BESA Center Perspective Paper No. 1,509, March 29, 2020

Summary: The deaths of 290 Turkish soldiers fighting on Syrian soil in recent years are a grim reminder of the unresolved issues that continue to sour relations between the two neighbors even decades later.

Turkish soldiers have been killed with alarming frequency on Syrian soil over the past few years: 17 were killed in Syria before Euphrates Shield, and another 72 during that operation, which lasted from August 24, 2016 to March 29, 2017; 96 during Operation Olive Branch (January 20, 2018 to August 9, 2019), 16 during Operation Peace Spring (October 9 to November 25, 2019), 14 after that operation, and 75 during the current Turkish operation in Idlib province.

Turkey-Syria hostility is a long-standing element of modern Middle East politics. It is always there, though sometimes obscured by other regional trends and events. Of the 22 member states of the Arab League, only Syria has recognized the Armenian genocide (though Lebanon eventually did).

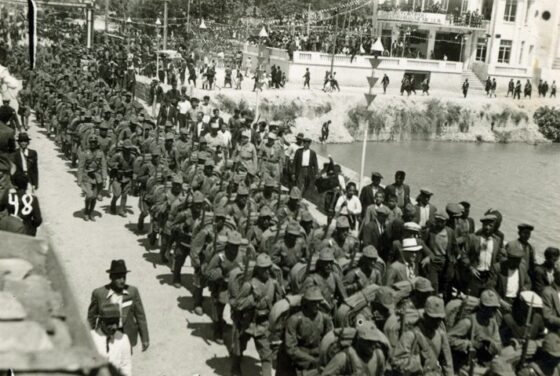

This mutual hostility has deep roots. Between 1918 and 1921, a series of clashes took place on Turkey’s Güney Çefesi (“Southern Front”), between French, Arab and Armenian forces invading from Aleppo and Idlib in northern Syria on the one hand, and the Turkish national army led by the Grand National Assembly government in Ankara on the other. At stake was control of Adana, Mersin and Cilicia.

In 1936, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk demanded that the Syrian town of Alexandretta and the surrounding area be handed over to Turkey on the grounds that the majority of the people living there were Turkish. A complaint was filed with the League of Nations, setting off a series of events that led to Turkish military units entering Alexandretta on July 5, 1938, and annexing the area as Turkey’s 63rd province. To this day, Syria considers Alexandretta to be part of its territory and marks it as such on maps. On Turkish maps, the area is called Hatay.

Syrian politicians and officials have refrained from speaking about the Alexandreta/Hatay issue for many years. Any Syrian official or politician who mentioned the issue was barred from entering Turkey for any reason. Since Turkey shares a border with Syria and has been the main destination for Syrian tourists for many years, the risk of being blacklisted by Turkey was too high for Syrian officials. Due to the silence of Syrian officials and media on the Alexandreta/Hatay issue, the Syrian public is unaware that this issue even exists. This is different from, for example, the Golan Heights, which the Syrian government and media always refer to as the “occupied Syrian Golan.”

Since the creation of Syria in 1943, Turkish people have considered it, along with Lebanon, Jordan, and Israel, a state founded on the ruins of the Ottoman Empire. Turks have never forgotten the collaboration between the Arabs and the British Empire that led to the collapse of the Ottoman Empire. As long as Turkey had nationalist (i.e. secular and separatist) governments in the country, it kept its distance from the Arabs, who were widely despised for their role in the collapse of the empire. However, the rise of Islamists to power (Necmettin Erbakan in 1996, Recep Tayyip Erdogan in 2003) led to greater collaboration with the Arabs, since most Arabs are Muslim.

Arabs in the Middle East are generally not inclined to trust Turkey because they continue to harbor dark memories of the Turkish-Ottoman rule. They remember the Turks torturing them by beating their feet with kurbaji (whips), hanging them on mashnaka (gallows) or making them sit on kazuk (bayonets) and ripping out their internal organs. The memory of 400 years of Ottoman oppression (1517-1917) is deeply ingrained in Arab culture.

Erdogan has adopted a neo-Ottoman approach towards lands that belonged to Turkey until World War I, including Syria, Lebanon, Jordan, Israel, Egypt, Saudi Arabia and Iraq. Hegemony over these countries was, and remains, the ultimate goal of his Middle East policy.

Cooperation with the Syrian regime was a given at one time, since Syria was Turkey’s main export base to Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the Gulf countries. Hostility towards the Kurds was also a commonality between the Turkish and Syrian regimes. The good personal relationship between Erdogan and Bashar al-Assad led to an agreement allowing visa-free mutual visits between the citizens of both countries, a rare phenomenon in the Middle East.

But the honeymoon ended in March 2011 when the so-called Arab Spring plunged Syria into a bloody civil war between a government led by the minority Alawite sect and the country’s Muslim majority. Erdogan felt he had no choice but to support Muslims against the Alawites, whom Islam considers infidels.

In 2014, Turkey supported ISIS by allowing ISIS volunteers to pass freely across the Turkish-Syrian border, buying Syrian oil from ISIS, and allowing ISIS militants to use Turkish territory for tactical purposes. Ankara also granted asylum to over three million Syrian refugees, most of whom are Muslim, which put an enormous strain on the Turkish economy.

Erdogan watched as Syrian, Iranian and Russian forces pounded the city of Aleppo, but could not do much to support its Muslim residents at the time.

Now Erdogan is taking revenge on the Assad regime by attacking the Syrian army, occupying parts of Syrian territory bordering Turkey, and encouraging Syrian Sunni Muslim refugees to return to Syria, where he is doing all he can to expel them forever and replace them with Shiites from Iraq, Iran and Afghanistan.

Turkey’s transition from nationalist regimes (Atatürk, İsmet İnönu, Celal Beyar and their successors, civilian and military) to Islamist regimes added another layer of hostility to deep-rooted and long-standing nationalist tensions based on border disputes, religious animosities and dark historical memories between countries.

View PDF

Colonel Dan Gottlieb (Ret.) is a graduate of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Bar Ilan University School of Law. He has served four tours of duty in various parts of Africa and is the Israeli Medical Association’s leading expert on African issues.

Dr. Mordechai Kedar (Ret.) is a Senior Research Fellow at the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies. He served in the Israel Defense Forces Intelligence for 25 years specializing in Syria, Arab political discourse, Arab mass media, Islamic groups, and Arabs in Israel, and is an expert on the Muslim Brotherhood and other Islamist groups.