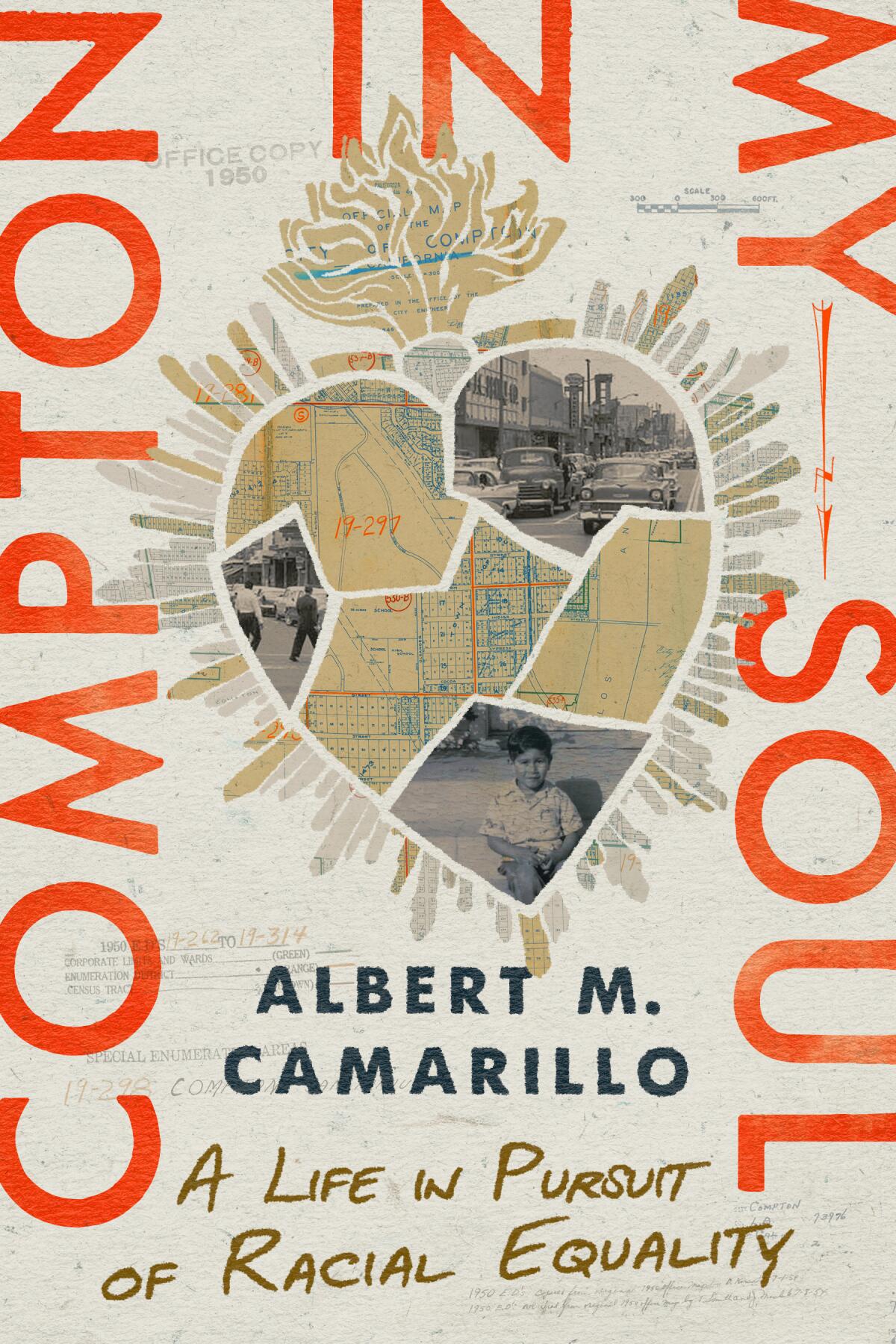

Book Review

Compton on My Mind: A Life in Pursuit of Racial Equality

Albert M. Camarillo

Stanford: 312 pages, $28.

If you buy a book linked to on our site, The Times may receive a commission from Bookshop.org, which helps support independent bookshops.

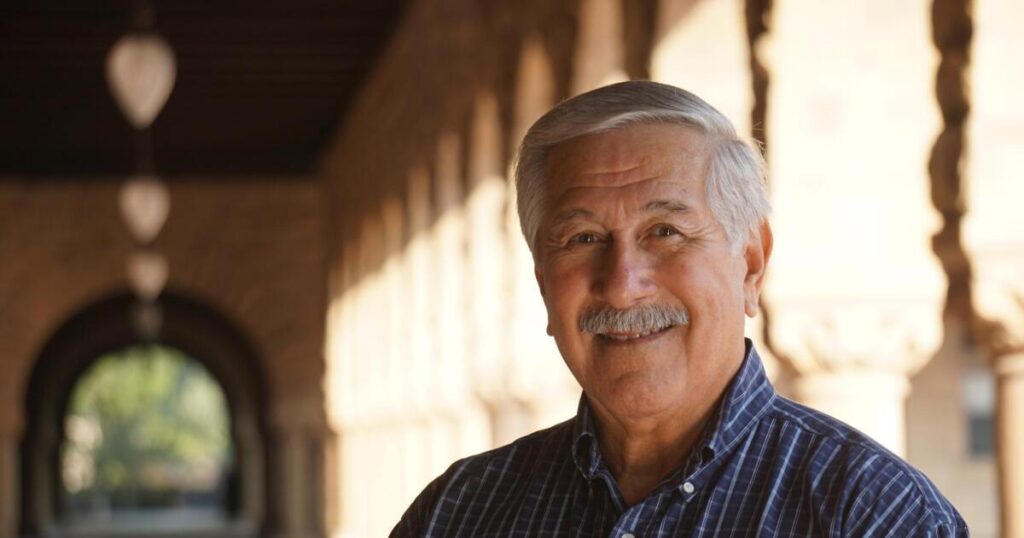

Albert M. Camarillo has been a history professor at Stanford University for more than 40 years, working to advance racial equality after experiencing it firsthand in his hometown of Compton, where he was born in 1948. His new memoir alternates between his own story and Compton’s, revealing both.

Camarillo tells the story of Compton’s growing black population and scarcity of resources in the decades after World War II, tracing his distinguished academic career as one of the founders and shapers of Chicano history, a field that was still in its infancy when he graduated in 1975 as the first Mexican American to earn a PhD in U.S. history with this specialization. As a historian, Camarillo frequently inserts episodes from Chicano and U.S. history in parallel with his own life story, which he tells in his own sobering way.

The result is a drama-free mix of memoir and historical overview aimed at a diverse audience. Throughout, Camarillo makes clear that his Chicano identity is intertwined with his academic agenda: expanding the standard narrative of U.S. history to include people like him.

Compton in Camarillo’s soul existed before the city became notorious for gang violence in the 1980s. The first part of the book traces the history of Compton from the 1910s, when his paternal and maternal families first immigrated there, to 1966, when Camarillo went to UCLA, 20 miles away. He grew up “Chicano style” – brown-skinned, poor, and dominated by what he calls “Jamie Crow.” As a young man, he witnessed Compton’s sudden transformation from a majority-white city to a majority-black city. This dramatic demographic change, like the rest of the country, quickly sparked white hostility and flight, and ultimately the evisceration of the tax base. Camarillo recounts mostly positive memories of Compton in the 1950s and 1960s, detailing the common precursors of urban decline. He attended public schools and enjoyed the company of black, white, and Latino friends. A high school teacher turned leader, Camarillo led her school’s efforts to foster multicultural understanding in the wake of the Watts Riots in 1965. The complex situation in Los Angeles after World War II prompted her to address diversity as a professor.

His K-12 education only minimally prepared him for college, and the second half of the book explains how a young man who was suspended from his freshman year at UCLA went on to become a tenured professor at one of the top universities in the country. Importantly, he discovered a love of history, coupled with a political awakening inspired by the protest politics of the time, including the anti-Vietnam War movement, the civil rights movement, and above all the Chicano movement.

Camarillo found “real freedom” in identifying himself as Chicano. By the 1960s, Chicano had emerged as a politicized ethnic identity, with activists using it to demonstrate their commitment to improving the lives of all Mexican Americans. This commitment flowed into Camarillo’s research and shaped his career. At a time when few scholars studied Mexican Americans, and those that did tended to view them as problematic, the idea that their lives and history were not only important but integral to American history was revolutionary. Even before he had finished his dissertation, he received a job offer from Stanford University.

His dissertation was published in 1979 as Chicanos in a Changing Society: From Mexican Pueblos to American Barrios in Santa Barbara and Southern California, 1848-1930, a book that remains a classic text in the field of Chicano history for its testimony to the lasting impact of the U.S. War with Mexico on the thousands of Mexicans who suddenly found themselves living in the American Southwest in 1848.

The book not only secured tenure, but also secured Camarillo’s platform to pursue racial equity in academia. Highlights of his illustrious career mentioned in the book include helping to establish the Center for Comparative Studies of Race and Ethnicity at Stanford University and fostering inter-university research across campuses. One of his most enduring legacies is that Camarillo mentored a pipeline of graduate students who in turn trained many more. Most recently, Camarillo testified before state legislators in support of California’s 2021 law that will mandate the inclusion of ethnic studies in California’s high school curriculum starting in 2026.

Though these events are far removed from Compton, the final section of the book finds Camarillo “returning to his roots,” striving to counter sensationalized reports about the city with a story of resilience and hope. Interested in the city’s history since his graduate school days, Camarillo shares some of the research he’s done since then, including oral history interviews with longtime residents. He also details how support for the city’s public education became a family issue after his eldest son became a teacher in Compton’s public schools.

The book is thus a hybrid story, and certain parts will likely appeal to different readers. His administrative and teaching successes will probably be of most interest to fellow scholars, and the information he imparts about Compton will likely appeal to Angelenos and Los Angeles history buffs. As for the young people he mentions who may one day read the story, they are the group who would benefit most from a brief historical overview that provides context for the events in his life.

Camarillo’s calm, confident, and determined demeanor permeates the book, the same demeanor that led him to join UCLA’s freshman basketball team as a walk-on and contributed to his remarkable educational journey. Neither the upheaval he and his hometown have experienced, nor the challenges he faced as a young scholar, are sources of dramatic tension. Instead, Camarillo focuses on the positive, the importance of family and community, the benefits of multiculturalism to advance research and build a more just nation, and the power of perseverance. What is striking is that while Camarillo credits his wife Susan as a constant source of support, he finds solace in the recognition that, in his words, “real social and institutional change is a multigenerational project.” In line with that sentiment, he concludes his account with the hope that the book may inspire future generations of changemakers.

There is no need to wait. Camarillo’s influential life, decades of agenda-setting scholarship, and extraordinary commitment to teaching speak to an academic career filled with kindness and generosity, even as he devoted himself to political activism. In an age of political polarization and a blithe disregard for evidence by some parties, his book offers a fresh antidote and a helpful model.

Lorena Oropesa, a professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, Berkeley, is the author, most recently, of King of the Adobe: Reyes Lopez Tijerina, Lost Prophet of the Chicano Movement.