This is part of Slate’s 2024 Olympics coverage. Read more here. If you enjoy our coverage from Paris, please support our work by joining Slate Plus.

As part of efforts to reduce the Olympics’ carbon footprint, Olympic chefs are incorporating plant-based dishes both in athletes’ cafeterias and at the venues, with Flige urging fans to “Veni, Vidi, Veggie!”

But merchants at Rungis, the giant wholesale market that supplies much of the capital’s food, have their own ideas about Olympic performance. “This is exactly the perfect food supply for the marathon,” Véronique Girard said, shucking her namesake oysters as the last buyers loaded trucks at 4 a.m. one morning last week. “They’re cold and fresh.”

In the frigid meat section next door, butcher Caroline Fauchère, who has fished out hundreds of cattle, sings the praises of beef: “Traditionally, beef is part of French cuisine. Entrecote frites, everyone knows it. We have Americans who come from all over the world to eat French steaks. After all, we say ‘strong as a bull,’ so it would be a shame to be strong as a bull and not eat beef.”

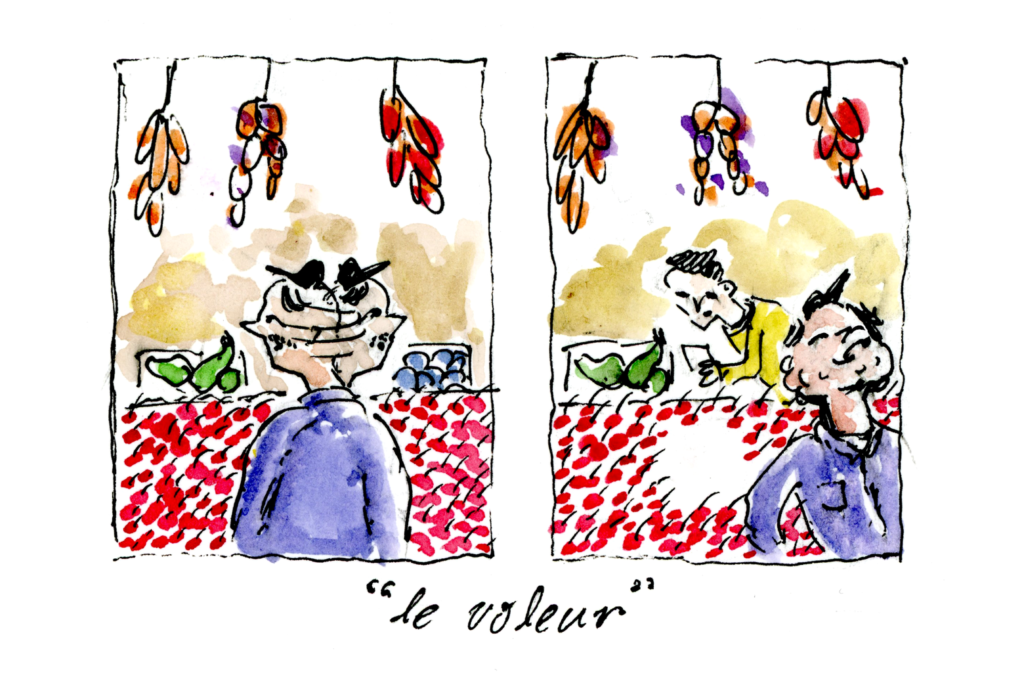

Illustration by Logan Guo.

From the head of state’s gala on Thursday to the Olympic Village, from fashionable restaurants to suburban fishmongers, tiny grocers and neighborhood street markets, a good deal of what’s edible in Paris comes from Rungis. Rungis claims to be the world’s largest fresh-food market, and the metropolis, which stretches across 570 acres near Orly airport, is home to 13,000 employees and 18 restaurants. (Note: These are different from meat refrigerators, which are open to the public.)

Rungis Market, like others like it, is busiest just before dawn. Chefs and retailers wander the long halls, traditionally exchanging two kisses with suppliers in the nine halls devoted to seafood, flowers, meat and vegetables. Wholesalers in forklifts yell orders as they wheel pallets through the maze. In the market’s largest fresh produce department, buyers cycle between mountains of peaches, tomatoes and melons, efficiently comparing purchases between halls. Each “pavilion” is more than 600 feet long and is separated by huge truck bays.

In the dairy department, which smells like a Swiss cheese hole, I meet Thierry Guillard, who runs a shop near Paris, as he does his weekly grocery shopping. “When you buy clothes, you try them on,” he says. “It’s the same with cheese.” You can tap the handle of your pocket knife against a wheel of Comté to gauge the structural strength of the cheese; if it’s a block of Sakura chèvre, all you have to do is remove the lid and inspect the inside.

Of course, these days many people don’t try on clothes before they buy them. Veterans in the meat and fish department say foot traffic to their departments has started to decline with the rise of the internet and the faster-paced, more connected world that comes with it. Arnaud Vanhame, who works for seafood wholesaler Raynaud, says the market’s function as a trading space is fading. “The customers are the same, the sales are the same, but we don’t see each other as much,” he laments. “It’s the Uberization of society.”

Rungis was founded in 1969 at the crossroads of highways, railways, and airports, when it moved from congested Les Halles in central Paris. Many Parisians thought of the move as like a baseball team moving to the suburbs, since the central market had been in the same place in Paris since the 12th century. The destruction of Les Halles is remembered as a kind of urban tragedy, like Paris’s version of New York’s Pennsylvania Station or Boston’s West End.

This sense of nostalgia has two sources that are not entirely logically compatible: on the one hand, a longing for the city as a place of production, manual labor, and the culture that goes with it; on the other, regret for the relegation of those tasks and the people who performed them to the urban periphery. Émile Zola’s novel The Belly of Paris evokes this lost world in poetic detail: “The warm afternoon sun softened the cheese, melting the mold on the rind, leaving it burnished with a deep coppery patina, like a wound that does not heal. Under the oak leaves, a gentle breeze seemed to lift the skin of the olives, moving up and down in time with the slow, deep breathing of the sleepers.” A diorama of a grocer in the chapel of the neighboring Saint-Eustache church depicts them as exiles, but their carts are loaded with cabbages rather than possessions.

Illustration by Logan Guo.

On the other hand, the grand Grocery Hall, of iron and glass with its delicate metalwork and flying buttresses, the product (along with the famous boulevard) of Napoleon III’s urban renewal programme, is nothing short of architectural regret: not only were they graceful and innovative structures in their own right, but, with similar structures adopted a few miles away in the Parc de La Villette, they can easily be imagined today as galleries, concert halls, offices and other spaces of the post-industrial city.

Clearly, these two nostalgia are incompatible. The wholesale markets would not have been able to survive without modern infrastructure, but eventually Paris lost both its market and its building, and markets in other cities followed suit: New York’s Fulton Fish Market moved to the Bronx in 2005, and Tokyo’s Tsukiji now holds its famous pre-dawn tuna auctions further away on reclaimed land in the bay.

But Rungis is no soulless modern substitute: It’s a close-knit social network of sellers and buyers who have worked together, in some cases for generations (Vanhamme is a third-generation fishmonger; Faucher works with his father). Older Rungis employees remember when the younger ones were children.

Even if the internet has diminished barter and vast walking journeys with digital checklists, Rungis remains the region’s food storehouse. You can’t fill a truck online. Paris and its surrounding communities have a vibrant network of small merchants selling exceptionally high-quality groceries and meats, cheeses, and vegetables because buyers have access to a state-of-the-art wholesale market at their disposal. (As a New York resident, parallels to the dysfunctional Hunts Point Market spring to mind.)

Henry Glover

A rainy, rowdy party on the Seine

read more

Another threat to Rungis is the rise of French chain supermarkets such as Auchan, Leclerc, and Carrefour. The largest chain is Intermarché, which employs over 150,000 people and currently operates more than 1,800 stores. Most of these chains have American-style stores, but with slightly larger cheese selections, slightly less parking, and are located on the outskirts of French towns and cities. Each of these chains has its own supply chain, making them the de facto retailers for most cost-conscious French buyers. These chains have also caused and exploited the decline of commerce in France’s small towns. The suburban, motorway-adjacent shopping districts that have sprung up around these chains now account for more than 70% of French household spending.

America’s new number one song has done something even Beyoncé couldn’t do. Who would have thought that this former Friends member would have one of the most fascinating careers ever? Headlining the Olympic Opening Ceremony – the glory or the deep heartache? The competitive, athletic, wildly popular sport that the Olympics can’t touch with a 10-foot pole?

Interestingly, Rungis, a classic example of the suburbanization of central urban activity, acts as a bulwark against the commercial activity of the main streets that give Paris its unique atmosphere.

On Thursday morning, a group of journalists breakfasted with Rungis’ president, Stéphane Lajani, at a market café. Dressed in a crisp blue suit and tie, Lajani insisted on accompanying his meal with organic Côtes du Rhône. Waiters brought croissants, pain au chocolat, strawberry, cherry, cantaloupe, smoked salmon tartine, grilled chicken, rare steak, and, to finish, tête de veau. It was just after 9 a.m.

As he prepares for a gala dinner at the Louvre with Emmanuel Macron, Jill Biden and Mohammed bin Salman (catered by Runjis), Rayani cites many factors working in Runjis’s favor — buying local, buying organic, understanding supply chains — and says there are no factors working against it, such as the cost-of-living crisis that has driven much of the recent conflict in French politics. “The trends are good.”

So Stephen Lajani isn’t worried. How could he be worried after a breakfast like that?

Illustration by Slate.

Source link