Children also absorbed African history in the classroom. “I learned about Shaka Zulu, and I learned about Nefertiti. … I learned African geography, and I learned about revolutionaries like Nat Turner and Toussaint Louverture. I learned about all these people that my classmates in public school didn’t even know about,” Hendrix said. The early experience gave her “a deep sense of understanding about what it meant to be Black” that continued into middle school and beyond, she said.

Ruby Steward-Brown, an instructor at McGraw from 1991 to 1994, said the school’s teachers themselves were educated by Patricia McGraw. “[Martin Luther] King was about all we knew [of important Black American figures] at that time — until we met Dr. McGraw and we learned about other leaders [like] Harriet Tubman and Bass Reeves,” she said.

When it came to discipline, McGraw emphasized positivity. “She based everything on positivity and knowing more about ourselves as Black people,” Steward-Brown said.

WHOLE KID EDUCATION: Khiela Holmes (front left, in gray shirt) with other children at a family reunion, including fellow McGraw students. Credit: Courtesy Rhonda Bell Holmes

WHOLE KID EDUCATION: Khiela Holmes (front left, in gray shirt) with other children at a family reunion, including fellow McGraw students. Credit: Courtesy Rhonda Bell Holmes

‘We teach our children … how beautiful they are’

The McGraw Learning Institute developed at a moment when Afrocentric ideas and iconography were enjoying a resurgence in American culture. Ryan Davis remembers the mid-’80s as a heady time in Little Rock’s Black community.

“I don’t think it’s acknowledged as much, but Black parents were experiencing a reawakening around Afrocentricity,” Davis said. “So independent Black schools were kind of en vogue. You saw everything from folks wearing the leather Africa medallions to hip hop having this moment of Afrocentric expression.”

Longtime literacy advocate and community organizer Patrick Oliver remembers this spike in interest as spurring him to open “Images of Africa” in the early ’90s — a shop on Main Street selling books, clothing and art themed toward connecting African Americans to their past.

“Spike Lee movies were out, particularly Malcolm X. So we had all the ‘My Brother’ T-shirts and the ‘Sisterhood’ T-shirts … All that was happening, not just in the Black community in Little Rock, but all over the United States,” Oliver said. “Everybody was celebrating Black unity and Black art. And they were wearing it.”

At the same time, intellectuals such as Temple University’s Molefi Asante were developing theories of Afrocentrism — an effort to intentionally center Black history and culture. These national trends filtered back to Little Rock, informing local discourse and creating communal networks. Oliver recalls McGraw coming into the store, introducing herself and inviting him to come and do a presentation on his store’s collection for her students.

Khiela Holmes, the daughter of Rhonda Bell Holmes, doesn’t attribute the founding of the McGraw school to a “super-scholarly understanding of Afrocentrism. I think it was just this understanding that Black kids being around other Black kids and being taught by Black people is very likely a good thing.”

Khiela Holmes. Credit: Brian Chilson

Khiela Holmes. Credit: Brian Chilson

Holmes, a clinical psychologist practicing in Little Rock, said such an environment encourages you “to remember who you are, to have a positive sense of your African heritage, despite any negative images you might see and experience in other places.”

By 1988, the McGraw Learning Institute was drawing attention beyond Little Rock’s Black community. The Associated Press wrote a story on the school — still available on the Los Angeles Times’ website — calling it “the only black private school in Little Rock.” (The school remained private throughout its existence, with families contributing $2,650 annually for the year-round program.)

McGraw told reporter James Jefferson that opening the school was a “necessity.”

“For about 20 years I’ve taught on the college level, and it has been my experience that many Black students do not use the language well, even after 12 years of schooling,” she said. “They do not feel good about themselves and generally . . . most of them need something that has been lacking in the school systems.”

She told the Arkansas Gazette something similar in 1991. “The reason our school is important in this world is because we teach our children from day one how beautiful they are,” McGraw said. “In this country many times Black children are not taught some basic things to make them feel good about themselves.”

Black educators felt “proud that a place like McGraw existed in Little Rock,” Steward-Brown said. “The model that she had going on was fantastic. When those students started going out to the other schools, you could tell — it was like a halo over their heads. They were already ahead, sort of like a Montessori style. You could tell they came from McGraw.”

I learned African geography, and I learned about revolutionaries like Nat Turner and Toussaint Louverture. I learned about all these people that my classmates in public school didn’t even know about.

T. J. Hendrix

Like its founder, the school led a nomadic life. From its original location near the corner of 13th and Pulaski, McGraw moved to a two-story building at 10th Street and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Drive. The school moved next to the campus of Liberty Hill Baptist Church at 1205 S. Schiller St., then landed at 5906 W. 53rd St. in Southwest Little Rock in 1991.

The McGraw Learning Institute closed in 1994 after 11 years and hundreds of students. “Great ideas and initiatives sometimes run their course,” said Lori McGraw Baker, McGraw’s daughter, on why the school shuttered.

McGraw returned to teaching at the University of Central Arkansas, continued writing and performing, and published the novel “Hush! Hush! Somebody’s Calling My Name” in 2000. She retired from UCA that same year. She now lives in Dallas with her daughter.

A place for Blackness in schools

I only attended McGraw for one year. But I wonder if that early influence helped make me the writer I am today.

Did I learn of the importance of storytelling there? Was the importance of performance imprinted there? Did I develop some early awareness that Blackness wasn’t a thing to be eschewed but celebrated? And that there was a value in knowing to draw from that identity some sense of pride or motivation?

Integrated schools in America provide little space for processing cultural vestiges of resentment. As a Black man who was educated in public schools, I’ve long resented the amount of effort expended to attract white students to remain in the classroom with me. And I’ve resented the fact that private academies were created so that those uncomfortable with my presence didn’t have to go to school with me.

With an air of bitter inevitability, James Baldwin said, “To be a Negro in this country and to be relatively conscious is to be in a state of rage almost all of the time. And part of the rage is this: It isn’t only what is happening to you. But it’s what’s happening all around you and all of the time in the face of the most extraordinary and criminal indifference, indifference of most white people in this country, and their ignorance.”

It is that anger, presumably, that prompts powerful white politicians to try to prevent AP African-American Studies from being taught in schools: They fear how Black students — and others — will react to a deeper understanding of the country’s shameful past.

But I believe the McGraw school was a kind of salve against the resentment I and others would unavoidably grow to feel when we realized that our success in the public schools was an afterthought, the result of “criminal indifference.” Beneath Patricia McGraw’s performative air was a woman with enough nerve to create a space where my growth and development were the institution’s paramount aim.

Perhaps McGraw awakened within me some desire to see a publicly funded institution that sets about addressing centuries-old issues of racial injustice. A public school classroom could be that venue, encouraging students to begin the dialogue of truth and reconciliation America has barely stuttered through since Reconstruction.

Two decades ago, I and other Black classmates at Little Rock’s Central High petitioned against the elevation of European and American History into AP courses as long as contributions of people of color around the world went disregarded, angered by the subtext of white supremacy. Today, at last, the College Board has created an AP course that gives African American history its due. I now hope to see that anger being given space in more public school settings, and I hope students are taught to reapply that resentment to an academic pursuit.

It appears the state has lost momentum in its effort to marginalize AP African American Studies. Now that it is no longer a pilot program, the state Department of Education has said the course will be treated like other AP courses in the coming school year. And, in the face of a federal lawsuit filed by Central High students, teachers and parents, state officials have effectively retreated on the state law that prohibits “indoctrination” and “critical race theory” in the classroom.

African American Studies may produce feelings of anger, bitterness or shame in both Black and white students. But such negative reactions are only the beginning. Teaching students to harness their feelings and deploy them toward productive means could reveal a radically mature method of processing historical trauma. Rather than ignoring the painful history of our nation and our state, schools should help students understand the past, acknowledge their feelings, and set their passion and drive toward the pursuit of a better future.