Brisa Ellis, president of the Adair County Historical Society and Museum

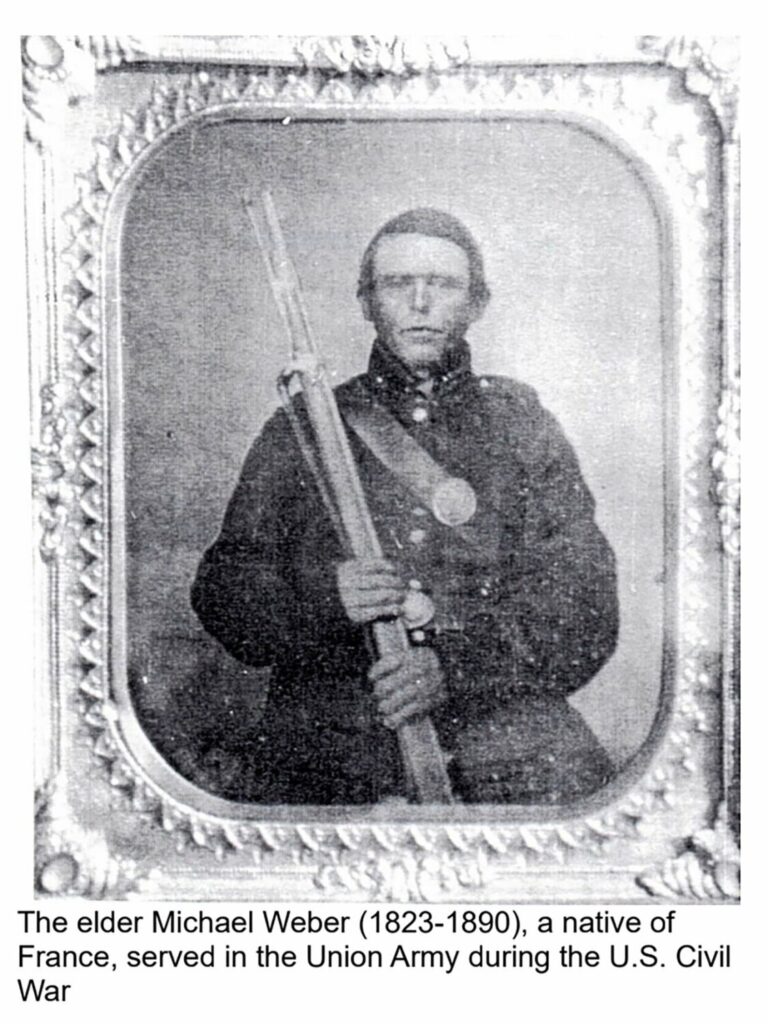

As we learned last week, Michael and Magdalena (Spielmann) Weber left France in 1847 when their son Michael was three months old. They were tired of the war in their home country and didn’t want their son to become a soldier and join an endless war. Unfortunately, his older brother Michael found that the New World was not a place without war either. Fourteen years after leaving France, he found himself faced with a war not of conquest, as Napoleon had done in France, but of countrymen fighting countrymen in the US Civil War.

Michael Weber and his family spent 11 years in Ohio before moving to Missouri in 1858. The Webers are listed on the 1860 census as living in Apple Point, Liberty Township, Adair County, Missouri. Michael was 38 and Magdalena was 35. They had five children at this time: little Michael was 13, George was 10, Philip was 8, Mary Eva was 5, and Jacob was 2. They should have had six children. Their daughter Elizabeth, who was 9 years old on this census, is not listed. We can only assume she died, but the record does not say when.

It is clear that Michael believed in the values of his adopted country, as when the American Civil War broke out, he enlisted to save the Union. He served in Company H, 2nd Missouri State Militia Cavalry, and Company C, 11th Missouri State Militia Cavalry. He was fortunate to survive the war and return to his family in Adair County.

After the 1860 census, two more children were born to the Weber family: Magdalena “Lena” in December 1860 and Sarah Elizabeth in September 1866.

Young Michael grew to manhood in Adair County, working on his father’s farm. He later stated that in those early days the first plowing was done with oxen and a wooden plow. He said that wild ducks were seen in flocks by the hundreds, and that there were more wild turkeys in the farm yard than chickens. Deer were so numerous in those days that they were once seen being driven into the barn yard with the cattle.

Michael was 15 years old when the Battle of Kirksville took place on August 6, 1862. He later stated that he heard the sounds of guns and cannon fire from his father’s farm near Nind during the fighting.

In 1867, at the age of 20, young Michael married Eva Haas, daughter of his neighbor George Jacob Haas Sr. (1824-1895). Eva was born in Bavaria and came to the United States with her family in 1853. She and Michael were married for 13 years, but there does not appear to be any record of them having any children. Eva died of unknown causes on May 17, 1880, and is buried in Mount Carmel Cemetery near Yarrow, Missouri.

A year later, young Michael married Magnolia Florence Hayes, the daughter of Civil War veteran Harrison Faith Hayes and Rachel Jane (Waddill) who lived in the same area as the Webers. Magnolia was the oldest child in the family, her mother having died when she was 13. Her father remarried, and Magnolia had brothers and sisters and half-brothers and sisters who she undoubtedly cared for.

Back when the Webers came to America in 1847, a family from Switzerland had just settled on the east side of the Chariton River in Adair County, about 10 miles southwest of Kirksville. This was the family of John A. Dumy, whose wife was Ann Mariah “Marie” (Pfister) Dumy. (The surname is also spelled Domey and Doomy, but John and Marie’s gravestones read Duemy.)

In January 1847, the couple was living in Ohio and had just welcomed their first child, Daniel Dumy. Later that year, they moved to Adair County, Missouri. John Dumy, a miller by trade, was looking to set up a flour mill business. He had applied for and received permission from the state to build a dam on the Chariton River. He also built a one-story flour mill with a powered wheel under a portion of the building that overhangs the river’s edge.

John Duemy operated a successful flour mill at this location for seven years, and a small village grew around his mill, hence the name.

The Duemys had two children, Roseanne, born in 1849, and Louise, born in 1851. Sadly, John Duemy died of unknown causes on October 11, 1854. He was buried in what later became Yarrow Cemetery (then called Pierceville Cemetery). The 1860 census lists John’s wife Ann Marie’s occupation as miller, so it appears she continued to run the mill herself, with the help of her son Daniel, who was 13 at the time, or by using hired help.

The mill was later sold to a man named Dr. Johns and then to an Englishman named John B. “Yankee” Williams, who renamed the business Williams Mill. The mill was destroyed in the mid-1870s when a flood caused the original building to collapse and be washed downstream. Mr. Williams rebuilt the mill in 1876, giving it three stories. As Mr. Williams was primarily a lumber merchant, the mill included a sawmill. A young Michael Webber, then 29 years old, helped build the mill. The 1880 Adair County census lists John B. Williams and his family as living in Pettis Township and his occupation as miller.

In 1882, a new bridge was built over the Chariton River at Williams Mill and was called the Lower Iron Bridge. At this time, the bridge and the nearby village of Williams Mill had no name (it later became Yarrow, but this name was not heard until 1903). What was once the village of Duemy’s Mill is now more often called the Lower Iron Bridge or Williams Mill.

Just a mile away was the hamlet of Linderville. Reverend James Harvey Linder came to the area from Ohio in 1854 and established a store, school and church. Linderville’s post office was officially established in 1865 after the Civil War. (For a more detailed account of Linderville, see Part 67 of this history series.)

Many believed Linderville would become the commercial center of the region until the railroad arrived in 1903 and changed everything, but we’re not there yet – we’re still going back 20 years.

In December 1882, John B. Williams was selling land in order to move to Arkansas. He advertised in the Kirksville Graphic an auction to be held “Tuesday, December 26th, at his home, Williams Mill, near the New Bridge.” For sale was “a large amount of lumber, five horses, two mules, five dairy cows, fifteen sheep, numerous hogs, one wagon, three wagons, farm implements, hay, corn and household goods.”

According to some articles, Mr. Williams continued to own the mill until he eventually sold it to his brother, Michael Webber, in 1890. An August 1890 article in the Kirksville Daily Journal states that Michael Webber “purchased the Linderville Mill a few weeks ago.” This is confusing, as the Williams Mill was not previously called the Linderville Mill. However, we do know that Michael Webber purchased the mill featured here.

After purchasing the mill, Michael moved his family to the mill community and built a large two-story house on a hill just a short distance from the mill, which became the Weber Mill.

© Copyright 2024 Blytha Ellis