Summary

Turkey-Africa relations have evolved to an unprecedented level in economic, political, cultural and security terms.

Turkey’s Africa policy constitutes one foreign policy instrument for Turkey’s prevailing status-seeking in world politics.

The emphasis on ‘ownership’ and ‘equality’ reinforces the sustainability of Turkey’s African policy.

The complex historical relations between North African countries and the Ottoman empire continue to impact North Africans’ perceptions of Turkey negatively as compared to Sub-Saharan Africans’ perceptions, which are relatively positive.

African authorities have an opportunity to leverage their relations with Turkey to their advantage and should unify their capacities towards this and be more open towards Turkey.

Executive Summary

As a continent long neglected in the Turkish foreign policy agenda, Africa has increasingly become a new niche diplomacy area where Ankara’s broader strategic outlook has made considerable progress. Turkey offers an alternative partnership modality to African countries, one informed by a tailor-made strategy associated with its anti-imperial and non-colonial ideology towards the continent. Its Africa policy constitutes one of the new niche diplomacy areas for its foreign policy and a source for its prevailing status-seeking policies in world politics. Turkey’s activities in Africa have concentrated on five main areas: economy, military, development and humanitarian cooperation, culture and education and religion. Among these five issue areas, the three first policy fields appear more strategic than the rest, making Turkey a unique actor on the continent.

Turkey does not position itself as a rival to the other major players on the African scene, such as the USA, UK, France, Nordic countries, China, India, Russia and Japan. Its autonomous actorship in Africa also strengthens its hand and helps Ankara differentiate itself from the continent’s former colonial powers as a partner without any imperial ideology or colonial baggage. Its strategic and diplomatic pull in Africa is informed by a non-interventionist and sovereignty-centred approach to international politics. The commonalities between the African and the Turkish worldviews of the changing international order and continuous global inequalities are striking, with both sides seeking reform in the existing global governance architecture.

Although Turkish aid towards Africa is minimal compared to that of other development cooperation actors on the continent, it creates an immediate and visible impact on the daily lives of Africans at the micro-level. Turkey has tended to position its aid policy as the ‘Turkish way’ of development cooperation based on what is called ‘the Ankara consensus’, which is an alternative model of development cooperation to those contained in the Washington consensus and the Beijing consensus. For Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), most Turkish funds have gone to Muslim-majority countries, some with Ottoman-era connections such as Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan. Turkey provides only grants to African countries, with no place for loans. This is one of the aspects that differentiates Turkey from both traditional donors such as the EU and emerging donors such as China. Turkey provides all of its official development assistance (ODA) to the continent through bilateral channels and with aid primarily directed towards social and economic infrastructures.

Between 2020 and 2021, out of the top ten trading partners of Turkey in Africa, five were from North Africa and the other five from SSA, located mainly in the western, eastern and southern parts of the region. Of those ten trading partners, only South Africa, Nigeria and Algeria maintained a positive trade gap with Turkey successively in 2020 and 2021. In defence and military relations, Turkey, benefiting from its non-colonial past on the continent, has started to increase its activities in the field of security, ranging from its involvement in the state-building process of Somalia to its military presence on the continent with the establishment of its first military base in Somalia in 2017. More recently, it intensified its arms sales to Africa and its drone diplomacy. Turkey’s arms sales to Africa are far less than those of the largest exporters of arms to Africa who are, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Russia, USA, China and France; Turkey currently contributes only 0.5% to Africa’s arms imports from outside the continent.

Most African countries see Turkey as a rising donor and trading partner that at least appears to care about African needs by pursuing a balanced strategy between its interests and African needs. However, North African perceptions about Turkey differ slightly from SSA perceptions since Turkey has deeper historical ties inherited from the Ottoman Empire era with all North African countries.

Background

As a continent long neglected in the Turkish foreign policy agenda, Africa has increasingly become part of Ankara’s broader strategic outlook. Since the country first launched its African Action Plan in 1998, Turkey-Africa relations have taken a new path, especially during the first decade of the new millennium, which saw a gradual institutionalisation of bilateral relations. The most notable effect of this Plan is the Turkey Africa Partnership Summit, which has been held every five years since 2008.

During the Cold War, Turkey had a western-oriented foreign policy and distanced itself from the non-aligned movement and third-worldist discourses, which complicated its efforts to reach a rapprochement with African countries. However, despite its limited presence in Africa during the Cold War, Turkey’s relations on the continent, once they picked up, took a pragmatic approach, as seen in Ankara’s attempt to rally support among the United Nations’ African member states on the Cyprus issue.[1] Turkey’s “reset” with Africa gained momentum in 2005 with Ankara’s declaration of that year as the “year of Africa” and in 2008 with Turkey’s admission to the African Union as a strategic partner. Since then, Turkey has recalibrated its approach to relating with the continent, creating partnerships with African regional organisations such as ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States) and SADC (Southern African Development Community) and has recently shown its support for the new African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA). Ankara’s deepened mutual engagement with Africa since the 2000s includes, but is not limited to, the increasing diplomatic, cultural and trade priorities of the African countries that have opened and continue to open new embassies and consulates in Turkey.

Despite the recent economic downturn and the uncertainties, Ankara has used input from its relevant government departments to craft a roadmap for African engagement. Nevertheless, Turkish development and humanitarian aid towards Africa are modest compared to other foreign actors on the continent. In addition, the negative effects of the coronavirus pandemic, Turkey’s current economic difficulties and the growing geopolitical uncertainties in its regional neighbourhood raise crucial questions about Ankara’s ability to implement a more ambitious, effective policy agenda with African countries.

Given this background, this policy paper aims to outline what a holistic and more realistic approach to Turkey-Africa engagements could look like by focusing on multiple dimensions of this relationship, including development aid, trade and investment and defence and security policies. It also highlights African perceptions of Turkey’s presence on the continent and provides future projections of the relationship’s sustainability.

To this end, this paper makes use of a mix of methodologies including both quantitative and qualitative data. We conducted interviews with African diplomats in Turkey, with Turkish diplomats and with African students and businessmen based in Turkey. We also relied on statistics from secondary sources, mainly official web sites (OECD, Turkish Statistical Institute, SIPRI, World Bank Integrated Trade Solutions) and relevant academic papers. The statistical analysis, mostly for the mainstream data, generally covers the period from 2015 to 2020, with some analysis covering the periods 2021 and 2022 depending on data availability.

1. Turkey’s Engagement in Africa: Strategic areas and discourses

Turkey’s activities in Africa have concentrated on five main areas: economy, military, development and humanitarian cooperation, culture and education and religion. Among these five issue areas, the first three appear as more strategic. However, in the field of culture and education, Turkey also follows a long-term multidimensional policy aiming to boost its status as a “partner in need” for African countries and expand its sphere of influence in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In the religious arena, a complex network of Turkish religious associations acting on the ground makes it difficult for Turkey’s Directorate of Religious Affairs to use its religious influence as a soft power instrument effectively. The multiplicity of Turkish religious associations in the culture and education sphere may also negatively affect Turkey’s state capacity to implement its African policy agenda as the unique representative of the country’s religious affairs in Africa. On the other hand, in recent years, Turkey has been increasing its African footprint in military and defence sectors. But its current ascendancy in Africa is linked more to its rising donor status than to its trading-state role as a business partner and arms exporter to the continent.

Another important characteristic of Turkey’s strategic roadmap in Africa is its pragmatic discourse informed by a win-win approach to bilateral relations. As stated by Elif Çomoğlu Ülgen, General Director of West and South Africa in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, during an interview we held with him, Turkey’s tailor-made strategy associated with its anti-imperial and non-colonial ideology makes it a unique actor on the continent. Ülgen added that this uniqueness also derives from the fact that Turkey does not position itself as a rival to the other major players on the African scene such as the USA, UK, France, Nordic countries, China, India, Russia and Japan. Ülgen underlined how Turkey does not have any counter strategies or an alternative plan to weaken Africa’s relations with other major actors. The country sees its increasing influence in Africa as a result of its neutral stance towards African policy and its embedded African policy centred on a “mutual understanding of needs and gains”.

Another important aspect of Turkey’s African policy is its non-intervention in the rapidly changing African domestic policy landscape. The Turkish government prefers collaborating with the actual governments rather than with oppositional groups and prefers adopting a neutral stance in cases of domestic conflicts. This approach is illustrated in the crisis between the Ethiopian Government and the Tigray Rebels, where Turkey has tried to maintain a neutral position by voicing that it is in contact with both sides to exhort them to enter into negotiations and peace talks. According to some policymakers in Ankara who were interviewed as part of this research, Turkey’s neutral stance towards changing African domestic policy also helps it build its strategic leverage on the continent. Its strategic and diplomatic pull in Africa is informed by a sovereignty-centred approach to international politics. Indeed, Turkish policymakers’ voice-raising and criticism of the unjust decision-making mechanisms of the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) and the dominance of Western powers in the Bretton Woods institutions also harmonise with African leaders’ critical discourses on the existing global governance architecture and the Western-centred international system.[2] In short, the commonalities between the African and the Turkish worldviews of the changing international order and continuous global inequalities are striking, with both sides seeking reform to the UN system.

Of importance is also that, in the first ten years of the Turkey-Africa rapprochement, from 2005 to 2015, Turkey prioritised its development cooperation with Africa over its economic and cultural-educational concerns. The clearest illustration of this trend was Turkey’s much-appreciated humanitarian footprint and activism in Somalia amidst the hunger crisis in 2011: the role played by Turkey in Somalia has contributed to enhancing Turkey’s identity as a humanitarian actor in Africa and to increasing its activism in humanitarian and development aid throughout Africa. However, the development aid Turkey disbursed to Africa over that period remained modest compared to that of other actors actively engaged on the continent in recent years. Development cooperation has gradually become a new niche diplomacy area where Turkey can boost its visibility and recognition internationally. In this regard, Turkey’s African footprint is attributed to its new role as a “rising donor”, which is backed by its proactive and humanitarian diplomacy discourse. In 2019, 2020 and 2021, Turkey reached the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) official development assistance (ODA) threshold of 0.70% of gross national income by providing, respectively, 1.15%, 1.14% and 1.00% of its gross national income to ODA.

In recent years, Turkey has started to structure its Africa policy along more institutionalised lines, which has helped Ankara’s relations with the continent go beyond development cooperation and towards a more strategically oriented and interest-based partnership. This approach is exemplified by the fact that Turkey’s humanitarian diplomacy in Somalia has paid off in material terms, with Turkish companies such as Albayrak and Favori being prioritised by the Somali government in the procurement of big infrastructure projects, the airport renovation and management and the port management, to name a few. In discourse and literature, the Turkey-African foreign policy relationship is portrayed as mutually inclusive and effective, especially considering the short time frame. The African leaders we interviewed stated how, even though Turkey has a relatively modest development aid budget compared to that of major powers, its aid seems to have delivered “good” results in terms of efficiency and to be including a wide range of actors from government to Turkish private non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and local African NGOs.

Another important feature of Turkey’s Africa strategy is that it has not been built on an aid-for-trade rationale. As Ülgen underlined during our interview, Turkish aid towards Africa is minimal compared to that of other actors on the continent. However, it creates an immediate and visible impact on the daily life of Africans at the micro-level, such as the distribution of food packages to poor people during Ramadan, the building of schools in poor and neglected regions, the organisation of collective cataract surgery for African people, etc. Furthermore, more than 98% of Turkish aid has been delivered via bilateral channels, rather than through multilateral aid channels. Turkey’s autonomous actorship in Africa also strengthens its hand, which, in turn, helps Ankara promote its positive distinctiveness as a partner without any imperial ideology or colonial baggage.

2. Turkey’s Rise in Africa: Terms and scale

Addressing the questions relevant to the specificities of Turkish-Africa engagement requires critical data-based analysis of the terms and scales of Turkey’s engagements and their meaning for Africa. This section starts by providing information on Turkey’s aid policy towards Africa. It then continues by looking at economic engagement before turning to defence sector aspects.

2.1. Aid

Turkey has tended to position its aid policy as the ‘Turkish way’ of development cooperation based on what is called ‘the Ankara consensus’, an alternative model of development cooperation to the USA’s Washington consensus and the Chinese Beijing consensus. Table 1 showcases that, between 2015 and 2020, SSA received substantially more of Turkey’s ODA disbursement than did North Africa (NA). However, in total, the percentage of Turkish aid going to Africa has declined. The fall of SSA’s share in Turkey’s ODA is striking because the share fell continuously from 9.66% in 2015 to 0.71% in 2020. For NA, where aid flow was considerably lower, the percentage has fluctuated and, after an extreme dip between in 2016 and 2019, returned in 2020 to be slightly higher than in 2015. The general decreasing trend can be explained by domestic issues such as the currency and inflation crisis and the spill-over effects of the Syrian crisis on Turkey’s border security, which likely augmented the government’s defence expenditures, possibly reducing its aid disbursements.

Table 1: SSA and North Africa’s Share of Turkey’s Total Gross ODA Disbursement (in %), 2015-2020

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

SSA

9.66

1.77

1.62

1.26

1.11

0.71

North Africa

0.020

0.002

0.001

0.002

0.0003

0.037

Source: Author’s construct based on OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics, 2022

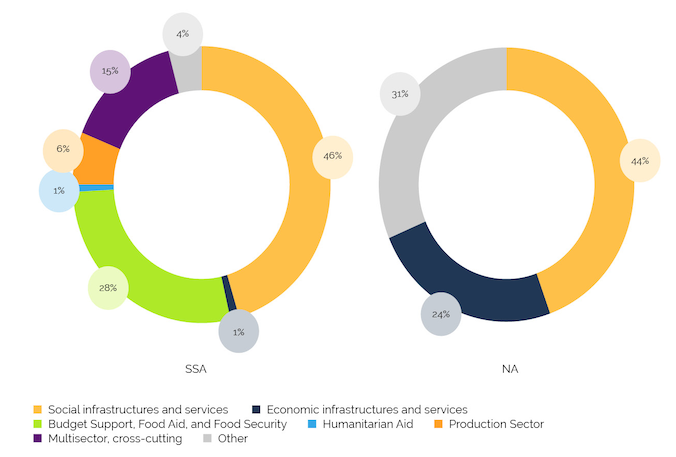

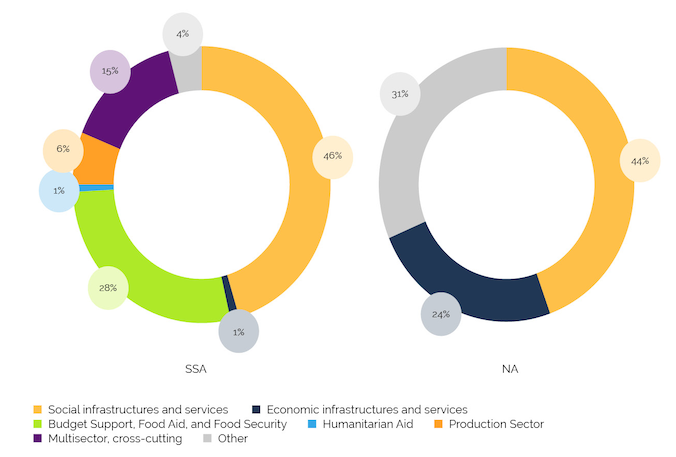

In terms of the sectoral priorities of Turkey’s development policy in Africa, Figure 1 shows that economic infrastructures and services occupied the third place in the case of NA in 2020 against the 5th place in the case of SSA. In this respect, Turkey’s aid policy towards NA shares some minimal common features with the aid policies of emerging donors intervening in Africa, such as China. Those donors have focused extensively on economic infrastructures in their aid distribution. Interestingly, for Turkey’s assistance to SSA, this is not the case as the second-largest policy area receiving aid is budget support, food aid and food security; economic infrastructures and services play only a small role.

Figure 1: Turkey’s Total ODA Gross Disbursements per Sector to SSA and NA as a Percentage of Total ODA in 2020

Source: Author’s construct based on the OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics, 2022

In terms of aid channels, the OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics show that, in 2018, 2019 and 2020, Turkey provided all of its ODA to NA and SSA through bilateral channels. Turkey’s preference for bilateral ODA can be explained by the fact that, as a foreign policy instrument, aid can be easily aligned with Turkey’s foreign policy interests and priorities when channelled directly to the recipient countries rather than passing through multilateral international organisations.

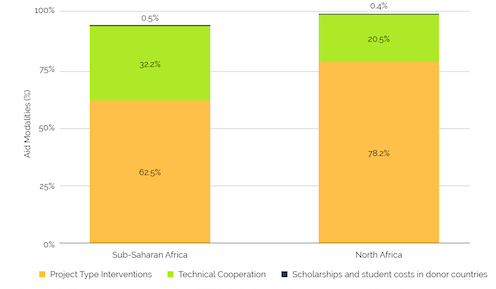

For the types of assistance used in Turkey’s development aid activities in SSA and NA, Figure 2 shows that Turkey only provides grants to these two regions, with no place for loans. This is one of the aspects that differentiates Turkey’s aid from that of both traditional donors such as the EU and emerging donors such as China. By not including loans in its aid types provided to African countries, Turkey could consolidate its identity as a humanitarian actor in Africa and its positive distinctiveness. Likewise, although project-type interventions represent more than half of the Turkish aid in both NA and SSA, the country does not seem to prioritise the use of budget support in Africa since no budget support was provided to either of the two subregions in 2020.[3] Besides project-type interventions, technical cooperation ranks as Turkey’s second most used aid modality in both regions. The share of scholarships in Turkey’s ODA disbursement to both NA and SSA was similar in 2020 (0.54% for NA and 0.37% for SSA). In terms of scholarships, between 1992 and 2022, Turkey provided more than 15,000 African students with post-graduate and doctorate scholarships.

Figure 2: Turkey’s Gross Aid Disbursement to SSA and NA by Aid Types and Modalities as a Percentage of Net Total ODA (%), in 2020

Source: Author’s construct based on OECD data (gross disbursements, USD million), 2022

The OECD data also showcase that, as its delivery channels in 2020, Turkey channelled almost all of its ODA to SSA and NA through the public sector, indicating a government-centric feature of its approach, especially to SSA where it did not use non-governmental channels at all.

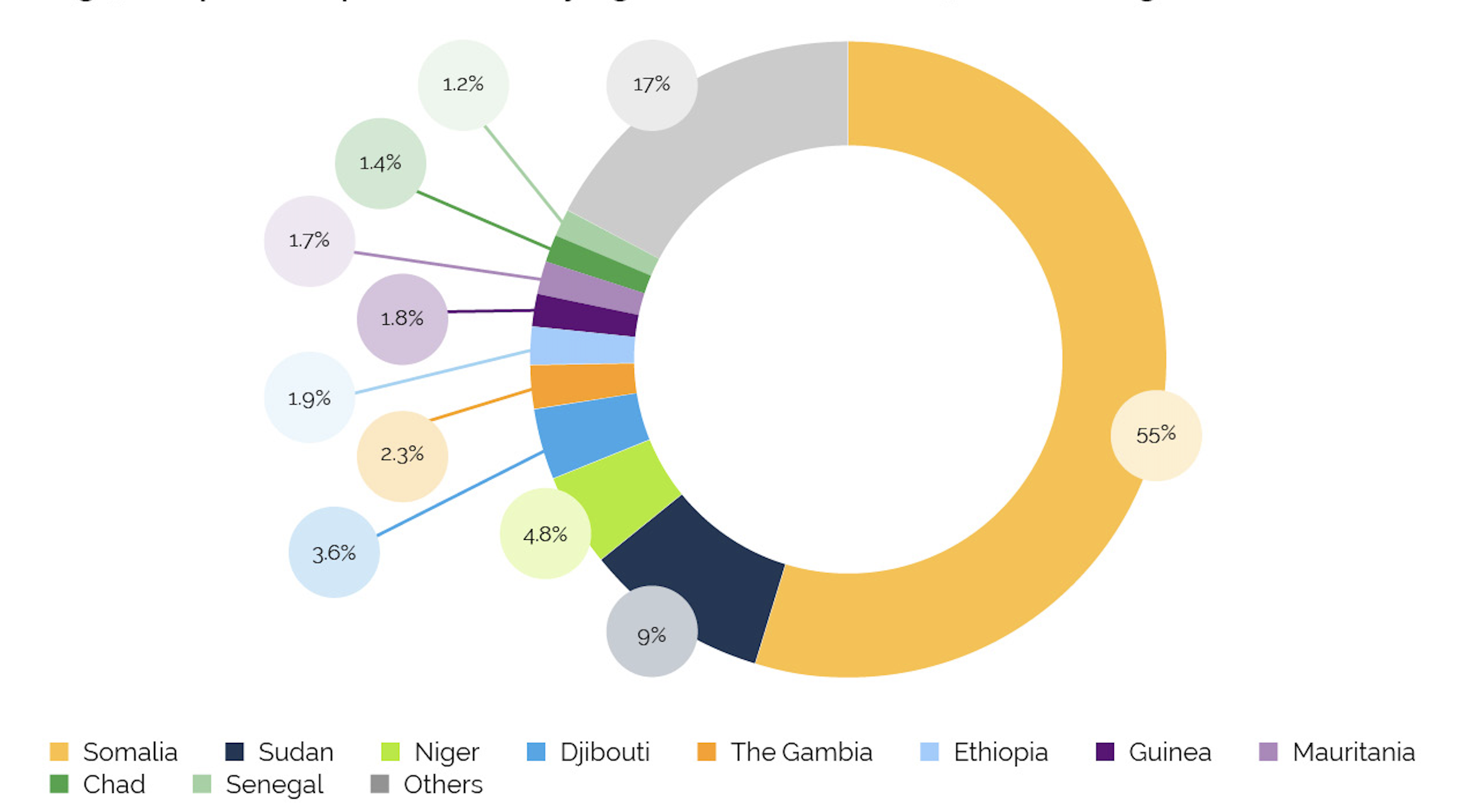

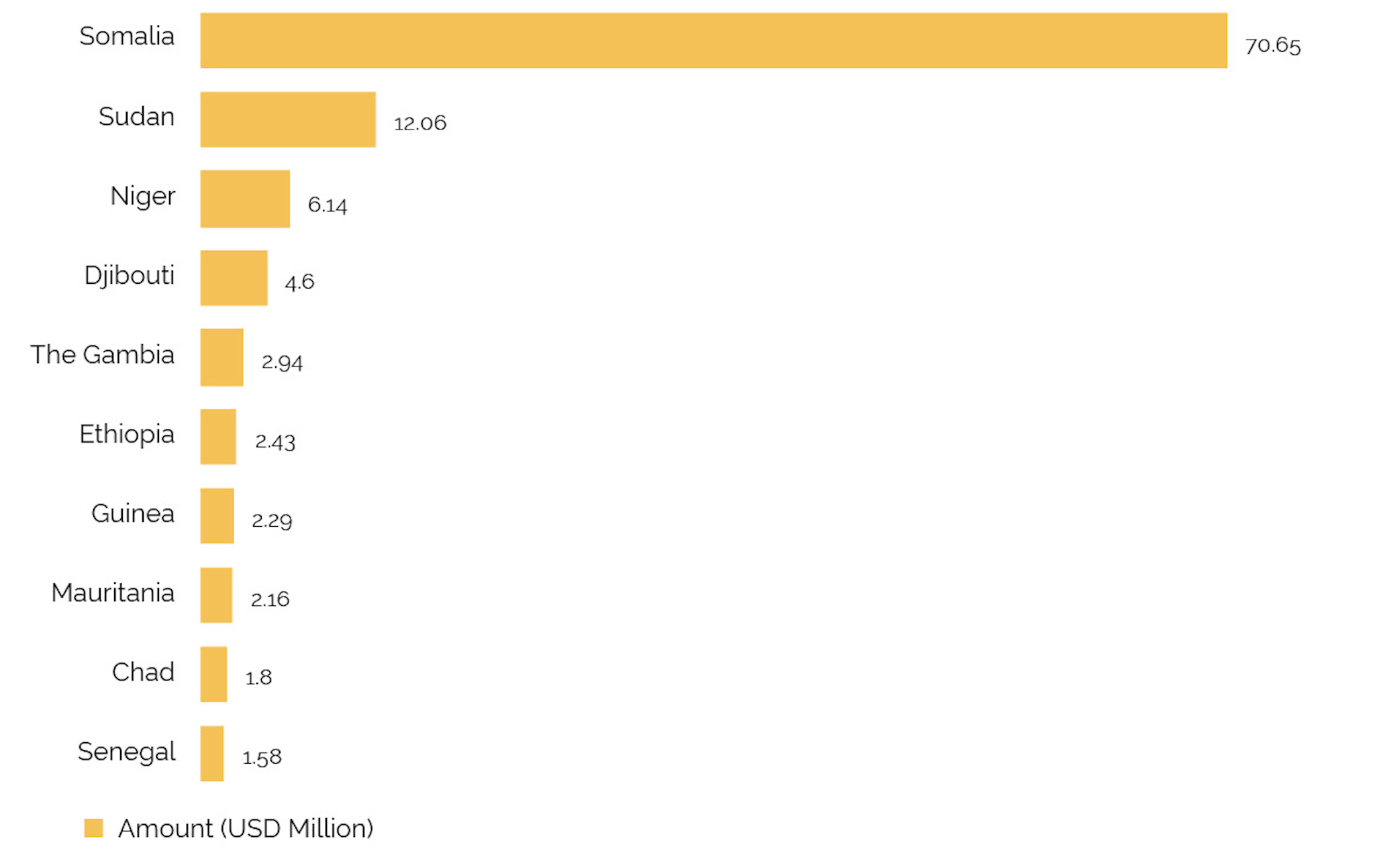

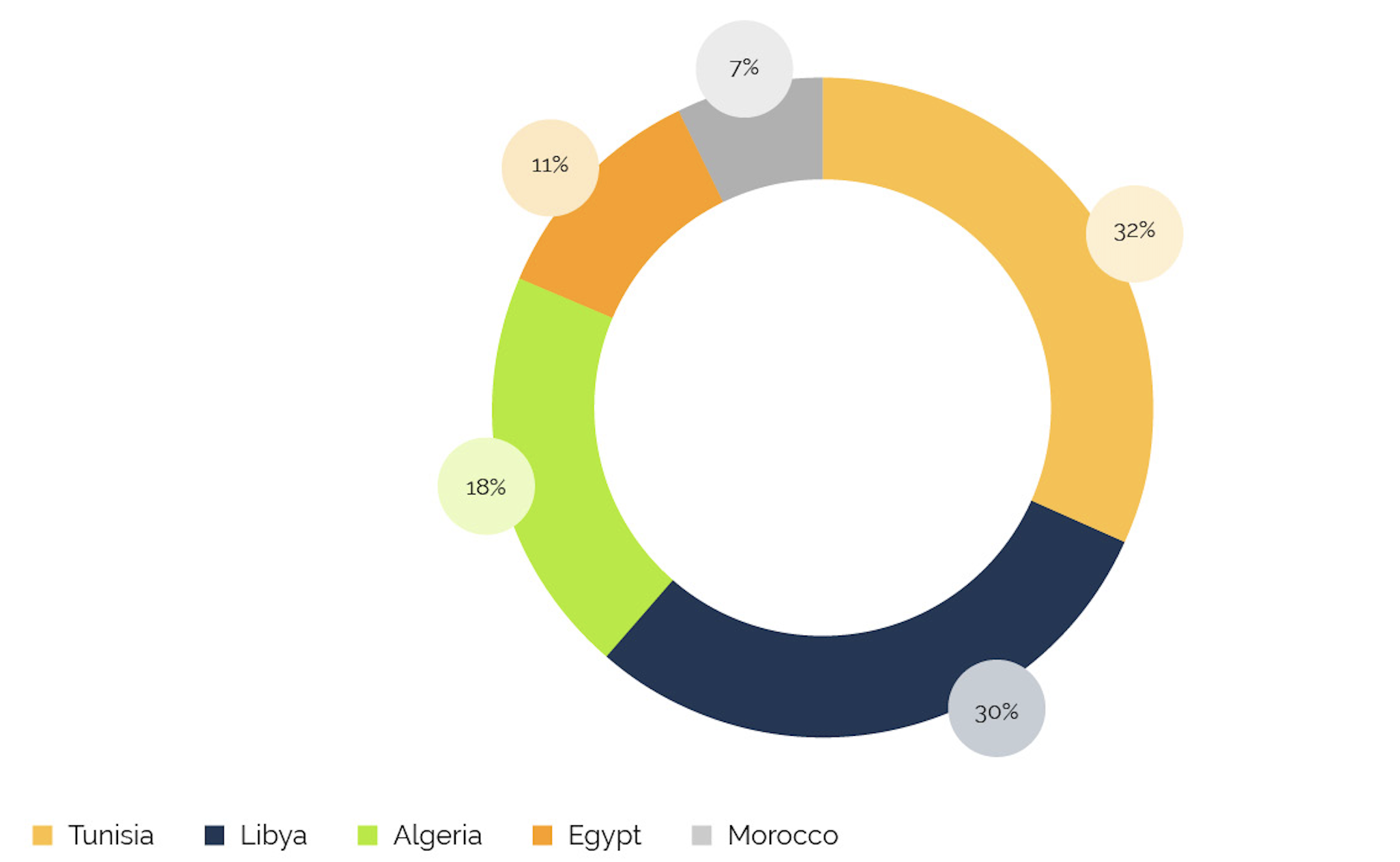

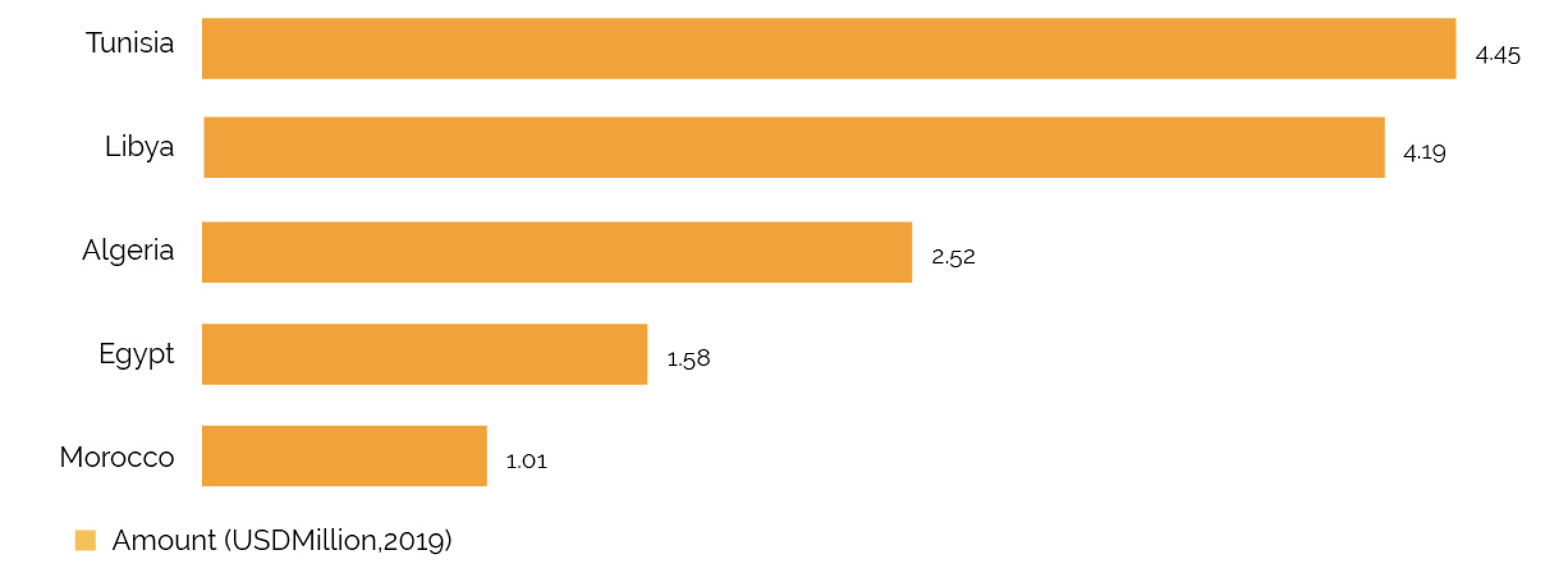

Concerning the geographical distribution of Turkish aid to SSA, Figure 3A indicates that the ten largest SSA aid-recipient countries between 2015 and 2020 were Somalia (54.9%), Sudan (9.37%), Niger (4.77%) Djibouti (3.57%), Gambia (2.28%), Ethiopia (1.88%), Guinea (1.77%), Mauritania (1.67%), Chad (1.42%) and Senegal (1.22%). Of note is that the OECD considers all recipient countries as Least Developed Countries. The related figures for NA are given in Figure 4A, where it can be seen that Tunisia (32.36%), Libya (30.47%), Algeria (18.32%), Egypt (11.49%) and Morocco (7.34%) rank as the top recipients of Turkey’s ODA in the region.

Figure 3A: Top ten recipients of Turkey’s gross ODA in SSA, 2015-2020 Average

Source: Author’s Construct based on OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics, 2022

Figure 3B: Top ten recipients of Turkey’s gross ODA in SSA in 2019 (USD Million)

Source: Author’s construct based on OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics, 2022

We can infer from the statistics on geographical distribution that, for SSA, most Turkish funds went to Muslim-majority countries, some with Ottoman-era connections, like Somalia, Ethiopia and Sudan. There is an essential gap between the top recipient, Somalia (receiving more than half of the total ODA, see Fig. 3B), and the remaining nine recipients. Most of these countries rank among the poorer countries in SSA, illustrating that Turkey’s aid disbursement is mainly based on the needs of the recipient countries. This needs-based character is further exemplarily illustrated by the fact that, in 2019, Tunisia, the top recipient of Turkey’s ODA in NA (see Figure 4B), received less aid than any of the top four recipient countries in SSA (Somalia, Sudan, Niger and Djibouti, see Figure 3B). Turkey’s increasing engagement in the geostrategic countries in the Sahel region and in countries in the horn of Africa also shows that geopolitics plays a considerable role in Turkey’s aid policy towards SSA.

Figure 4A: Top recipients of Turkey’s gross ODA in NA, 2015-2020 Average

Source: Author’s Construct based on OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics, 2022

Figure 4B: Top recipients of Turkey’s gross ODA in NA 2019 (USD Million)

Source: Author’s Construct based on OECD Credit Reporting System Statistics, 2022

2.2. Economic engagements

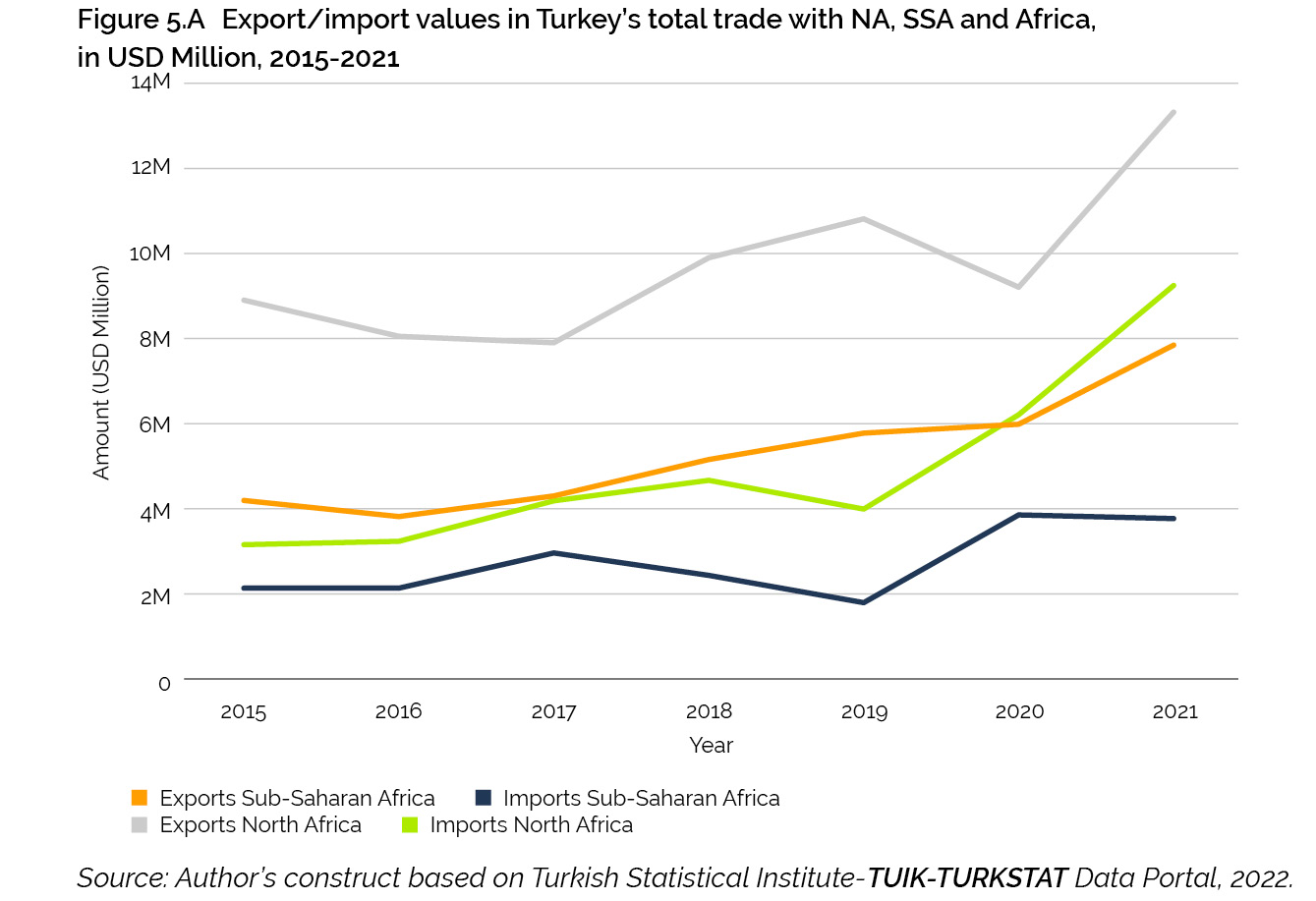

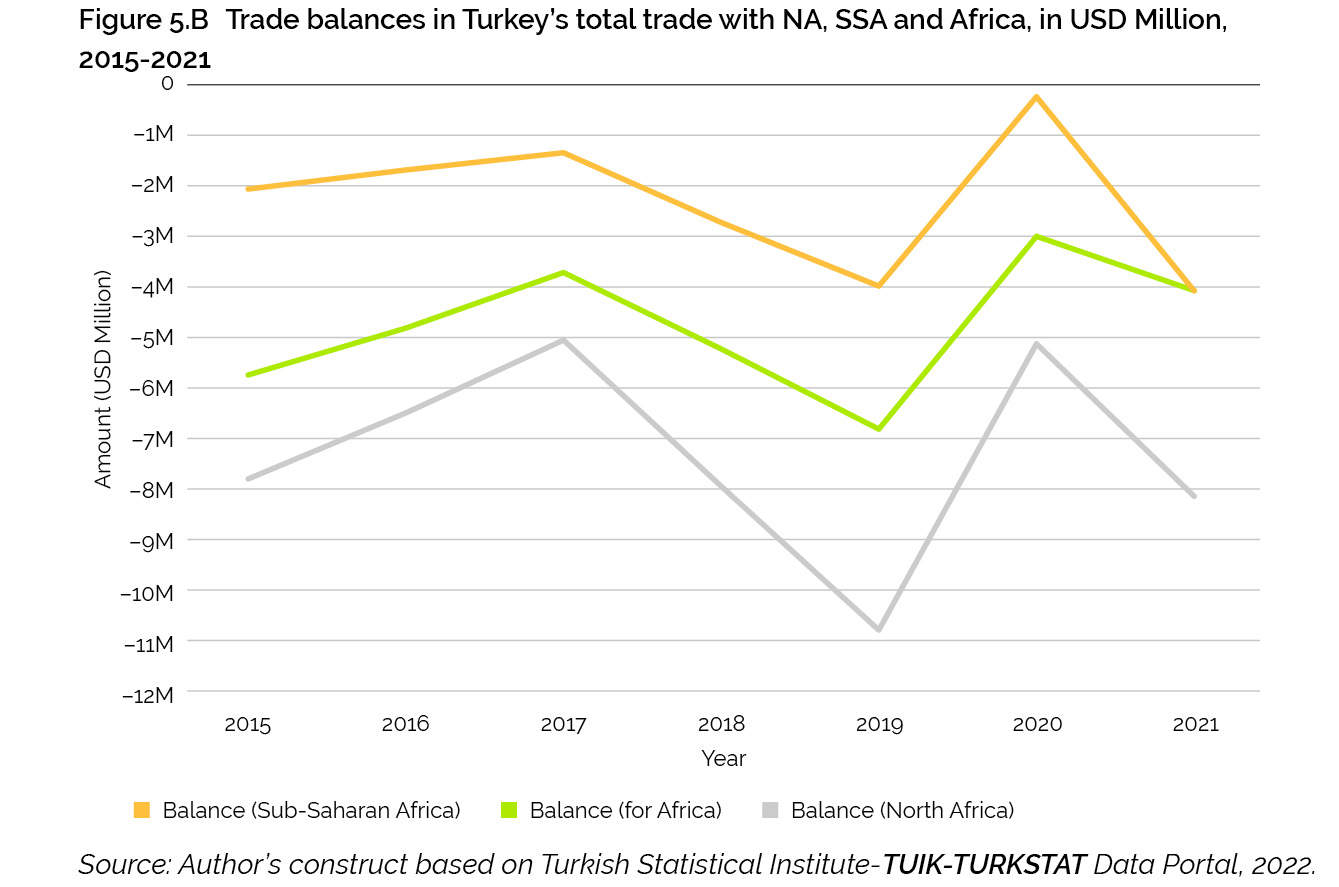

Figures 5A and B show that, from 2015 to 2021, Turkey’s trade volume with NA was far more important than its trade volume with SSA. For instance, in 2020, out of the total trade volume of USD 25billion with the African continent, USD 15billion was with NA. This situation can be explained by the fact that Turkey’s relations with NA are much older than those with SSA and North African countries’ exports are more diversified than those of SSA countries. Figure 5 further shows that Turkey’s trade with Africa generally started to increase from 2016 onwards. For instance, Turkey’s trade with Africa increased from USD 25billion in 2020 to USD34billion in 2021, connoting Turkey’s increasing trading actorship on the continent, although Africa registered a negative trade balance with Turkey across both years.

Figure 5A: Export/import values in Turkey’s total trade with NA, SSA and Africa, in USD, 2015-2021

Source: Author’s construct based on Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK-TURKSTAT Data Portal, 2022.

Figure 5B: Trade balances in Turkey’s total trade with NA, SSA and Africa, in USD, 2015-2021

Source: Author’s construct based on Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK-TURKSTAT Data Portal, 2022.

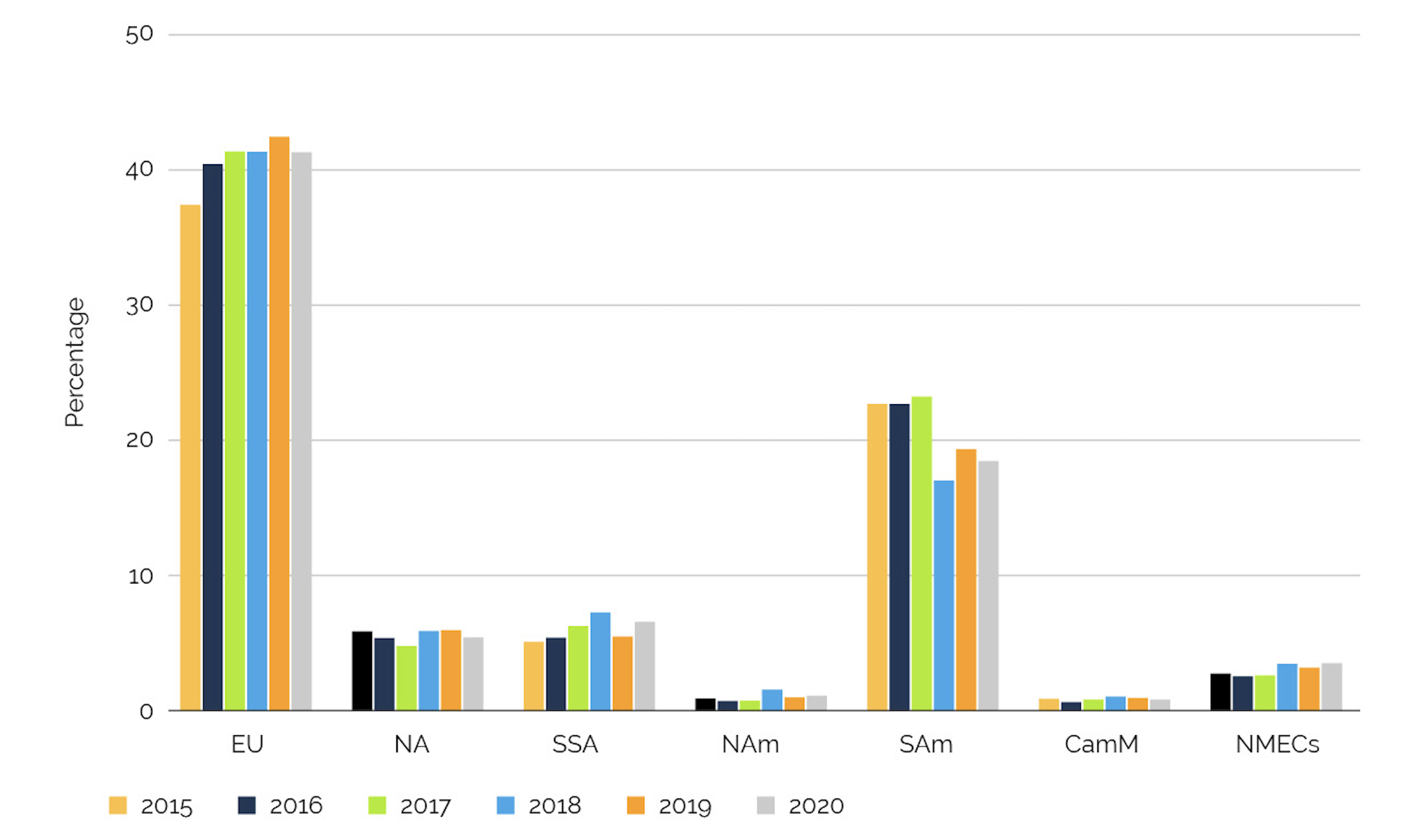

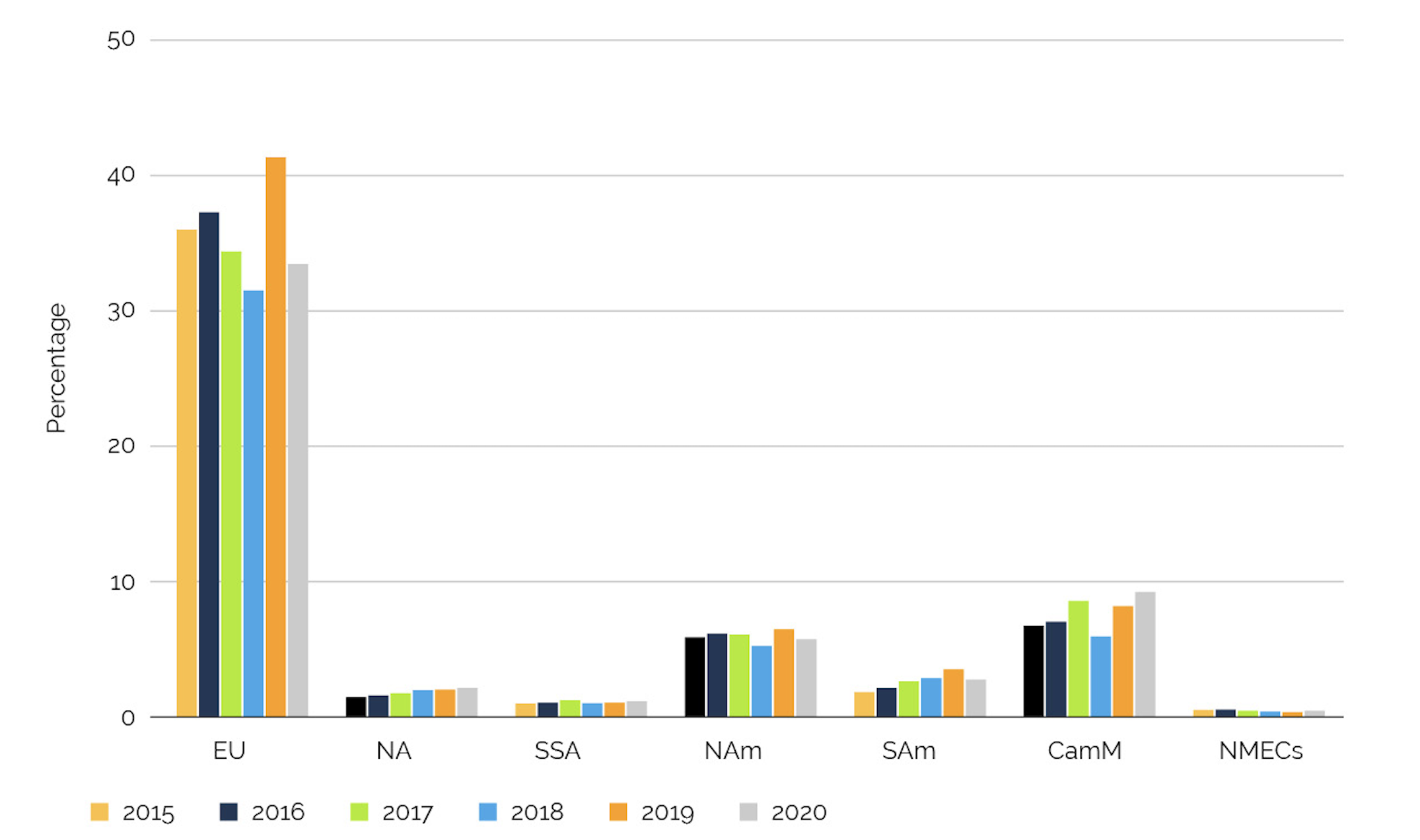

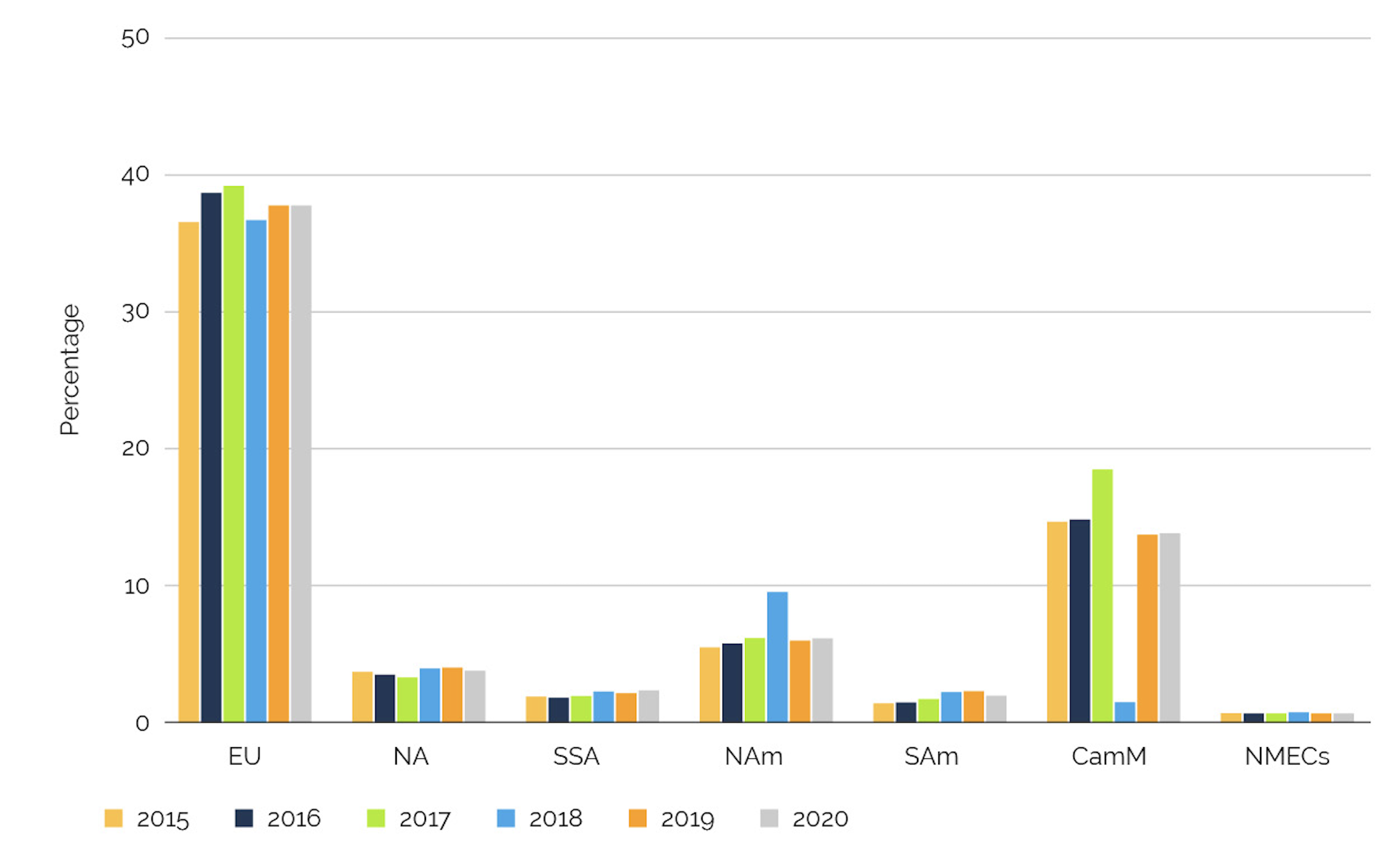

Figures 6 (A, B and C) show that, despite the sharp increase in Turkey-Africa trade volume in the past ten years, Africa’s share of Turkey’s total trade with the world remains small; Africa is not ranked among Turkey’s key trading partners (Turkey’s top trading partners according to Figures 6 include the EU, Near and Middle Eastern countries and North America). For instance, in 2020, whereas Africa’s (SSA+NA) share of Turkey’s total trade equalled only 6.14%, the EU’s and the Near and Middle Eastern countries’ shares, respectively, amount to 41.27% and 18.47%. Furthermore, the asymmetry in Turkey’s trade exchange with both SSA and NA is much more pronounced compared to that of the other regions because the African regions’ share of Turkey’s total world exports is threefold more than their share of Turkey’s total world imports (Figures 6A and 6B).

This low ranking of the African continent among Turkey’s trading partners can be partly explained by the low number of Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) concluded with African countries (so far four FTAs concluded with Morocco in 2004, Tunisia in 2004, Egypt in 2005 and Mauritius in 2011) and the double taxation faced by business people from both sides.

Figure 6A: 2015-2020 share in Turkey’s exports by regions (in %)

Source: Author’s construct based on Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK- TURKSTAT Data Portal, 2022

Figure 6B: 2015-2020 share in Turkey’s imports by regions (in %)

Source: Author’s construct based on Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK- TURKSTAT Data Portal, 2022

Figure 6C: 2015-2020 share in Turkey’s total trade by regions (in %)

Source: Author’s construct based on Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK- TURKSTAT Data Portal, 2022

Note: for all 3 figures: EU: European Union, NA: North Africa, SSA: Sub-saharan Africa, NAm: North America, SAm: South America, NMECs: Near and Middle Eastern Countries, CamC: Central America and Caribbean

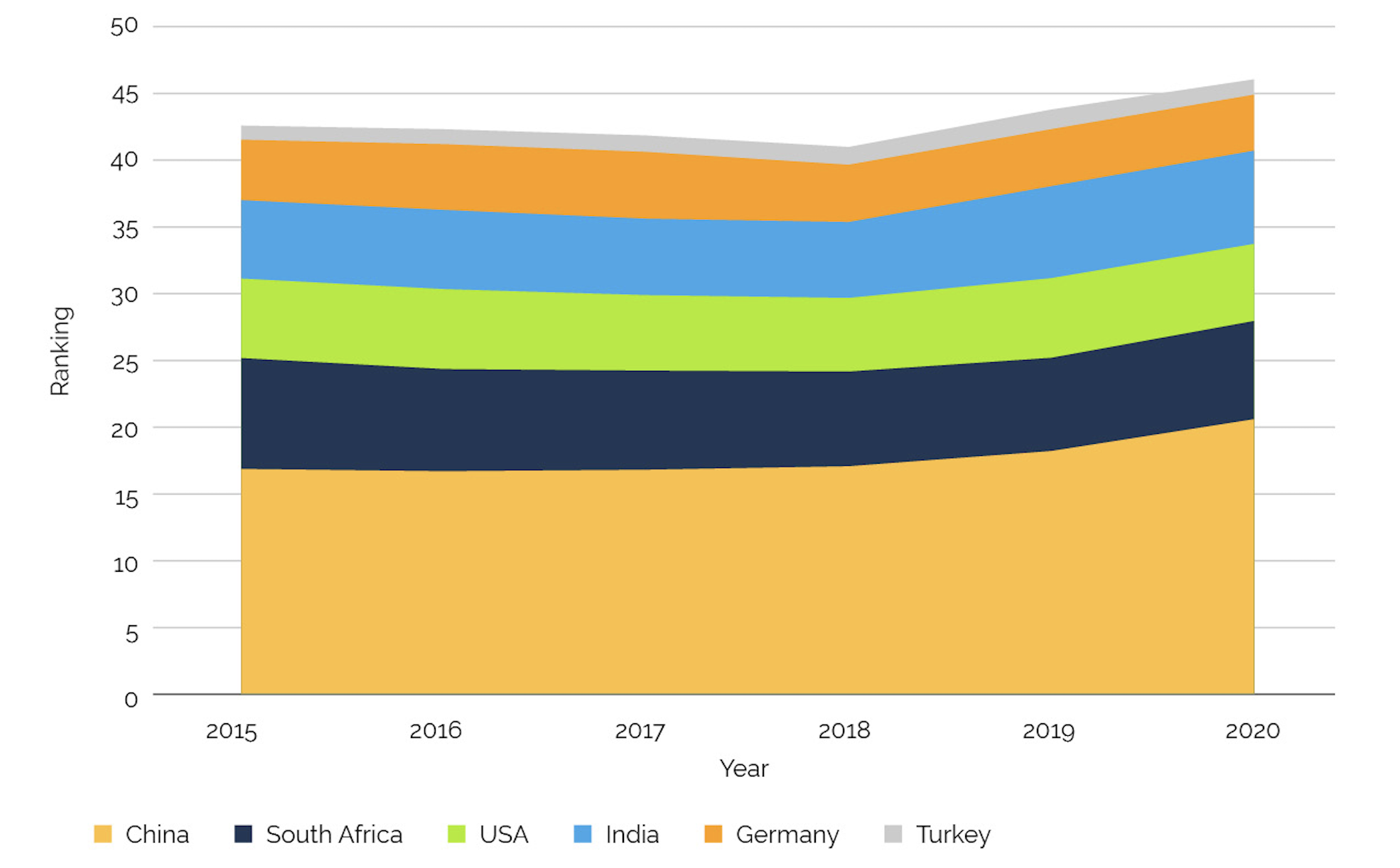

Figure 7 illustrates Turkey’s position in the SSA trade landscape and shows that, although Turkey does not rank among the highest top trading partners of SSA, it has managed to secure a non-negligible position, which is remarkable given the short time of its engagement. For instance, in 2018 and 2019, Turkey secured the place of Africa’s 19th largest exporter with a share of, respectively, 1.33% and 1.47%. But this position falls sharply when it comes to its position among SSA’s largest importers, although it improved its position from 38th place in 2018 (0.49%) to 30th place in 2019 (0.74%).

Figure 7: SSA’s top five export partners’ shares compared to Turkey’s share, 2015-2020 (in %)

Source: Author’s construct based on World Bank-World Integrated Trade Solution (WITS), 2019 Country Profile, 2022

For Turkey’s top trading partners in Africa between 2015 and 2021, Table 2 showcases that, out of the top ten trading partners, five are from NA and the other five from SSA are located mainly in the West, East and Southern parts of the region. The five NA countries comprised about 60.98% and 71.96% of Turkey’s total trade volume with Africa, respectively in 2020 and 2021. This first ranking of North African countries could be easily explained by their long-standing relations with Turkey since the Ottoman era, their geographical proximity and the more developed infrastructures and industrialization levels.

Table 2: Top ten trading partners of Turkey in Africa, 2015-2021

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Trade Balance- 2020(USD Mio)

Trade Balance-2021(USD Mio)

Egypt

25.43%

27.9%

23.49%

24.2%

17.70%

19.31%

29.92%

1 381 731 341

832 027 637

Algeria

13.01%

15.17%

13.51%

14.75

12.18%

12.20%

12.17%

-192 374 964

-772 878 671

Morocco

12.41%

13.98%

13.47%

12.54%

13.63%

10.65%

11.38%

1 415 060 105

2 054 451 804

Libya

9.27%

6.99%

5.91%

8.79%

11.37%

14.53%

13.38%

-374 227 997

958 579 285

Tunisia

5.79%

6.74%

6.02%

5.36%

4.79%

4.29%

5.11%

767 485 178

1 000 985 890

South Africa

8.53%

12.36%

11.37%

8.71%

5.89%

5.77%

5.99%

-313 866 525

-331 479 118

Nigeria

2.82%

2.27%

2.5%

2.30%

3.35%

7.76%

5.57%

-743 995 491

-229 405 698

Sudan

*

3.24%

2.56%

2.07%

*

1.89%

*

269 996 861

173 821 598

Ethiopia

2.34%

2.6%

1.98%

1.65%

1.92%

*

*

190 846 600

329 929 973

Ivory Coast

2.16%

2.18%

2.13%

1.68%

1.83%

2.48%

2.41%

-14 733 111

35 229 310

Ghana

2.26%

*

*

2.12%

2.12%

3.04%

1.96%

183 445 695

342 552 129

Mauritania

*

*

*

*

*

*

2.00%

>92 692 037

132 667 942

Note: * country not ranked among Turkey’s top ten trading partners for that year

Source: Author’s construct based on Turkish Statistical Institute-TUIK- TURKSTAT Data Portal, 2022

One other point of interest is shown in Table 2. Among the top ten trading partners of Turkey in Africa, only South Africa, Nigeria and Algeria maintained a positive trade gap with Turkey successively in 2020 and 2021. The balance with these countries breaks with the overall existing imbalance in Turkey’s trade exchange with African countries.

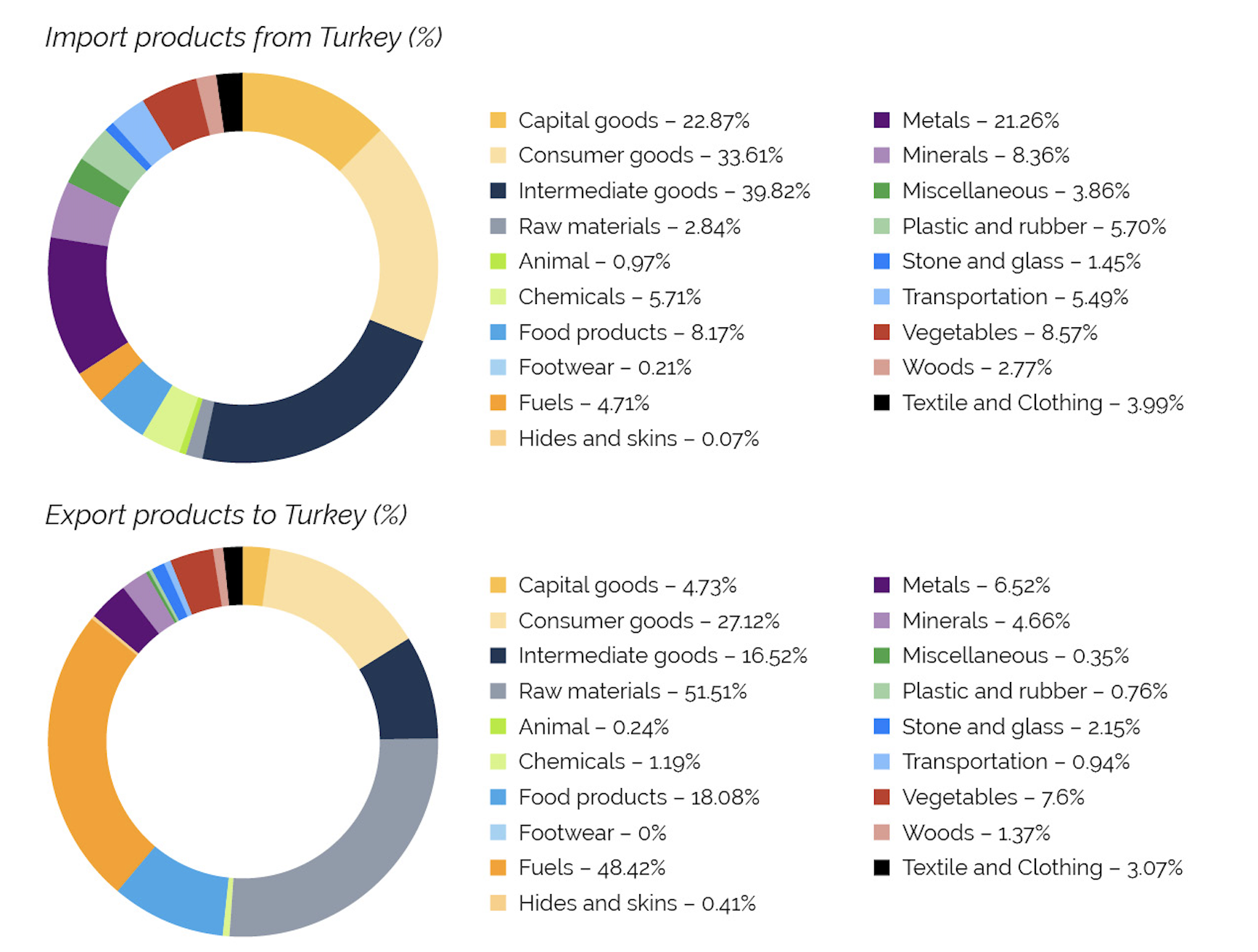

In terms of product shares, Figure 8 shows that raw materials made up the largest group (around 51.51%) of SSA’s export products to Turkey between 2015 and 2020, followed by fuels (48.42%) and consumer goods (27.12%). The figure indicates further that, in terms of SSA’s imports from Turkey, intermediate goods (39.42%) followed by consumer goods (33.61%) and capital goods (22.89%) constitute the largest product groups imported from Turkey between 2015 and 2020.

Figure 8: SSA’s export and import product share to/from Turkey, average 2015-2020

Source: Authors’ construct based on World Bank-WITS database, 2022.

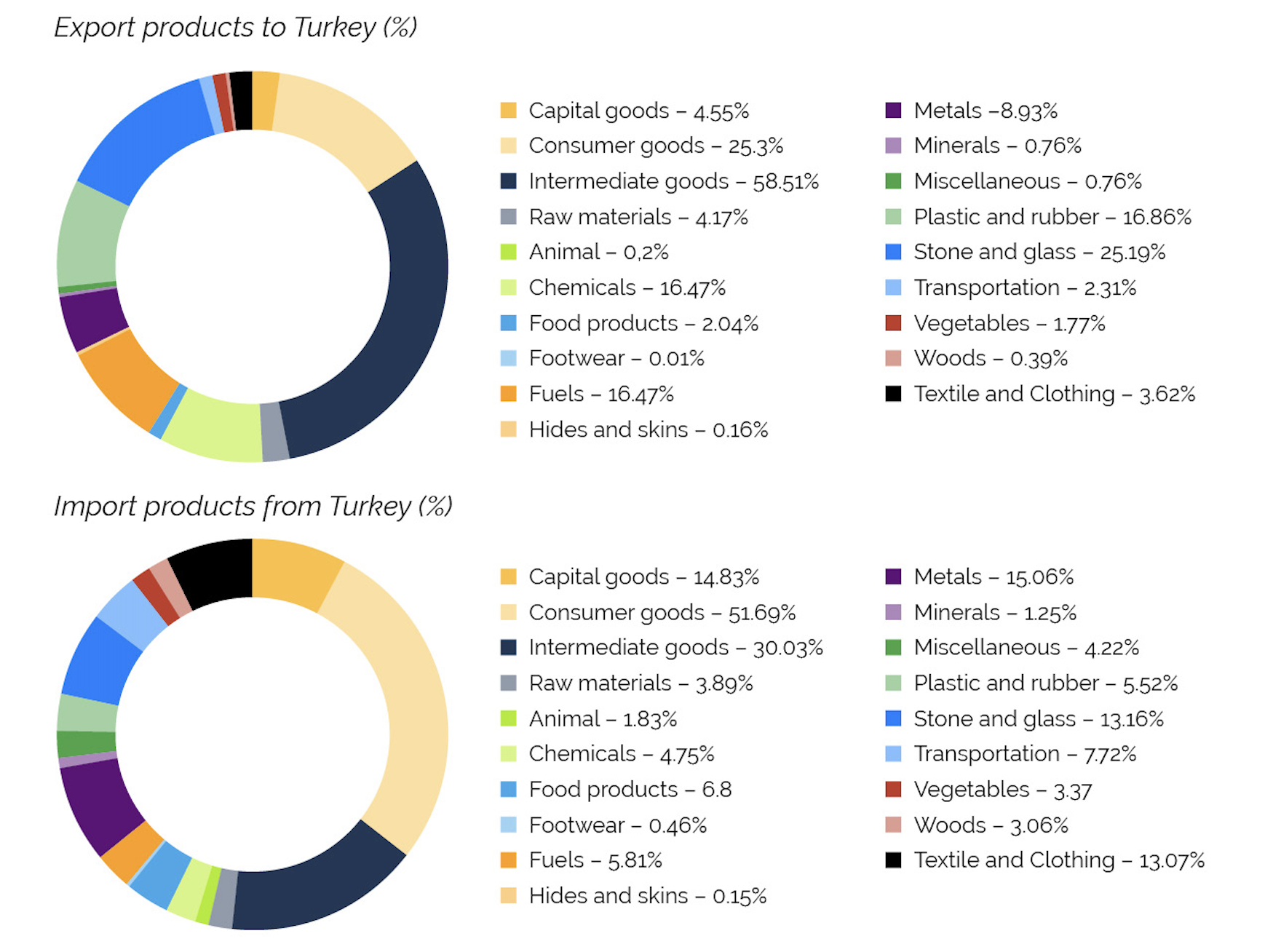

For NA (included in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) figures), the picture is similar to some extent since, according to Figure 9, consumer goods (51.69%) and intermediate goods (30.03%) made up the largest import product groups of MENA from Turkey between 2015 and 2020. However, the picture for MENA exports to Turkey is almost reversed: Intermediate goods (58.51%) are the largest export group to Turkey, with consumer goods coming second (25.3%). Of note in figures 8 and 9 is that SSA had a large positive trade balance in raw material exchange with Turkey whereas NA had a small negative trade balance i.e., SSA is exporting a much larger volume of raw materials to Turkey than it is importing, whereas NA is importing slightly more raw materials than it is exporting.

Figure 9: MENA’s imports and export product share with Turkey, average 2015-2020

Source: Author’s construct based on World Bank- WITS database, 2022.

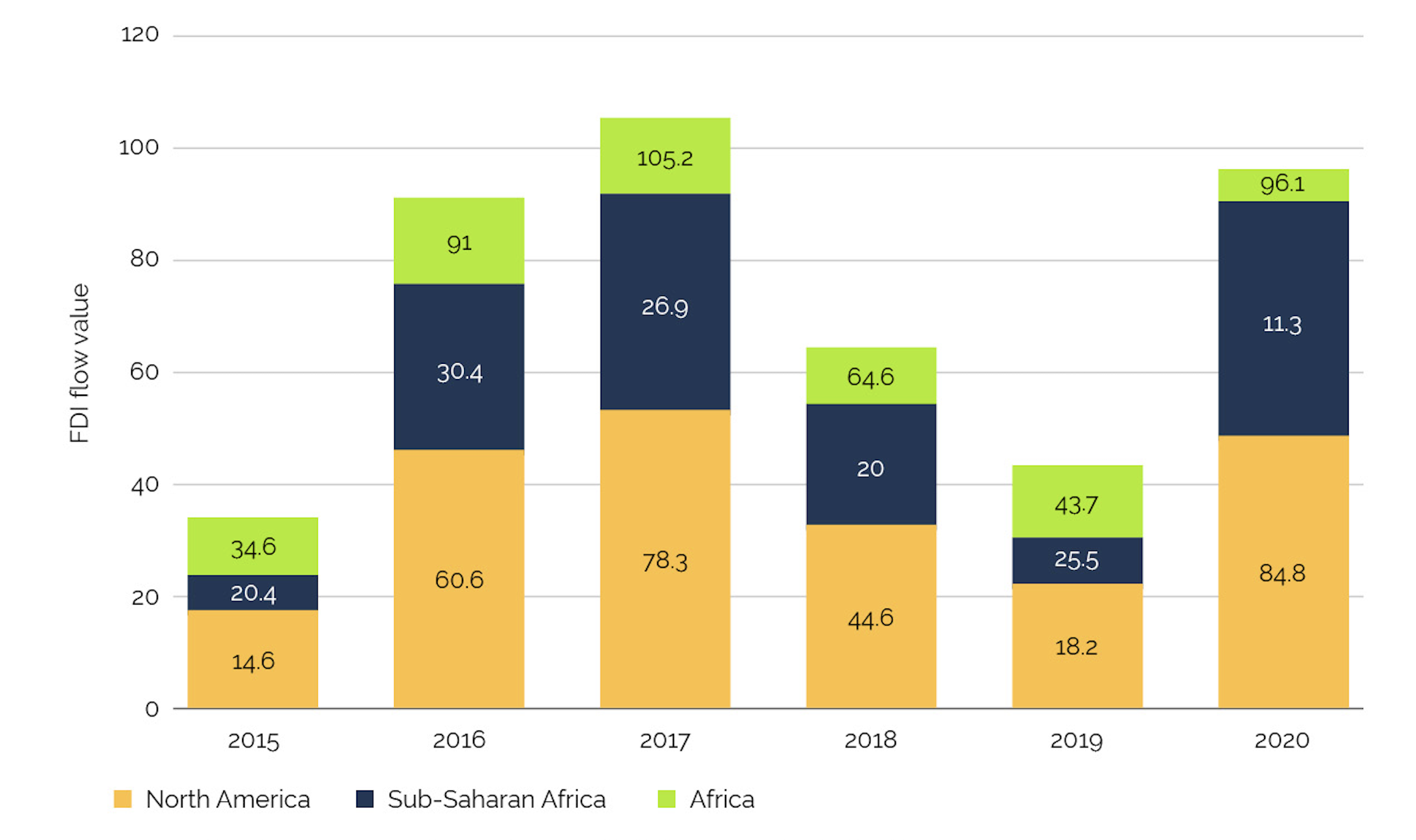

In terms of foreign direct investment (FDI), Figure 10 showcases that Turkey’s FDI outflow value to Africa in 2020 was USD 96.1million, of which USD 84.8million went to NA and only USD 11.3million to SSA. In general, according to OECD statistics, Turkey’s FDI outflow to Africa increased from USD 34.6million in 2015 to USD 96.1million in 2020. On average, between 2019 and 2020, the top recipients of Turkey’s outward FDI flows in Africa were Tunisia, Algeria, Egypt, Sudan, South Africa, Morocco, Kenya, Ivory Coast, Nigeria and Zambia (Table 3). Table 3 shows that most of Turkey’s FDI still concentrates on NA and a few large economies in SSA.

Turkey’s investment in SSA is particularly visible in the infrastructure sector, where Turkey is also enhancing its role and Turkish companies are gaining increasingly big infrastructural building projects. One of the largest Turkish companies, Summa, won several important contracts in the building sector in Africa, including the rebuild and running of Guinea Bissau’s new international airport in March 2022, the construction of the Senegalese national stadium completed in February 2022 as well as the construction of airports in Niger, Senegal and Sierra Leone. In 2021, the value of projects undertaken by Turkish builders in SSA was USD 5bn, or 17% of all Turkish building projects abroad, up from a paltry 0.3% before 2008. The region has overtaken Europe (10%) and the Middle East (13%) and, in Turkish building projects, is second only to countries of the former Soviet Union.

Figure 10: Turkey’s outward FDI flow value to Africa, in Mio USD, 2015-2020

Source: Author’s construct based on OECD Outward FDI Statistics by partner country, 2022

Table 3: Main ten destination countries of Turkey’s outward FDI flows to Africa, 2015-2020 and 2019-2020 Average Value in Mio USD

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

Outward FDI Flows (2019-2020 average)

Egypt

7.4%

24.9%

30.8%

3.8%

7.4%

7.7%

7.55%

Algeria

3.5%

26.0%

39.2%

11.1%

9.3%

6.6%

7.95%

Morocco

1.0%

9.4%

7.4%

28.2%

1.0%

5.3%

3.15%

Mozambique

1.7%

2.3%

6%

*

*

*

*

Tunisia

2.2%

*

1.0%

*

*

65.3%

32.75%

South Africa

8.8%

*

*

7.0%

5.6%

2.3%

3.95%

Nigeria

*

11%

1.8%

*

*

2.4%

1.2%

Sudan

*

*

*

*

10%

*

5%

Ethiopia

*

1.6%

1.7%

2.8%

0.7%

*

*

Ivory Coast

2.0%

7.7%

12.1%

0.9%

4%

*

2%

Kenya

2.1%

1.8%

*

4.0%

3.4%

0.6%

2%

Ghana

*

*

*

1.9%

*

*

*

Mauritania

3.4%

1.9%

2.2%

*

*

*

*

Angola

0.7%

*

*

*

*

*

*

Zambia

*

*

*

*

1.4%

1.0%

1.2%

Senegal

*

1.6%

2.0%

1.4%

*

*

*

Cameroun

*

*

*

*

0.4%

*

*

Guinea Bissau

*

*

*

1.1%

*

*

*

Mauritius

*

*

*

*

*

0.8%

*

Uganda

*

*

*

*

*

2.6%

*

Note: * country not ranked among the top ten destination Countries of Turkey’s outward FDI flows to Africa in that particular year

Source: Author’s construct based on OECD Outward FDI Statistics, 2022

2.3 Defence Sector-related Engagements

Turkey’s Africa policy has been marked by a mix of both soft and hard elements, in particular since 2016, which marked an important turning point in Turkey’s foreign policy. Turkey has become much more engaged in developing its defence industry, especially since the 2016 failed military coup and the implementation of an arms embargo against Turkey by some of its Western allies as a reaction to Turkey’s military operations in northern Syria. Those events pushed Turkey to step up the development of its defence industry with the aim of reducing its military dependence vis-à-vis Western powers. The most prominent of these developments are the Bayraktar TB-2 combat and surveillance drones, which have become more widely popular since their use in the Syrian, Libyan, Nagorno-Karabakh and Ukraine crises. These drones are considered to be as efficient as Western-made drones while being cost-efficient without political strings attached and affordable to countries in the developing world. President Erdoğan expressly mentioned the popularity of drones in Africa during his visit to Angola, Nigeria and Togo in October 2021 in the following words: ‘‘Everywhere I go in Africa, everyone asks about UAVs’’ (unmanned aerial vehicles).

In this context, the African continent has been the stage of terrorist attacks from the Horn to the Sahel regions. Apart from attacks from Al-Shabab in the Horn of Africa, the Sahel region in West Africa is currently facing major terrorist threats with the increasing implementation of al-Qaeda branches in this region since the fall of the Kaddafi regime in 2011. Grabbing the opportunity that most of the states in the Sahel face political instability with low governmental capacities, the terrorist groups have gained power and enlarged their local branches through their greater capacity for local recruitment. In this context of increased insecurity, despite the plethorically military presence of external partners committed to helping the Sahel countries in the fight against terrorism, including the Barkhane Force (initially established in Mali but relocated recently to Niger with come components in Burkina Faso amidst mounting tensions between Paris and Bamako), the multinational European Task Force, Takuba forces, combined with the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission In Mali (MINUSMA). In this vein, some authorities and citizens in the Sahel region have increasingly emphasised the necessity to diversify their defence partners, and citizens are strengthening their call for the departure of French troops from the Sahel.

The successive coup d’état observed in Mali and Burkina Faso are the culmination of this rise of anti-French sentiment amidst rising suspicion about the frank engagement of France in this combat and the popular sentiment that defence partners should be diversified to win the fight against terrorists in the Sahel. In this context of contestation and challenge to the legitimacy of the traditional security partners in African countries, Turkey, benefiting from its non-colonial past in the continent, has started to increase its security activism. This activism ranges from its involvement in the state-building process of Somalia to its military presence in the continent with the establishment of its first military base in Somalia in 2017 (TURKSOM) and more recently to the intensification of its arms sales to Africa and its drone diplomacy. As of 2022, Algeria, Libya, Chad, Niger, Ghana, Mauritania, Senegal, Rwanda, Uganda, Kenya, Gambia, Somalia and Ethiopia have reportedly purchased wheeled-type armoured personnel carriers.

In terms of unmanned combat aerial vehicles (UCAVs) and drones, since September 2022, Morocco, Libya, Ethiopia, Somalia, Niger, Togo and Burkina Faso have purchased them from Turkey (Table 4). The most recent drones’ delivery to African countries includes ones to Niger, Togo and Burkina Faso. Niger, which at the beginning of 2022 expressed its interest in purchasing the drones, has finally purchased them and reportedly received the first delivery of the Turkish drones a few months ago as part of an arms contract signed in November 2021. Recent weeks have seen a consignment of Bayraktar TB2s delivered to the West African states of Togo and Burkina Faso.

Table 4: Turkey’s military hardware sales to Africa 1998- 2022

Hardware Sold

Buyers

Wheeled Type Armoured Personnel Carrier

Algeria

Mauritania

Senegal

Ghana

Burkina Faso

Nigeria

Niger

Chad

Libya

Tunisia

Ethiopia

Somalia

Kenya

Uganda

Rwanda

Unmanned Combat Aerial Vehicles (UCAVs)

Libya

Tunisia

Morocco

Ethiopia

Somalia

Niger

Togo

Burkina Faso

Source: Author’s construct based on data from CATS, UNROCA & DW, 2022

Figure 11 shows the top recipients of Turkey’s arms sales to Africa. It indicates that most of these recipients are located in West, East and North Africa. According to the data, Tunisia ranks first as the largest importer of Turkey’s arms in Africa with a share of 26.2% followed by Nigeria (18.3%), Libya (11.0%), Egypt (7.3%), Rwanda (7.3%), Burkina Faso (5.5%), Ghana (4.9%), Morocco (4.9%), Uganda (3.7%) and Senegal (3.0%). Whereas Turkey’s arms exports market in Africa included only two countries in 2017 (Tunisia and Rwanda),[4] from 2017 to 2021, it multiplied its partners to 12 countries (Figure 11).

Figure 11: Top ten recipients of Turkish arms exports in Africa, 2006-2021, in %

Source: Author construct from SIPRI’s Trend Indicator Value, SIPRI arms transfers database, 2022

According to one Turkish foreign policy official interviewed, since establishing government-to-government relations constitutes the backbone of Turkey’s African strategy, Turkey does not sell arms to rebel groups, private militias or guerrilla forces. It is likely that, due to their success in Ukraine, the cost-effective drones Bayraktar TB2 from Turkey will continue to gain the attention of most African countries in the short- and mid-term. At the same time, however, the increase in the value of arms sales to Africa, although contributing to advancing Turkey’s actorship on the international stage and to its economy, might tarnish Turkey’s image in Africa in the longer term. Indeed, many African countries are faced not only with terrorism but also with ethnic-based conflicts, as is the case in Ethiopia. Given the marketing and media coverage surrounding Turkey’s drone sales in Africa, Turkey may risk losing its credibility in the eyes of some Africans as a neutral actor in African politics. For example, it is not rare to see comments from Ethiopians siding with the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF) accusing Turkey of providing ‘indirect’ support to the Ethiopian government in the war against the Tigrayan by delivering drones to Ethiopia.

Here it is important to remember that Turkey’s arms sales to Africa are far less than those of the largest exporters of arms to Africa: Russia, USA, China and France.[5] Turkey currently shares only 0.5% of Africa’s total arms imports from outside the continent. As a newcomer to the African arms market, what makes Turkey attractive in this picture is its rapid entry into the market, partly pushed by the 2008 financial crisis that hit its traditional western trade partners and its low-priced and therefore competitive drones.

Besides the increase in the value of bilateral arms sales, Turkey also contributes to established African regional security organisations such as the G-5 Sahel[6] to combat terrorism. For instance, in March 2018, Turkey granted the G5 Sahel Joint Force USD5million. Turkey contributed (or is still contributing) with personnel to UN Peacekeeping missions in Africa, including the United Nations Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS), the United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in DR Congo (MONUSCO), United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA), the United Nations – African Union Hybrid Operation In Darfur (UNAMID) and the United Nations Integrated Transition Assistance Mission In Sudan (UNITAMS). One can also read from the joint declaration issued at the third Turkey-Africa partnership summit that ‘peace-security and governance’ are selected as one of the five strategic cooperation areas on which Turkey and African countries will work through a joint action plan from 2022 to 2026. Turkey has also sent military attachés to its diplomatic representations abroad in 19 countries in Africa.

As of 2022, Turkey has also signed security and defence-related agreements with 30 states in Africa, among which were military cooperation agreements signed with Niger in 2020, with Togo in August 2021 and with Senegal in February 2022. Turkey also signed a defence pact with Nigeria in 2020 and a defence cooperation agreement with DR Congo in February 2022. It also reportedly signed a military cooperation with Ethiopia in August 2021 amidst the Ethiopian government’s struggle against the Tigrayan rebels. Earlier in 2019, Ankara signed two defence deals including maritime and security aspects and military training with the UN-recognised government in Libya.

3. Africa’s perception of the terms and scale of Turkey’s engagements

African perceptions of the terms and scale of Turkey’s current African policy can be assessed with a special eye on five focus groups: African officials, business circles, African students in Turkey, African think-tanks and Civil Society Organisations (CSOs). Whether these groups see Turkey-African relationships as mutually beneficial and whether they have a mutually inclusive agenda for further deepening of ties in multiple issue areas or not remain central topics in assessing the quintessence of the Turkey-Africa cooperation.

Among the multiple roles of Turkey in Africa, strategic and trading partner appears as the most preferred conceptions attributed to Turkey by our interviewees from the five focus groups. Our interviewees from the embassies of nine Sub-Saharan and three North-African countries in Turkey have both converging and diverging perceptions about Turkey’s position on the continent. Almost all of them see Turkey as a rising donor and trading partner who cares about African needs by pursuing a balanced strategy between its interests and African needs. Here it is important to remember that North African perceptions about Turkey differ slightly from Sub-Saharan ones since Turkey has deeper historical ties inherited from the Ottoman Empire era with all North African countries.

In the NA context, it has also been widely accepted by Turkish policymakers and scholars that Turkey’s Ottoman past raises doubts about its African footprint, and Ankara’s willingness to expand its influence in the region may be linked to the existence of a neo-Ottoman ideology behind Turkey’s proactive African policy and the “great power” self-perception of the current Turkish decision-makers. It is also striking that, despite this scepticism towards Turkey’s African engagements, Turkey-North African ties have improved considerably during the last decade in almost every policy area, including diplomacy, trade and culture/education.

SSA perceptions differ from those of NA in some key aspects. First, only a few SSA countries have lived under Ottoman rule, and they generally attribute positive connotations to the Ottoman era in their history. In their mindset, Turkey’s presence in the continent does not reveal any desire for colonial mimicry, suggesting a completely different understanding of the objectives of Turkey’s African policy. Turkey’s criticism of the major international institutions’ unjust decision-making mechanisms and of the non-representation of the African continent in the UNSC has also been commonly shared by most of the SSA countries. This common sense about the existing unfairness and in equality in the global distribution of power make these countries and Turkey closer, especially in the UN system related to global challenges. Despite Turkey’s strong ties with the Western world, as reflected in its NATO membership and its long-lasting EU candidacy, the SSA countries do not perceive Turkey’s Western ties as counterproductive to their rapidly evolving relations with Turkey.

In contrast, Turkey’s in-between position, between the West and the East, are positively perceived in the eyes of most of the African state officials, businessmen and African students in Turkey. In addition, Turkey’s development and humanitarian aid are conceived by most of the SSA country’s officials and CSOs as rapid and well organised and reaching the needy. This last point also gives Turkey leverage in the international development landscape of Africa in the sense that Turkish aid is mostly bilateral and its disbursement has been made by the Turkish Development Agency (TIKA) to the Turkish embassies and consulates in the target African countries. The bilateral character of Turkish aid is likely to give some advantages to the Turkish authorities in terms of rapidness, transparency and efficiency.

The business relations between Turkey and Africa include an element of the relations between Turkey and African students. In terms of African business people’s perception, African business circles describe the Turkish market as cheap and high quality. According to the Africans we interviewed, among Africans doing business in Turkey, the Senegalese seem to constitute the biggest group, followed by Nigerians. In the Turkish context, the growing influence of African students in Turkey on Turkey-Africa relations matters because they constitute an important part of the current African diaspora in Turkey. Furthermore, a significant number of African students living in Turkey work in the trade sector because Turkish textile products are famous and highly praised in African countries. They are either employed at various textile stores or open their own textile stores in Turkey. In recent years, there has been a growing trend among African students starting a small business by founding courier companies in the major cities of Turkey, partly due to the huge economic opportunities Turkey offers to the African business sector. However, some of those interviewed reported facing difficulties in acquiring residence permits to run their business legally in Turkey, especially in the current context of tightening policies towards foreigners in Turkey due to the ‘Syrian refugee’ effect and the socio-economic crises. Sometimes, African students work with Turkish partners to facilitate their residence and work permit process.

The courier companies owned by the African diaspora in Turkey mostly provide textile products, furniture, construction and building materials, iron, steel and medicine to Africa. In recent years, an increasing number of African students studying in Turkish universities, thanks to their sources or Turkish scholarship (YTB), seem to have been employed in such courier companies. On the other hand, whether the employment of African students in Turkey leads to a growing problem of abandonment of studies or research or not needs to be further investigated to measure the efficiency of Turkey’s educational policy towards Africa.

Another aspect relevant to African business people’s perceptions of Turkey is the production and the logistic performance of Turkish companies. Although the Turkish market does not always offer a business-friendly regulative atmosphere to foreign investors, African business people see comparative advantages in doing business with Turkish companies. Despite the language barrier and the current currency crisis of the Turkish lira, African business people are attracted by the resilience, flexible strategies and growing capacity of the Turkish market. The African business circles also perceive Turkish private-led construction companies as competent, cost-effective, trustworthy and competitive players, offering as many advantages to Africa as the Chinese construction firms. In the eyes of African business people, Chinese and Turkish companies are not rivals but rather partners with different capabilities. But African business people complain about the rise of transportation costs in Turkey, especially costs related to using Turkish airlines, although they seem to understand that this rise in prices is observed not only in Turkey but also in China and elsewhere as a consequence of the Covid and Ukraine crises. One interviewee said that, although other companies such as Morocco airlines or Ethiopian airlines are also operating the luggage transportation service from Turkey to several African countries at lower costs, their experiences with these companies had been bad in terms of loss of luggage. They, thus, seemed to prefer continuing to use the service of Turkish airlines for transporting their goods as it offered more security.

Whether Turkey’s growing African diaspora has been encountering discriminatory or racist attitudes in Turkey or not also constitutes an important aspect of African perceptions about Turkey. Since, approximately ten years ago, there were few Africans in Turkey as students or immigrants, Turks have always been curious about interacting with the unknown “black people”. As African students interviewed for this report stated, Turkish citizens’ attitudes towards African people living in Turkey has mostly been shaped by curiosity or strangeness rather than discrimination or fear. Most of the interviewees also observed that this curiosity of Turkish people generally turns to huge sympathy and positive discrimination, especially towards African children living in Turkey.

The Turkish government’s strong reaction to the presence of the Gülen movement in Africa following the 15 July 2016 failed coup d’état has had limited repercussions on African perceptions of Turkey. Indeed, the Gülen movement was heavily present in Africa, especially in the education sector with its schools opening in many African countries. Considering these schools as a potential means for the Gülen movement to consolidate its footprint in Africa and to build alliances against the Turkish government, the Turkish government started a courtesy campaign with African leaders to close the schools or hand them over to the newly created Maarif Foundation. An important number of African countries, including Tunisia, Morocco, Somalia, Sudan, Niger and Senegal, have sided with Turkey since the early days of the event and they have rapidly handed over the schools to Turkey. The Turkish government did not make use of coercive measures to get the schools closed or transferred to the Maarif Foundation. Rather, it prioritised soft measures as a sign of its respect for sovereignty of African countries, and this approach has also contributed to limiting the negative impact of the Gülen factor on Turkey-Africa relations. In this vein, the Gülen factor does not seem to play a decisive role in Turkey’s foreign policy priorities and orientations towards Africa, notably in the provision of aid and in economic relations.

In the education sector, most of the African students in Turkey interviewed for this project were relatively satisfied with their scholarship from the Turkish Scholarship (YTB Türkiye Bursları), although they did mention some limits. For instance, According to Fofana Cheick, a student of Civil Engineering at a Turkish state university and current president of the Association of the Burkinabe Students in Turkey (AEBT), the scholarship is comprehensive as it includes full tuition, insurance coverage and a sufficient monthly stipend. But he mentioned that the scholarship would have been better if Turkey could have included a round trip ticket to maybe the most successful students each year to allow them to go back to their countries for holidays, which will incentivise students to work harder. Some students also mention the added value of knowing the Turkish language and the fact that racism is not deeply felt in Turkey compared to other Western and Asian countries where African students study.

In Turkey, it is much more ignorance about Africa that has led to some situations where people on the streets are asking ‘nonsense’ questions about Africa. Some interviewees said that the fact that 90% of the Turkish population is Muslim has contributed to enhancing brotherhood feelings vis-à-vis foreign students. Other interviewees argue that, even though Turkish education is good, the Turkish government should make efforts in terms of bilateral cooperation with their African counterparts to facilitate the recognition process of the Turkish diploma in African countries. The current situation makes the professional integration of the African graduates from Turkish universities difficult and many direct them to self-employment upon their return to their countries.

Lastly, African think-tanks based in Africa have limited contact with Turkish think-tanks and higher education institutions. The Turkish side has made efforts to involve think-tanks and CSOs based in Africa in their Africa policy, such as the invitation of African think-tanks to participate in the 2022 Antalya diplomacy summit and the third Turkey-Africa Partnership summit held in Istanbul in 2021. However, these efforts seem to be limited in both scope and practice. The lack of strong connections between Turkish CSOs/think-tanks and African CSOs/think-tanks could be addressed by a dual engagement of two parties in launching activities such as student and scholar exchange programmes, joint curriculum development for undergraduate and graduate studies in African universities and joint research and scientific projects.

4. Turkey-Africa’s future relations: What is next?

In terms of projections of Turkey-Africa relations, four observations can be made. First, Turkish state officials and bureaucracies are strongly aware of the positive impact their “opening to Africa” policy has had on their country’s international visibility and prestige. Like its rising peers in the Global South, such as China, India and Brazil, Turkey also uses various instruments to upgrade its status in the changing international system. In this regard, its opening to Africa has been one of its foreign policy initiatives that has contributed to enhancing Turkey’s middle power actorship in the international arena. “The world is bigger than five” discourse of Turkish President Erdoğan has also been used by Turkish policymakers as a new role conception for Turkey as “defender of the oppressed”. Since Turkey’s “African” discourse and strategy have also been widely acknowledged by bureaucrats from the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a possible change of political regime at the top of the government would not lead to any structural change in the current dynamics of Turkey’s pro-active African policy.

Second, in light of how slowly FTAs are concluded, Turkey is likely to develop more flexible and tailored-made trade agreements with individual African countries. This slowness can be mostly explained by the fact that some African countries might still not be able to decide freely about the scope of their external trade engagements due to the persisting influence of the former colonial powers in the countries.

Third, Turkey could focus more on exploiting the human resource potential, essentially coming from African graduates from Turkish universities who have the advantages of speaking Turkish and being familiar with Turkish culture. Since Turkey claims that its approach towards Africa is singular and different from what has been observed so far from other external partners of Africa, putting African graduates at the centre of its foreign economic policy towards Africa might be an added value and contribute to anchoring this Turkish cooperation paradigm. In parallel, given that Turkey considers its approach to be people-centred with culture playing a key role, the country could leverage its engagements in the education and cultural sector through enhanced exchange programmes of both students and academics, increased cooperation at the level of higher education ministries and an increased number of scholarships awarded yearly. These initiatives will be the follow-up of the existing ones such as the establishment of the Maarif schools and Yunus Emre Institutes in several African countries.

Fourth, in the very short term, given that, in 2023, Turkey will experience one of the trickiest elections of its history and considering the worsening economic crisis in Turkey, one could predict that Turkey’s strategies and policies towards Africa will come under pressure for the next two to three years. These events, combined with the recent increase in Turkey’s defence expenditures, are consuming Turkey’s domestic capacities in terms of financial resources and might have a direct negative impact on the scope of Turkey’s engagement in Africa, especially in the field of development cooperation. It is more likely that the scope of Turkey’s ODA disbursement to SSA will diminish in the short term. But the volume of trade exchanges will continue to grow since Turkey’s domestic production capacity is increasing amidst the crises, and the fallout of the lira’s value (against many currencies in Africa) could incentivise African business people to buy more products from Turkey since those products would be cost efficient.

5. How can Turkey-Africa relations be leveraged to deliver gains for African countries’ agendas?

There are some requirements for Turkey-Africa relations to be leveraged to deliver gains for African countries’ agendas. First, in economic terms, it is important to remove the existing trade barriers between Turkey and most African countries. Africans are interested in Turkish products, hailed to be cost-efficient with the same quality standards as western products. But the double taxation at both Turkish and African countries’ checkpoints constitutes a sizable challenge to exploiting the existing potential in terms of trade. Turkey and African countries should move forward in their trade relations by concluding FTAs that will help intensify trade exchanges.

In terms of investment, it should not be one-way, meaning it should not be only Turkish people coming to Africa to invest; Africans should also start investing in Turkey to capitalise on the mutual gains. The few Africans who have invested in Turkey, especially in Istanbul, are all focused on the logistic sector (transporting goods from Turkey to Africa only), but the sectors of investment should be diversified. The same applies to Turkey, whose largest investors mainly focus on the mining sector. This focus should also be diversified and extended to sustainable job-creating sectors such as setting up firms and transferring technologies to transform Africa’s raw materials. It is also important for African countries to conclude agreements with their Turkish counterparts that would aim at easing the visa delivery process for African business people willing to travel to Turkey for business. Mutual investment protection agreements should be concluded between Turkey and African countries to reduce the burdens of administrative formalities and provide guarantees to the investors on both sides.

Second, African students who graduate from Turkish universities have great potential in leveraging Turkey-Africa relations because they have the advantage of knowing the Turkish language and the Turkish culture and people. Unfortunately, these potentials are not yet exploited by the African authorities, who sparsely integrate graduates from Turkey into their plans for Turkey. The Turkish side has made an effort to exploit these potentials, as is illustrated by the hiring of African students in Turkey-Africa business fairs held in Turkey. Since Turkey started to run the process of scholarships in 2012 unilaterally, African governments seem to have been frustrated by their exclusion from this process. Given the lack of digitisation of public services in many African countries, African authorities may not be updated about the number and identity of students benefiting from Turkish scholarships yearly. To remedy this situation, it is crucial for Turkey to cooperate further with the African governments in the scholarship process, and there is a need for both parties to enhance the cooperation between their ministries of higher education and ministries of foreign affairs. Turkish embassies in the recipient countries could also help inform the authorities in Africa about the outgoing and returning African students and their expertise.

Third, African countries should increase their ownership in their relations with Turkey in close cooperation with the African Union (AU). This increased ownership would mean that, instead of going individually with Turkey on several issues, African countries would gain more when they coordinate their actions through the prism of the AU, especially concerning several key issues such as FTAs. African countries should avoid duplicating the asymmetric relations they had with other traditional and emerging donors by not giving the entire financial burden to Turkey in their relationships. They should realise that they have as much to offer Turkey as Turkey has to offer them. Thus, they should maintain “an equal partner” basis in their engagement with Turkey because not depending financially on Turkey will allow them to have a voice at the table of discussion with their Turkish partners. African countries should enhance inter-African trade exchanges, which could be facilitated by the nascent African Continental Free Trade Area (ACFTA) and through investment in industrialisation policies that will help them diversify their export products. Turkish and African markets are growing markets with a huge potential that can be fully exploited, especially to Africa’s gain. However, the prerequisites are that African countries enhance their self-capacity in terms of production and increase the size of the African market through intensified intra-regional trade exchanges.

6. In Guise of Conclusion

Turkey-Africa relations have evolved to an unprecedented level in economic, political, cultural and security terms, as corroborated by the statistics and the interviews used in this report. The current economic crisis and the upcoming 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey might lead to a decrease in Turkey’s ODA to Africa in the short run. However, since African policy has gradually become an intrinsic part of Turkey’s foreign policy agenda over the last two decades, a significant change in Turkey’s African strategy is unlikely. Turkey’s African policy constitutes one of the new niche diplomacy areas for its foreign policy and a source for its prevailing status-seeking policies in world politics. In addition, Turkey’s African strategy has been widely appropriated by state agencies, including the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Ministry of Trade, TIKA, Ministry of Defence, Diyanet and non-state agencies such as CSOs actively engaged in the continent over the years. What makes Turkey’s African policy sustainable is closely linked to the question of “ownership”. This policy is not in a vacuum. In contrast, it has been formulated on a solid and long-term strategy to be implemented through strong cooperation and coordination among various state and non-state actors. Any change in Turkey’s political scene will not likely cause instability or uncertainty in the policy.

The 3rd Africa-Turkey Partnership Summit (16-18 December 2021) was a good indicator of the willingness of two sides to institutionalise further and diversify the relations by including new issue areas to the joint action plan from 2022 to 2026 such as “Peace, Security and Governance”, “Trade, Investment and Industry”, “Education, Science-Technology-Innovation skills, Youth and Women Development”, “Infrastructure Development and Agriculture” and “Promoting Resilient Health Systems”. The main topics of the summit gave strong signals about the priorities the two parties give to the future roadmap of their relations. In this regard, the Turkish-African future will more likely be centred around the following issue areas and their relevant discourses: peace, security and justice, human-focused development and strong and sustainable growth. Turkey’s relations with African regional organisations, most specifically the AU, seems to be gaining more importance in Turkey’s future interactions with Africa. The signature on the memorandum of understanding on cooperation between Turkey and the Secretariat of the ACFTA also showcases that the signing of new FTAs or the concluding of more flexible trade agreement modalities with African countries will likely remain a topical issue in Turkey-Africa relations.

In short, Turkey offers an alternative partnership modality to African countries, one which is likely to be more equal and win-win with a threefold perspective: trade, humanitarian and sustainable development cooperation and peace-building/security stabilising. On the other hand, there are significant differences in Africans’ perceptions of Turkey between people from NA and those from SSA, differences that can be justified partly by the complex historical relations North African countries had with Turkey under the Ottoman empire.

African stakeholders have an opportunity to leverage their relations with Turkey to their advantage. They should unify their capacities and open themselves to Turkey as a strategic partner to reach this goal. The AU should take leadership in Africa’s engagement with Turkey, especially by establishing institutionalised dialogue mechanisms.

Endnotes

The Cyprus issue can be traced back to the ejection of the Turkish Cypriots from the island’s government by the Greek Cypriot military junta in 1963. The objective of the Greek Cypriots was to start the process of unification with Greece, the so-called Enosis, a unification that was challenged legally by a treaty guaranteeing the independence of Cyprus. This ejection resulted in a UN presence on the island along the “green line”, which had been drawn to separate the two ethnic groups. However, Greek Cypriots did not scale down their Enosis project and continued with the ethnic cleansing of the Turkish Cypriots. The culminating year was 1974, when the Greek Cypriot military junta fomented a coup d’état to conquer the island for Greece. Five days later, Turkey reacted to this Greek Cypriot junta through a military intervention under the 1960 Treaty of Guarantee that had established Cyprus as an independent state. The end-result of these events was the de-facto division of the two communities on the island between the northern Turkish Cypriots and the southern Greek Cypriots, which contributed to halting the violence.

In March 2005, African countries issued their common position on the need to reform the UNSC through the African Union’s Ezulwini Consensus on the Reform of the United Nations’ Security Council. Through the Ezulwini declaration, they clearly raised their voice on the need to reform the UNSC and enhance the continent’s representativeness in this multinational institution.

Turkey occasionally provided budget support to only Somalia in 2019 (about 15.88% of total ODA to SSA in 2019).

Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). Importer/Exporter TIV Tables. SIPRI, 11 September 2022, https://armstrade.sipri.org/armstrade/page/values.php

https://www.sipri.org/publications/2022/sipri-fact-sheets/trends-international-arms-transfers-2021

The G-5 Sahel is a joint Force established by Burkina Faso, Niger, Chad, Mauritania and Mali (Mali recently withdrawn from the organisation amidst tense relations with ECOWAS, France, and its neighbours)

About the Authors

![]()

Emel Parlar Dal is a full Professor at Marmara University’s Department of International Relations (Turkey). She has more than twenty articles published in SSCI peer-reviewed journals, four edited books in Palgrave and she co-edited three special issues in Third World Quarterly, Contemporary Politics and International Politics. Her research interests focus among others on global governance, informality, middle powers, Climate policy, Multilateralism, International Development, Turkey-EU and Turkey-Africa relations. She is the director of the Jean Monnet Chair on the EU and Rising Powers in the Evolving Multilateralism for 2020-2023 and Jean Monnet Center of Excellence on the EU’s sustainability in Global Governance for 2022-2025.

![]()

Samiratou Dipama is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Law and Political Sciences at Thomas Sankara University (Burkina Faso). She published several articles in peer-reviewed SSCI journals including Contemporary Politics, International Politics, Global Policy, Alternatives and Uluslararası Ilişkiler as well as book chapters in Palgrave Macmillan and Routledge. Her current research interests include development cooperation, global governance, informal governance, EU-Africa relations, Turkey-Africa relations, democratization and security issues in Africa.