It has been revealed that much of the loot returned to Turkey and Italy over the past three months was from the personal collection of prominent American philanthropist Shelby White. The items were seized from Mr. White’s Manhattan home over the past 18 months as part of a long-running investigation into the origins of his collection.

Search warrants issued by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office on June 28, 2021, and April 27, 2022, reviewed by The Art Newspaper, include search warrants issued by the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office on June 28, 2021, and April 27, 2022 that indicate that Homeland Security agents believe to be stolen property. There are 5 and 18 works listed for which there is a reason, respectively. They constitute evidence of first-, second-, third- and fourth-degree criminal possession of stolen property and conspiracy to commit those crimes, according to the documents.

Matthew Bogdanos, head of the Manhattan prosecutor’s antiquities trafficking division, declined to comment because the case is ongoing. White also declined to comment, telling The Art Newspaper: “I really don’t have anything to say.”

White is a major donor to institutions such as the Metropolitan Museum of Art, where he is a director and director, and New York University, where he founded the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World through a controversial $200 million gift in 2006. Together with her late husband Leon Levy, who now runs the foundation that bears her name, she built a collection of ancient art representing the ancient Near East, Greece, Etruscan, Roman, and other cultures. White and Levy donated $20 million to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which in 2007 named its monumental gallery of Greek and Roman art the Leon Levy and Shelby White Court.

This is not the first time the Levy-White collection has come under scrutiny for allegations of looting. In 1990, more than 200 objects from the couple’s collection were exhibited at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in “Past Glory: Ancient Art from the Shelby White and Leon Levy Collection.” A decade later, archaeologists David Gill and Christopher Chippindale published a study that found that 93 percent of the works in the exhibit were of unknown provenance. In 2008, White handed over 10 classical antiquities to Italian authorities and two 4th century BCE works to Greece. In 2011, the upper body of “Weary Hercules,” a statue jointly owned by Levy, White, and the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and featured in “Past Glory,” was returned to Turkey.

Part of an Anatolian columnar sarcophagus excavated from the ancient city of Perge. Dating from around 170 to 180 AD.

Courtesy of the U.S. Consulate General, Istanbul, via Facebook

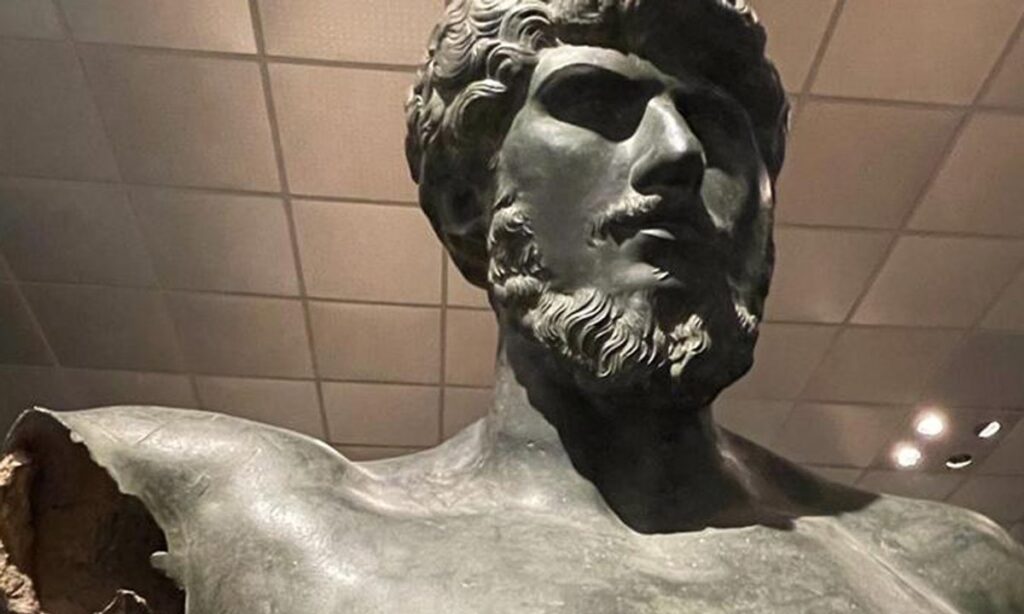

Among the works seized in recent restitution efforts are several featured in the Past Glories catalog. In October, a joint restitution effort between the Manhattan District Attorney’s Office, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, and Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism returned to Turkey a life-size bronze statue of Roman Emperor Lucius Verus (dated to the late 2nd to early 3rd century) and four pieces of a columned sarcophagus from the ancient Anatolian city of Perge, made between 170 and 180. An April 27 search warrant for White listed the statue at $15 million and the sarcophagus fragments at $1 million.

Both pieces were unveiled on November 13 during a handover ceremony at the Antalya Museum, along with four other looted items, including an early Bronze Age marble Khusla statue and a statue of Apollo. The artifacts were taken from an illegal excavation site in Turkey and smuggled into the United States more than 50 years ago, according to the U.S. Consulate General in Istanbul. The Harriet Daily News identified the previous owners of the six works as two U.S. auction houses and an anonymous collector.

But Mr Gill, an emeritus professor at the University of Kent’s Heritage Centre, was quick to link up with Mr White and mention the objects featured in Past Glory on his blog Looting Matters. Gill also published a list of objects formerly in the Levy-White Collection that have been returned to date. Many of them were identified by his former student Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist and antiquities trafficking expert at the Ionian University in Greece, who has sent photographic evidence to the Manhattan DA’s office.

The list of looting issues includes the names of antiquities seized from White’s apartment this year and returned to Italy in September: a Gatus from Apulia with a sheep’s-head spout (c. 330 B.C., valued at $15,000); two fish plates attributed to the Ika Painter and the Perrone Phrixus group of painters (mid-fourth century B.C., valued at $20,000 each); and a “bronze bust of mankind” (1st century B.C., valued at $3 million); a cauldron with four animal heads (6th century B.C., valued at $150,000); and a bronze spiral brooch formerly owned by White (value: $25,000). They were among 58 antiquities returned by the Manhattan DA’s office in September, including 21 from the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

At least one more item was also returned to Italy, including a ceremonial dinosaur from 700 BC that was seized from Mr White’s collection under a June 2021 warrant. It is one of about 200 looted Greco-Roman artifacts recovered from museums and homes across the United States in December 2021, and authorities say it is the largest single repatriation of artifacts from the United States to Italy. It was described as the largest scale.

White’s name has not yet appeared on the official return notice, but Gill expects further announcements to come from the Manhattan district attorney’s office. “I think it’s very significant that they’re not saying it’s Shelby’s,” Gill said of the returned artifacts. “So this is obviously part of a much larger investigation…There are items that have been returned to Italy and Turkey. I believe there are also items that are destined for return to Greece.”

He added that museums should exercise caution and properly evaluate any future loans from the White & Levy collection. “Obviously, they acquired a number of items that were illegally excavated and taken from their countries of origin outside of a legal framework,” he said. “They will say they acquired them in good faith, but given the scale of looting that we know about, they should have done their due diligence before acquiring them. Museums need to exercise due diligence in accepting loans.”

But Tsirogiannis says he’s not optimistic that museums will change their ways. “Antiques markets and museums do the same thing as collectors. They don’t check their items with the authorities. Rather, they try to hold on for as long as possible, thinking they might somehow get away. “I’m trying to do that,” he says. “But the reality is that, even if they probably don’t want to realize it, they’re waiting for the inevitable that authorities will come knocking on their door with a warrant. It’s up to them whether they follow this strategy or not. It’s a choice, but you already know this won’t work and you need to change your attitude.

“The recent incident involving the Shelby Whites collection is further evidence of this point.”