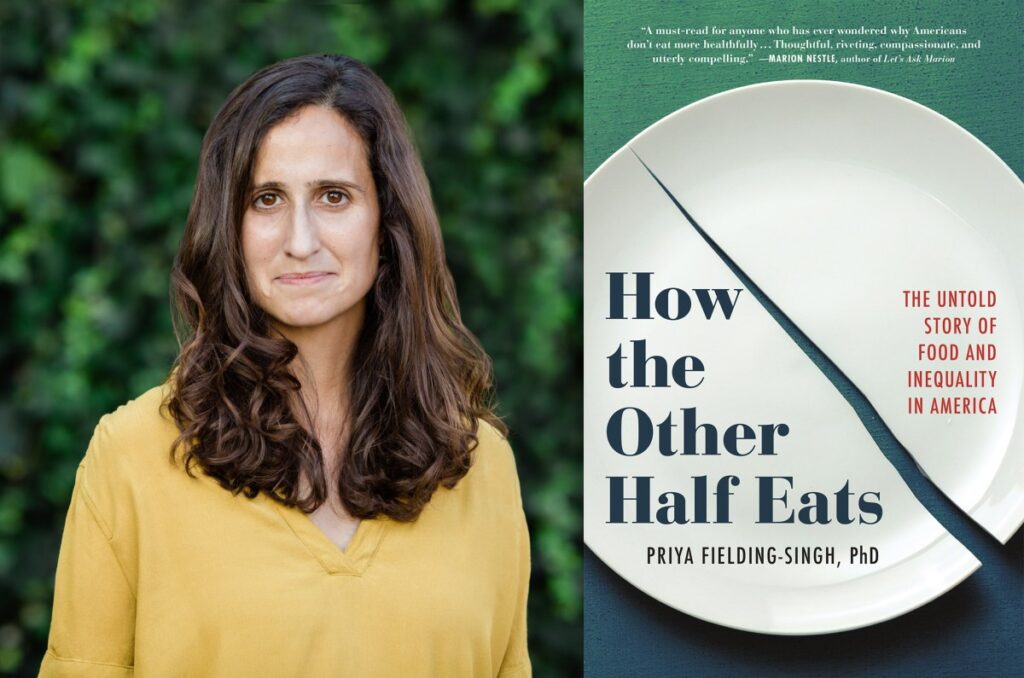

My family, friends, and the entire This Is Uncomfortable team could barely enjoy a meal without talking about something I learned from Priya Fielding Singh’s How the Other Half Eats.

Did you know that collard greens and kale (and the exact same species, Brassica oleracea) are nutritionally equivalent, yet racism and social prejudice have led to one being promoted as a superfood over the other?

Sociologist Fielding Singh interviewed 75 diverse families in the San Francisco Bay Area to get a broad picture of how Americans feed their families and why there are such persistent nutritional disparities between the rich and the poor.

“How the Other Half Eats” is the culmination of three years of research, but it’s not a boring, academic read. The book focuses on the four families Fielding Singh accompanied, who are so relatable that I could see myself shopping, cooking and eating with them for weeks on end. She learned a lot about the symbolic value of food and the anxieties mothers of all income levels face.

I love that these personal stories are the foundation of the book, and they remind me of how our show tries to tackle big economic issues through personal stories. I called Fielding Singh a few weeks ago to talk about this, and here are some excerpts from our conversation:

This Is Uncomfortable: How would you describe this book for someone who hasn’t read it yet?

Priya Fielding Singh: My motivation for writing this book was to explore the phenomenon of nutritional inequality – the disparity in dietary quality between the rich and the poor. We have a very good grasp of the breadth of this problem – how many people it affects, and the dire and disturbing consequences of this kind of inequality – but we have a much shallower understanding of how this inequality actually affects people’s lives. How do people make difficult, complex, and sometimes contradictory choices about food that extend into these broader inequalities?

So as a sociologist and as a qualitative researcher, I felt really motivated and prepared to use a human-centered lens to really spend time with families, parents, and children who are on the ground laboring, working, and making choices. A key goal of the book was to illuminate how difficult those choices are, and what that means, sometimes in surprising ways, about how inequalities play out on a larger scale.

TIU: Was there anything in your research that particularly surprised you?

Fielding Singh: I think there’s an assumption that low-income families don’t actually know what’s healthy or don’t value healthy foods, but I can’t emphasize enough how wrong this assumption is. Nearly all of the mothers I interviewed for the book wanted their children to eat healthy foods, understood that healthy eating is important for their children’s health, and had a broad understanding of what healthy foods are. So nutrition education isn’t the main barrier here. What surprised me was how mothers across the income spectrum varied so much in the way they fed their children because of the symbolic meaning that food holds.

Food not only has material value to us, but also has enormous symbolic value: what we eat, for example, is deeply connected to our place in society, which shapes what food means to us, how we use it to show affection to others, to uphold traditions, and to understand who we are and what we value. Right?

TIU: From what I’ve read, you intended to write a book about food inequality, but it ended up becoming a project about mothers and food. Was that something you expected?

Fielding Singh: No, I wanted to focus on families because I wanted to understand both the food and diet aspects. But once I started interviewing for this project, a few months into it, it became clear to me that this is a study of the unspoken and often undervalued labor of mothers, the role that mothers play, the idea of what it means to be a good mother, and how food and nutrition are connected to mothering and parenting. It was a story that really needed to be told, because it’s a story that nobody in the nutrition or public health field had told. Not just the women who are doing this work and making these choices, but the women who are struggling to fit into societal definitions of what it means to be a good mother.

TIU: You write about “intensive parenting,” a term I had never heard before. Can you explain it?

Fielding Singh: In the United States, there are such deeply shared beliefs about what makes a woman a good mother that sociologists call it the “ideology of intensive mothering,” a term coined in the 1990s by a sociologist named Sharon Hayes to describe the unreasonably, unattainably high standards held up for mothers in this country.

A “good mother” must act as the primary guardian for her children, which is labor intensive and resource intensive. A “good mother” is self-sacrificing, putting her children’s needs before her own. And what really matters is that “good mothers” are typically portrayed as white, married to men, and wealthy. Yet even though it’s out of reach for most American mothers, research shows that mothers across society actually aspire to an impossible standard: intensive parenting. So mothers look for ways to feel like they’re good mothers.

So through my work, I noticed that low-income mothers use food for two purposes. First, they use food to nourish their children emotionally in times of hardship, to protect them from scarcity and adversity. But they also try to prove to themselves that they are good mothers, that they can bring a smile to their children’s faces even in the face of deep poverty. And that’s why I use this concept of intensive parenting in a lot of the book, because it’s so important to understanding mothering behavior and the ways in which mothers of different incomes try to love and care for their children through food.

TIU: In the book, one of the low-income mothers, Nya, gives her child money to buy ice cream. Those two dollars don’t pay off her credit card debt or lift her family out of poverty, but they make her daughter smile and make Nya feel like a good mother.

Fielding Singh: Right. What struck me as I spent time with low-income mothers was that so much of their experience raising children has been about saying no. No to this, no to that. It’s so traumatic for the child and for the mother to have to say no over and over and over all the time. So it’s really quite a challenge to find something that’s relatively affordable and has such a huge impact on a child’s well-being. And that’s junk food in this country.

TIU: Speaking of which, you’ve written that class influences not only our eating habits but also our perceptions of other people’s eating habits. Can you explain that?

Fielding Singh: Yes, there is a double standard. So when wealthy, especially white, moms feed their kids, say, a bag of Cheetos, we judge them as not being overly dominant. They’re laid-back, they’re cool. So that’s good. But when low-income moms do it, they’re deemed neglectful, careless. They’re either ignorant or they just don’t care or don’t value what their kids should be eating. So it’s really amazing how the exact same food can generate such wildly different social evaluations.

TIU: I was really surprised reading the book to learn that even the most affluent and privileged mothers feel extremely stressed and feel like they’re not performing well enough or doing enough to provide for their families in a healthy way. Why do you think this is?

Fielding Singh: Yeah, that really struck me too. I learned that mothers across all income levels feel some level of guilt or anxiety about how they feed their kids, and that most mothers engage in what sociologists call “emotion work” to alleviate that guilt. So by “emotion work,” I mean the inner work that each of us does to monitor, evaluate, suppress, or shape our emotions in certain ways. Emotion work isn’t just about trying to project the right emotions outwardly, but about actively trying to manage the emotions that arise inside. So, for example, trying to turn disappointment into gratitude.

But I found that mothers at all income levels used very different strategies to shape their feelings as determined by their socioeconomic status: low-income mothers engaged in what I call downscaling, pushing aside guilt in an attempt to accept and reconcile. In contrast, high-income mothers often took the opposite approach, engaging in what I call upscaling, escalating guilt by raising already high and unattainable societal standards for intensive parenting.

And I realized that mothers across society share this oppressive sense of guilt. No mother escapes this labor unscathed. But you’d think that having more money or more time would give you the privilege of maybe not having to worry. But in fact it was the exact opposite. And it was a really interesting reflection of how money can affect our eating habits in unexpected ways.

TIU: Since you began this project, you’ve become a mother yourself. I’m curious how this research has influenced your own approach to food. Fielding Singh: Witnessing the level of guilt and anxiety that mothers feel around food has helped me approach this experience with a little more awareness and a little more perspective. It’s also made me more grateful for the resources I have and the time I have to work with food, to approach it with less guilt and stress, and to be a little more forgiving and grateful towards myself.

📚Recommendations for the next Uncomfortable Book Club📚

In two weeks, we’ll be talking with linguist, podcaster, and past TIU guest Amanda Montell about her new book, The Age of Magical Overthinking. It’s a quick read that fits into the self-help theme we covered last season. Have you read it? Send us your thoughts and we might include them in the conversation.

Comfort Zone

What our team is working on this week

There’s a lot going on in the world, and Marketplace is here for you.

Marketplace helps you analyze world events and bring you fact-based, easy-to-understand information about how they affect you. We rely on your financial support to keep doing this.

Your donation today will help power the independent journalism you rely on: For as little as $5 a month, you can help sustain Marketplace and continue covering the stories that matter to you.