Forty-five years ago, The New York Times provided a sharp analysis of the first three days of Pope John Paul II’s return to his Polish homeland. Reading the signs of the time from the common sense of the time, the paper offered a typical papacy-inspired editorial of June 5, 1979: “Pope John Paul II’s visit is sure to energize and inspire the Roman Catholic Church in Poland, but it does not threaten the political order in Poland or in Eastern Europe.”

Oops.

For one thing, the Polish Church of June 1979 did not need revitalization or reinspirement. It was the most powerful local church behind the Iron Curtain, the repository of Poland’s true national identity, and a constant thorn in the side of the Communist authorities. (Stalin famously said that trying to make Poland Communist was like trying to saddle a bull. He didn’t know that.)

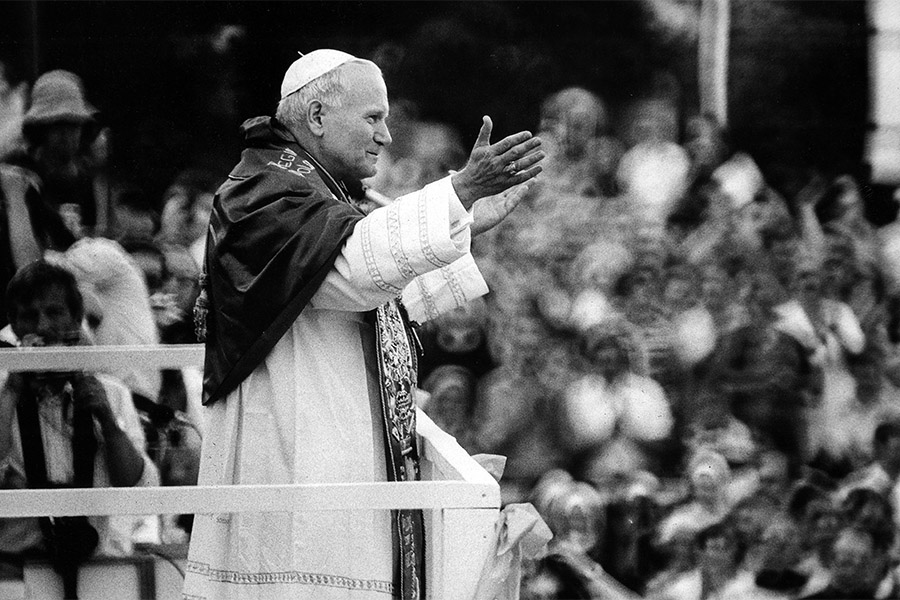

Speaking of the “national political order,” Polish Communist Party leader Edward Gierek secretly watched Pope John Paul II’s homecoming Mass on June 2 from a hotel room overlooking what was then Warsaw’s Victory Square. When the Pope called on the Holy Spirit to “renew the face of the earth, of this land” and he heard hundreds of thousands of Poles chanting “We want God! We want God!” he surely felt the winds of change blowing, even if New York’s anemometers didn’t measure a storm equivalent to Force 10 on the Beaufort scale.

And as for the “Eastern European political order,” Yale University’s John Lewis Gaddis, a leading American Cold War historian, wrote in 2005 that “when John Paul II kissed the ground at Warsaw airport on June 2, 1979, he began the process of the end of Communism in Poland and ultimately in all the rest of Europe.” I made that very argument 13 years ago in my book, The Last Revolution, in which I suggested that while there were many causes that shaped what became known as the 1989 Revolution, John Paul II was the essential factor determining when and how it happened.

What did he do and how did he do it?

What he did was ignite a revolution of conscience, which preceded and made possible the nonviolent political revolution that brought down the Berlin Wall, liberated East Central European countries, and, through the self-liberation of the Baltic states and Ukraine, brought about the collapse of the Soviet Union. The seeds of such a revolution of conscience, the decision of men and women to “live in truth,” in Vaclav Havel’s words, had been there for years in East Central Europe. Emboldened by the 1975 Helsinki Final Act and its “basket 3” human rights clauses, activists created organizations such as Charter 77 in Czechoslovakia, the Committee for the Defense of the Rights of Lay People in Lithuania, and KOR in Poland. [Workers’ Defense Committee] These were connected to the “Helsinki Watch Group” in North America and Western Europe. Pope John Paul II lit the fire and helped keep it burning by vocally supporting those who were taking “the risks of freedom” (as he put it at the UN in 1995).

How could this have happened?

John Paul II’s revolution of conscience began when he restored to the Polish people the truth of their history and culture that had been distorted and suppressed by the communist regime in Poland since 1945. From June 2 to June 10, 1979, the Pope advocated that “if we live in that truth, we will find the means of resistance that the violence of communism cannot match.” John Paul II did not invent those means; 14 months later, the Polish people formed a trade union called Solidarity, which later developed into a large social movement. But the heart and soul of the movement, like its namesake, was shaped by the ideas and witness of John Paul II.

The Pope’s friend, the philosopher and priest Joseph Tischner, once described the solidarity movement as a great forest planted by awakened consciences. Father Tischner’s beautiful image is one to ponder today, for the West needs a “reforestation,” a planting of new seeds of conscience that reflect the underlying truths about human dignity that John Paul II appealed to during those nine days in June 1979. Those were days when modern history was transformed, once and for all, in a more human and noble direction.

In Professor Gaddis’s words, John Paul II was one of those “visionaries” who, as a “disruptor of the status quo,” were able to “expand the range of historical possibilities.” Are there such visionaries among us today?

Read more

Copyright © 2024 Catholic Review Media

printing

printing