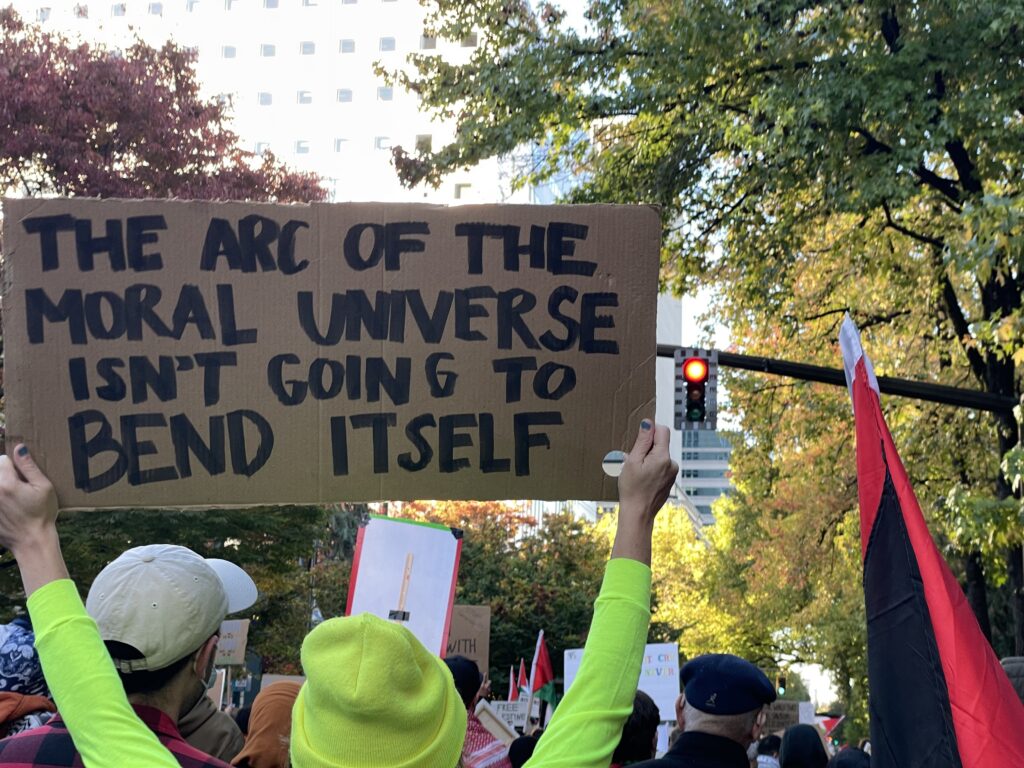

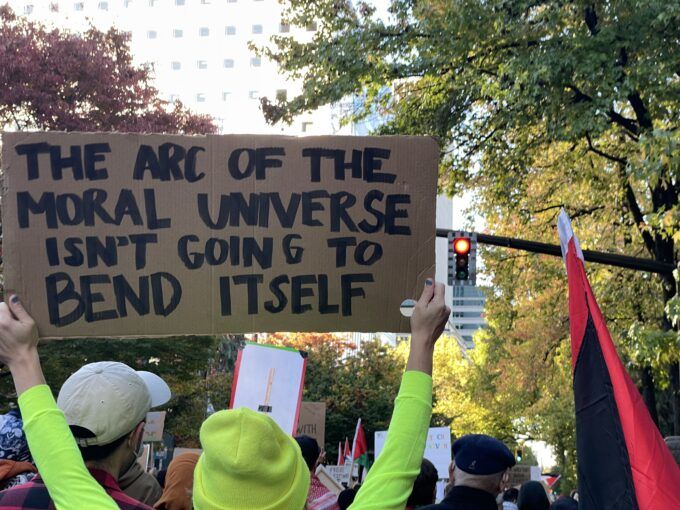

Photo by Nathaniel St. Clair

Yesterday, there was a funeral for my mother, Karen Saum. She passed away on May 9th. She was 89 years old. She was a woman with a strong fighting spirit.

My mother lived in the international melting pot of Colon City, Panama’s Caribbean coast, from the time she was born in 1935 until her senior year of high school. Her father was an engineer for the Panama Canal. At the time, most American families lived in the Canal Zone, but her family did not. Although they lived on the Panama mainland, my mother attended school in the United States.

The house maid was from Jamaica, a descendant of Caribbean slavery. Her name was Clementine. In the old, faded photograph, I saw a big, strong woman. She was a woman who made a lasting impression on my mother. For her, it was an innate lesson about colonialism that you could never learn from a book. And it stayed with me.

My mother graduated from Mount Tamalpais High School in Marin County, just north of San Francisco, and went on to Stanford University, where she met my father, who was teaching at Stanford.

A few years after our two sons were born, my mother was just 24 when my father was fired from his teaching position at George Washington University for his Communist Party affiliation while attending Harvard Graduate School. She sat beside him as he testified before the House Un-American Activities Committee, and my brother Peter and I sat on her lap, a long way from the Panama Canal.

My mother then nearly completed her dissertation in history at Johns Hopkins University, all the while raising her three sons. I don’t know when she began protesting the Vietnam War, but it was some time before the assassination of President Kennedy on November 22, 1963, ruined the 29th birthday of my mother’s new partner, Linda Simmons. Simmons was an architect who later became president of Phipps Houses, New York City’s largest nonprofit housing construction company. Linda died on February 8, three months and one day before my mother.

My mother’s first Vietnam protest was attended by only six people, including me, and this was years before the anti-war movement became a major force in the United States.

From there, my mother became immersed in the civil rights movement, marching across the South with King and Kwame Ture (then Stokely Carmichael), and watching the conflict that escalated between the radical King and the even more radical Stokely.

My mother didn’t just study history; she lived it and she taught it. She taught at Brooklyn College and Manhattan College in the 1960s. History burned brightly in New York City, in the South, across the country, and around the world.

In 1968, my two brothers, my mother, and her new partner sailed with the Holland America Line from Montreal to Southampton, England, where we rented a Volkswagen camper bus that would become our home for the next year as we traveled around Europe.

We were in Florence on November 5, 1968, when Nixon beat Humphrey by 0.7 percentage points, casting a pall over our visit to this great, 2,000-year-old city, and when we arrived in Greece on a ferry from Italy, my mother admonished my brothers and I not to speak ill of the military junta that had taken power in Greece the previous year and would rule the country until 1974. In Vienna, my mother sent my brothers and me to the Viennese public school, even though we didn’t speak a word of German.

We took a boat to Alexandria, Egypt, and then a train to Cairo, passing farmers pulling oxen to irrigate their fields, as they have done for thousands of years.

Less than a year after the Six-Day War, sandbagged machine gun nests were common in the streets of Cairo. In Giza, my brothers and I rode camels past the gigantic, 2,500-year-old pyramids, a mind-blowing experience for a 10-year-old me.

After our trip to Europe, my siblings and I moved to Charlotte, North Carolina to be with my father, and my mother moved to Maine, where she would live for the rest of her life for the next 55 years. She taught at the University of Maine at Augusta (UMA) until she was quietly fired for a variety of reasons, including her Vietnam War activism, gay rights activism, her own sexual orientation, and her radical and unconventional teaching.

My mother eventually found her way to the HOME Co-op in Orlando, Maine. HOME Co-op is a community by and for the rural poor of Maine, on the northern frontier of Appalachian poverty. It was founded by Lucy Poulin, a former Carmelite nun who took the gospel fight for the poor seriously. Having been raised Catholic, my mother had finally found a home.

My mother founded and ran the Rural Education Program (REP) at HOME Co-op, a groundbreaking program that gave rural poor people, especially women and single mothers, the opportunity to go to college. At her funeral, held yesterday in the HOME Co-op chapel, a longtime friend of my mother’s told the story of how she bailed her out of prison and enrolled her in REP, and how it changed her life.

Another attendee, a Vietnam veteran and a former student of his mother’s at UMA more than 50 years ago, described the role she played in his radicalization and how she corresponded with him during the 18 years he spent in the hellish dungeons of the federal supermax prison, much of it in solitary confinement, and how her letters helped him get through.

My mother spent her life on the front lines of history and social change.

I can barely count the number of times my mother told me in the latter years of her life that she feared she would never make it to heaven because she had never spent a night in prison.

Well, I think that feeling is enough. In fact, I think it is. Goodbye, mom. We miss you. And I really wish there were more people like you.