ATLANTA — There’s a lot of concern among Democrats about whether 81-year-old President Joe Biden is up to the task of either the presidency or defeating Donald Trump.

Past presidential campaigns offer lessons: None of them offer reason for optimism.

Going back to President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1968, several presidents who were eligible for reelection faced significant challenges in the primaries and questions about whether they should run again. George H. W. Bush, Jimmy Carter, and Gerald Ford all advanced and won the nomination, only to lose in November. Johnson chose to withdraw, ultimately costing the Democrats their election.

Biden never really fought the primary, but his allies now acknowledge how badly the president performed in the debates with Trump. They privately worry about whether Biden can hold the presidency until he’s 86 and, more immediately, whether he can beat a former Republican president to keep it. Biden himself is 78 and has a felony conviction, other charges and voter concerns about his values and character.

History is an ominous warning: Incumbent presidents who are still trying to ensure their party’s unity and security at this stage in their first term usually don’t get a second.

George H.W. Bush and the 1992 “Culture Wars”

Bush, an Ivy League-educated Episcopalian, was a moderate Republican and was never well-liked by the Christian right and anti-tax, small-government activists.

Prior to his victory in 1988, Bush appealed to the right by saying, “Read my words: No new taxes.” In 1990, the president was on a roll after swift U.S. military victories drove Iraq and Saddam Hussein from oil-rich Kuwait. But within months, Bush had broken his tax promises, the U.S. economy began to decline (albeit slightly in retrospect), and the president was weakened.

Primary challengers emerged, notably anti-tax crusader Steve Forbes and Christian conservative commentator Pat Buchanan. Bush won all of his primaries, but often by modest margins. Far from being an enthusiastic supporter of Bush, Buchanan used his Republican convention speech to enlist religious conservatives in a “culture war” against Clinton, liberals, and secularism. This is standard Republican rhetoric today, but it took a more divisive tone than Bush’s talk of a “kinder, gentler” nation.

Democratic candidate Bill Clinton, the governor of Arkansas, has blasted President Bush for being out of touch with middle-class Americans, and billionaire Ross Perot is running as an independent in the race.

On Election Day, 62.6% of voters voted against Bush. Clinton won 370 electoral votes, the second-highest total for a Democrat since 1964.

Jimmy Carter and Kennedy’s “Dream” of 1980

The former Georgia governor was a moderate Southerner from outside the liberal Democratic Party power structure, but his 1976 presidential nomination and victory over Republican incumbent Ford was not on ideology but on his promise to never lie to an American disillusioned by the Vietnam War and Watergate.

Despite continued legislative successes, Carter found himself antagonized by Democrats in Washington. Global inflation, U.S. unemployment and interest rates were rising, and Carter’s popularity was declining.

“Carter was not expected or accepted by the establishment,” said Joe Trippi, a member of Kennedy’s 1980 campaign staff.

Senator Ted Kennedy ran in the 1980 primary, inspiring young progressives who had idolized their slain brothers — former President Carter would say of Kennedy, “I’m going to blow his mind” — and, with the Iran hostage crisis adding to the crisis, the president won the delegates needed to secure the nomination.

But rather than trying to reconcile with the incumbent president, the defeated Kennedy used his convention speech to galvanize his supporters: “The work goes on, the cause goes on… and the dream never dies,” he declared, exposing Carter’s weakness.

Against Republican Ronald Reagan, Carter won just six states and Washington, DC.

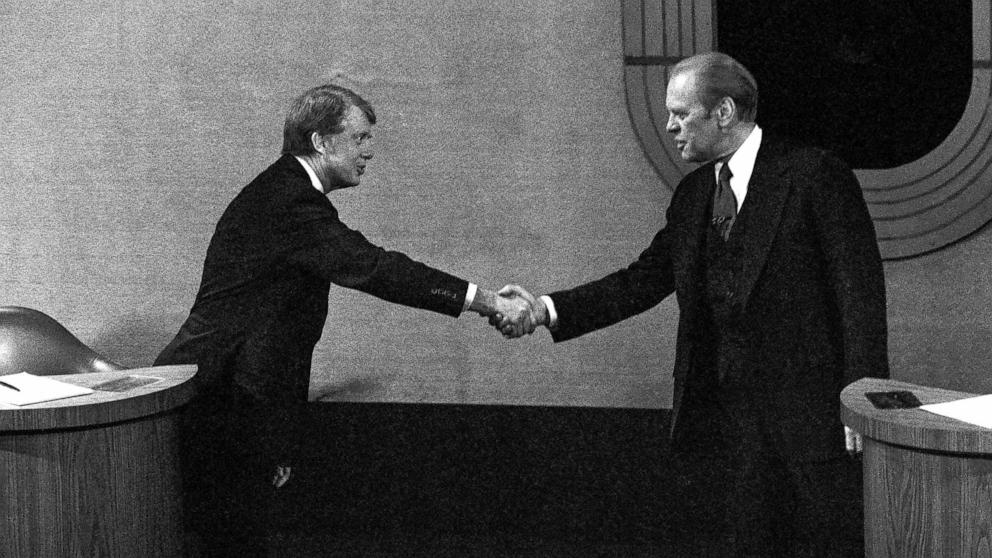

Gerald Ford and the Beginnings of the Reagan Revolution of 1976

Reagan won two general election landslide victories, but the basis for these victories was his challenge to Ford in the 1976 primary.

Ford, a mild-mannered Michigander, took a unique path to the White House: President Richard Nixon elevated Ford from House leadership to vice president after Spiro Agnew was forced to resign in 1973 for corruption allegations. Ford became president a year after Nixon resigned amid the Watergate scandal.

Ford had controversially pardoned Nixon, was facing inflation, high unemployment, turmoil in the energy markets, and, having never participated in a national election campaign, had to quickly organize his own.

Mr. Ford was a center-right Republican in Congress who had embraced most of the expansion of federal power since President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal, while Mr. Reagan embraced conservatives who had never embraced Roosevelt’s America and who were turned off by the civil rights and social revolutions of the 1960s and 1970s.

In the 1976 primaries, Ford won 27 precincts and Reagan won 24. This gave the incumbent Ford 1,121 delegates, just 43 more than his insurgent challenger. Reagan dominated most of the primaries in the South, the most conservative part of the country.

In the fall election, a bruised Ford made a late comeback against Carter, but it fell short: Carter carried the South, and Reagan would take over as Republican for another four years.

When the President Leaves Office: President Johnson and 1968

Ford, Carter and Bush aren’t entirely comparable candidates for the 2024 presidential race — Biden didn’t attract a credible primary challenger and there remains strong personal goodwill within the party despite the debate fallout — so perhaps the best comparison is to Johnson.

Following the assassination of John F. Kennedy, Johnson became president in November 1963. The colorful Texan, known as LBJ, defeated Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964. Johnson amassed the most expansive legislative record since President Franklin Roosevelt, including the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and Medicare and Medicaid. But Johnson also drastically expanded U.S. involvement in Vietnam and lied to the public in the process. He also found himself unable to lead the American people through the societal changes of the time.

Presidential campaigns were short at the time, so Johnson pondered his declining approval ratings and did not announce his intentions until March 31, 1968. After weak showings in the then-non-binding early primaries, Johnson said in an Oval Office speech, “I will not seek nor intend to accept the nomination of my party for another term as your President.”

But subsequent developments were not necessarily encouraging for Democrats who were hoping to hear the same from Biden.

Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York, who joined the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination race this year while his son, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., ran as an independent, gained momentum by winning California’s primary in June before being assassinated in Los Angeles minutes after delivering his victory speech.

The Democrats will hold a raucous convention in Chicago, which will also be the site of their 2024 convention. They have chosen Hubert Humphrey as their vice president to run against former Republican vice president Richard Nixon, who lost to John F. Kennedy in 1960 and also lost the 1962 California gubernatorial race.

Neither Nixon nor Humphrey were widely popular, and as a result the general election was closely contested with independent George Wallace being a key factor: Nixon won 301 electoral votes, about 500,000 more than Humphrey out of 73 million votes cast.

Seven months after an embattled Democratic president left office, his party suffered a defeat, and Republicans were back with a president-elect who would one day resign in disgrace.