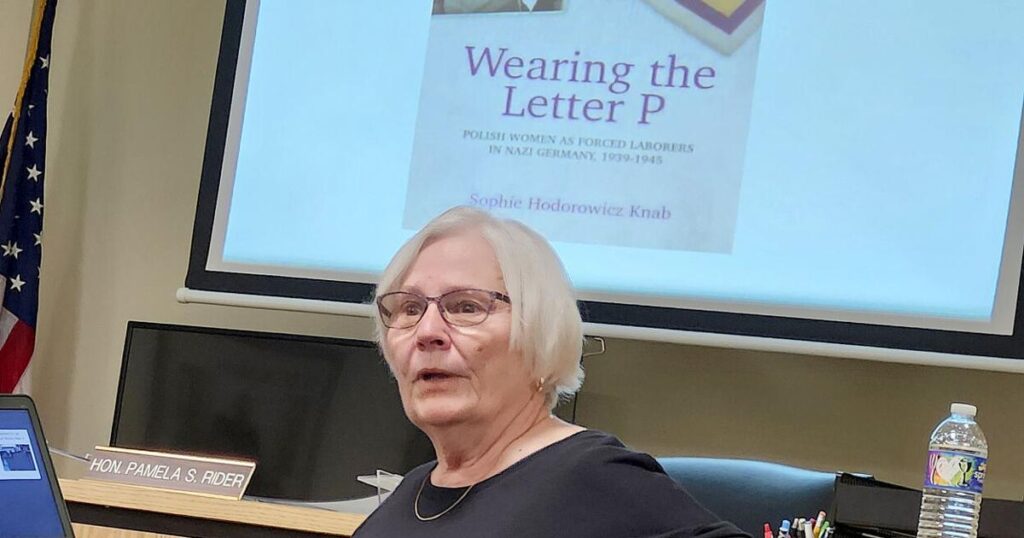

BARKER — Sophie Hodorowicz-Knab grew up in Dunkirk listening to her mother tell her stories of the atrocities she endured as a forced laborer in Germany during World War II.

Speaking as a special speaker at the Somerset Historical Society’s May meeting earlier this week, Nabb told the story of her family, who became forced labourers and eventually emigrated to the US after the war.

“My mother would talk about things that happened in her childhood all the time when I was growing up,” Nab said. “As I grew up, I realized this was my family history.”

Nabu took notes throughout his teenage years and early adulthood, but eventually he realized he had to study what his mother was talking about in order to write a book.

In 2000, at age 52, and after 14 years of research, Nabb began writing a book called “Wearing the Letter P.”

The title comes from the fact that in every country Hitler occupied during WWII, women (and some men) were abducted and forced to work in forced labor camps. Everyone was forced to wear a badge on their shirt identifying them as Polish, which meant they were useless and worthless. Anyone who sympathized with or fed the Poles was sent to a concentration camp.

Knab’s parents were Jozef and Josefa Zalewska-Jodorowicz. Jozef was forced to work early in the war, when the fighting was not as intense and the army did not need as many soldiers. He was sent to work at a shooting range near a German munitions factory, and later Josefa was sent there as well.

As a young woman, Josepha worked as a housekeeper for a wealthy American woman and thought she was safe there, but one day there was a knock on the door and two SS soldiers stood there with guns. They asked Josepha to come with them, but when she said she would bring her shoes, they told her she didn’t need them and took her away in just her dressing gown and slippers. Josepha was imprisoned until she was deported to Poland in early October 1943.

Knab said entire Polish population, men, women and teenagers, were forced at gunpoint into forced labor. About 500,000 women and 2 million Catholic men were sent from Poland to Germany, she said.

“They had no rights, but they received very little wages,” she said. “If they tried to escape and were caught, they were forced to do hard labor in concentration camps. The Germans controlled everything: food, industry. If they wanted to eat, they had to register to work for the Third Reich.”

“I’ve never lived in an occupied country so I don’t know what it’s like to have every aspect of your life controlled,” Nab said. “Guns and cameras were confiscated. People were stuffed with all their belongings into pillowcases and shoved onto trains.”

In Krakow, some were maimed, tortured or killed before being sent to transit camps, where thousands were crammed into buildings meant to hold 200. In one such building, Nab’s mother described how doctors sat at tables and women were made to walk around naked while the doctors examined them to see if they were healthy enough to work.

Tuberculosis was widespread and mortality was extremely high, Nabu said. People were crammed into cattle cars, with buckets in corners or holes in the floor serving as toilets.

Because Hitler wanted to increase his race, babies were screened for German characteristics and separated from their mothers, who were sent back to work three days after birth.

The barracks where they slept were full of bedbugs.

Those who became sick were sent to psychiatric hospitals where they were euthanized.

Nabu’s older brother, Michael, was born in a labor camp and near the end of the war, a munitions factory was bombed. Josepha started to run to the nursery in the barracks and grabbed Michael. She ran as fast as she could.

“She knew if she could get to the woods she’d be safe,” Nab said. “She spent the night in the woods.”

57 children died in the bombing and are buried in the town’s cemetery.

Nab, who now lives in Grand Island, visited Poland in 2004 and discovered the factory where his mother worked.

“Fifty-nine years later, I find myself face to face with evidence of that day that has lived on in my mother’s memory all her life,” Nabb said.

Nabu’s brother, Andrew, was born in a refugee camp, and Nabu was born in Hanover, Germany, and she has an aunt who survived Auschwitz.

After the war, his father decided he had no intention of remaining in the country that had mistreated him, so he took his family to France to find work, and then decided to emigrate to the United States.

“You can go to America if you have someone there to sponsor you,” Nab said. “My mother had an uncle in Dunkirk and she wrote to him. I’ve always felt great pride in America and in a few weeks I’ll be celebrating my 70th year in the United States.”

After settling in Dunkirk in 1954, Nab went to Buffalo to attend nursing school, where she met her future husband, Ed.

Nabu said everyone should put their life story on paper so that future generations can read it.

“Every story in life matters,” she said.

Her books are available from Amazon, SUNY Niagara, and possibly some libraries.