In contrast to the deadlocked land war, Ukraine’s tactics in the Black Sea have dealt Russia humiliating defeats, with Turkey emerging as the sea’s maritime power

The Russian warship Moskva, the flagship of the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet, is shown in a 2013 photo. Ukraine struck and sank the Moskva with two Neptune anti-ship missiles on April 14, 2022. © Getty Images

The Russian warship Moskva, the flagship of the Russian Navy’s Black Sea Fleet, is shown in a 2013 photo. Ukraine struck and sank the Moskva with two Neptune anti-ship missiles on April 14, 2022. © Getty Images

×

In a nutshell

Ukraine’s strikes have forced the Russian Black Sea Fleet to retreat

As Russian naval prowess wanes, Black Sea power dynamics have shifted

Turkey, the gatekeeper of the sea’s naval traffic, has gained the upper hand

A major consequence of Russia’s strategic miscalculation in attacking Ukraine is unfolding in the Black Sea. Turkey stands to be its greatest beneficiary.

In contrast to the land war between Russian and Ukrainian forces, which, Ukraine’s recently dismissed commander-in-chief General Valery Zaluzhny, had famously declared to be in a stalemate with no prospects for any “beautiful military breakthrough,” the dynamics in the Black Sea are changing. Russia is on the losing end as its large-scale invasion approaches the two-year mark on February 24.

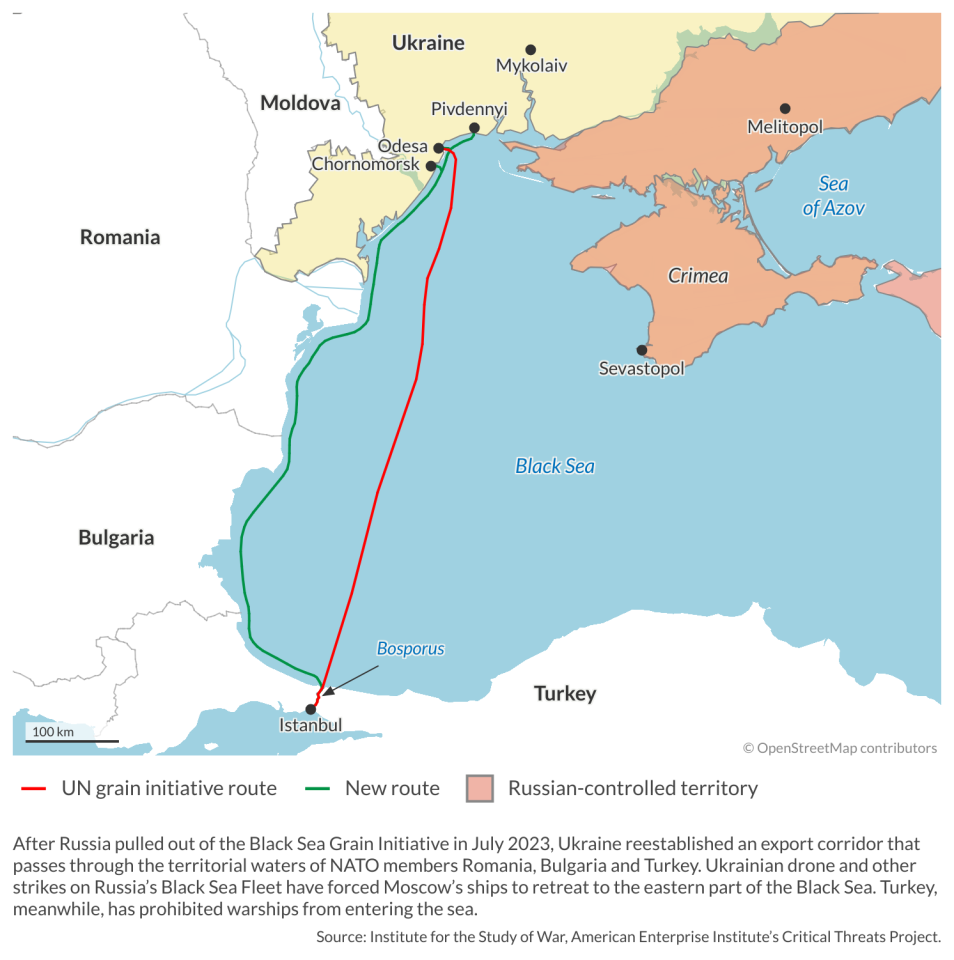

By using Western-supplied cruise missiles and through ingenious attacks with automated weapons systems, Ukraine is defying the odds. So far, it has been remarkably successful in punishing the Russian Black Sea fleet, forcing it to assume a defensive posture and even retreat eastward. To make matters worse for Russia, Ukraine has scored another victory by reestablishing a shipping corridor hugging the western shores of the Black Sea and eventually transiting through Istanbul to export its grain, something Russia was desperately trying to prevent. This route has been largely successful, reaching an export volume not seen since the Russian invasion, and compensating for Ukraine’s losses from the collapse of the grain corridor agreement, brokered by the United Nations and Turkey, that Russia had walked out of in July 2023.

What is truly surprising is that Ukraine is turning the tide against Russia in the Black Sea, though it barely has any navy to speak of. Russia’s inability to prevent these developments in the Black Sea has tarnished its swagger. Moreover, its loss of critical platforms, including its flagship Moskva, amounts to an actual degradation of Russian naval capabilities in the Black Sea. This problem is compounded by the fact that, for now, it is next to impossible to replace these assets.

Besides being militarily (and financially) overstretched, Russia cannot deploy any new battleships in the area. Since the onset of war in Ukraine, Turkey closed its straits to transit of military vessels whose home base is not in the Black Sea, under Article 19 of the Montreux Convention. With this move, which senior American officials describe as “a very important contribution to Ukraine’s security,” naval traffic has since been suspended in and out of this inland sea.

Russia retains substantial naval capabilities in the Black Sea, but its downward trajectory poses a two-dimensional problem for Moscow. As the war drags on and Ukraine sustains its offensive operations in the Black Sea, which they brazenly vow to do, Russia’s naval supremacy will erode. This, in turn, will shift the balance of power in the regional maritime domain in Turkey’s favor as it comfortably watches these developments from the sidelines.

This is a risky forecast that is bound to preoccupy Russia. In contrast, Turkey and its allies, foremost the United States, will see it as an opportunity. Turkey will view it as a convenient way to gain the upper hand in the Black Sea, while the U.S. (and other NATO members) will welcome the weakening of Russia, described in NATO’s Vilnius Summit Communique last year as “the most significant and direct threat to Allies’ security and peace and stability in the Euro-Atlantic area.”

As the struggle in the Black Sea evolves, and each actor tries to shape developments in its favor, the role of one stands out in every conceivable scenario: Turkey, the gatekeeper of the Black Sea.

Turkey’s Black Sea game

The importance that Turkey attaches to the Black Sea is very high. It is a crucial sea for connectivity, including for energy pipelines, and has lately become the venue for Turkey’s flourishing indigenous natural gas extraction activities. This has accentuated Turkey’s security-focused approach to the region and increased its motivation to hold an exclusive role. The main drivers currently behind Turkey’s approach to security in the Black Sea can be summarized under three headings: Russia, the U.S. and the Montreux Convention.

×

Facts & figures

The Russia-Ukraine war at sea

The Russian connection

Turkey and Russia’s main theater of competition has historically been the wider Black Sea region, where Russia made gains in the 18th century. This legacy of conflict undergirds a sense of awareness on both sides that they are nemeses from imperial times.

This backdrop informed top Russian military officials as they were gloating in 2016 about their country’s supremacy over Turkey in the Black Sea. That same year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made a similar revelation when he lamented that the Black Sea had become a “Russian lake” and advocated for a greater NATO presence in the region.

Both statements came a year after Turkey had shot down a Russian fighter jet over the Syrian border. Bilateral relations had not been repaired yet, and Turkey’s perception of the threat from Russia remained high. Moreover, Turkey’s relations with the U.S. and its Western allies were stable and had not yet become fraught.

Things started to change on both counts after the 2016 coup attempt in Turkey. Russia quickly reached out to support the Turkish leadership, starkly contrasting the muted approach of the U.S. and most NATO allies. The atmosphere between Ankara and Moscow quickly improved as the countries’ presidents deliberately chose to cultivate a personal relationship, paving the way for a new era in Turkish-Russian bilateral relations. The two nations settled into a pattern characterized by deepened cooperation amid managed rivalry in places like Syria, Libya and the Southern Caucasus.

Today’s seemingly cozy atmosphere between Turkey and Russia belies the pervasive competitive undercurrent characterizing their relations. This dynamic was evident, for example, in Russian President Vladimir Putin’s infamous speech in 2022 designed to justify the invasion of Ukraine. Part of his concocted narrative rested on Russia’s conquests of the Ottomans in the Black Sea region, including Crimea.

Historical realities and regional dynamics make Turkish-Russian relations complex. Seeming contradictions and the need to manage them are part of the relationship and something both parties are well versed in. Turkey’s approach to the war in Ukraine is an excellent example of this. It was supplying Ukraine with weapons systems and vocally supporting its territorial integrity long before the war began. While not deviating from this position after the outbreak of hostilities, Turkey carefully refrained from burning bridges with Russia and, most notably, did not join the sanctions regime. Russia, too, chose to overlook some of its disappointments with Turkey’s policies and go along with its balancing act.

“Neither friend nor foe” might be the most appropriate way to describe how these two countries approach each other nowadays. The same mindset guides their posture against one another in the Black Sea. While there is no flagrant confrontation on the surface, the sense of rivalry and desire to gain the upper hand at the expense of the other is permanent.

The American connection and the Montreux Convention

Turkey benefits from the balancing effect of the U.S. and other actors against Russia but expects this to happen on its terms. The Black Sea is, after all, Turkey’s historical backyard. The actions of non-littoral states should not be destabilizing or deliberately provocative in a way that could lead to a regional conflagration with Russia. And the Montreux Convention should be strictly adhered to.

Yet, Turkey is distrustful of the U.S. on both counts. This is primarily a function of its deep-seated grievance toward the U.S. for its interventions and policies in Iraq and Syria, which have come at a significant cost to Turkey’s economic and security interests and continue to this date.

Turkey is also concerned about the U.S.’s approach to the Montreux Convention. When Russia attacked Georgia in 2008, the U.S. attempted to deliver humanitarian aid on naval vessels that grossly exceeded the tonnage restrictions stipulated in the convention. This was seen as a deliberate and ill-intentioned attempt to violate the terms of the convention, fueling Ankara’s suspicions.

Turkey reflects its distrust toward the U.S. in its approach to NATO’s role in the Black Sea. This visceral reflex sometimes leads to overdosed statements like a recent one from Turkish Navy Chief Admiral Ercument Tatlioglu. Talking about the threat of mines in the Black Sea, he said Turkey would do what is necessary and added that Ankara did not want to see the U.S. or NATO take additional measures in these waters. The irony, of course, is that Turkey itself is a longstanding NATO ally and has already undertaken the demining task with its Black Sea NATO allies Bulgaria and Romania.

×

Scenarios

Three scenarios are possible, of which only one is likely.

Unlikely: Russia forces Turkey’s hand and augments its naval presence

Russia failed in its aim of turning Ukraine into a landlocked country through military pressure. And now, Russia finds itself on its back foot in the Black Sea, seeking refuge in the east and desperately trying to preserve its existing capabilities. To reverse this trajectory and put its existing naval platforms to better use, albeit at the risk of losing them, Russia needs to be able to augment its naval presence in the Black Sea. But Turkey has shut that door, and though Russia tested its resolve on several occasions by insisting on the right to transit the Turkish Straits, Ankara did not budge. Moreover, if Turkey were to capitulate to Russian demands, that would also open the door for non-littoral states to send naval assets into the Black Sea, further disadvantaging Russia. Moscow would think twice before going there. Hence, this is an unlikely scenario.

Unlikely: The U.S. (and NATO allies) press for access

While the impact of Turkey’s decision to suspend the transit of naval vessels to and from the Black Sea has gained praise in Ukraine and among its supporters, it has also had the reverse effect of precluding the arrival of external naval support for Ukraine. It may, therefore, seem tempting to insist that Turkey reverse its decision.

But Turkey has been diligently implementing the Montreux Convention since 1936, which it considers the bedrock of security and stability in the Black Sea. Moreover, this legal instrument not only gave Turkey the duty to govern transit passage in and out of the Black Sea but also confirmed its full sovereignty over the straits. Hence, the Montreux Convention has added meaning for Turkey.

Any assumption that it might risk undermining the integrity of the Montreux Convention would be misguided, making this scenario unlikely. And in any such unlikely scenario, while Russia would also gain the right to augment its naval presence in the Black Sea, the probability of naval assets from non-littoral states getting embroiled in kinetic action with Russian forces would increase, as would the risk of the conflict widening. Neither the U.S. nor other Western actors seem inclined to take such a risk.

Likely: The status quo continues and Turkey benefits

The most likely scenario is for Turkey to firmly continue its suspension of naval vessel transits to and from the Black Sea while the state of war continues, depriving Russia of the ability to bring in new capabilities and obliging it to stay on the defensive in the maritime domain. This will incentivize Russia to maintain its primary focus on warfare on land, where it will hope to wear down Ukrainian resilience and Western support in a war of attrition. In the meantime, Russia will keep a hopeful eye on upcoming elections in the U.S.

The true beneficiary of the situation in the Black Sea will be Turkey. Russia’s gradual decline in naval power at the hands of the Ukrainians will raise Turkey’s standing as the dominant naval force. Even better for Turkey, this gradual evolution will take place without any potentially destabilizing actions by non-littoral actors like the U.S., as their assets will continue to be unable to access the Black Sea.

For industry-specific scenarios and bespoke geopolitical intelligence, contact us and we will provide you with more information about our advisory services.

Sign up for our newsletter

Receive insights from our experts every week in your inbox.