The terrain of upstate New York, where I grew up, consists primarily of rolling hills and mountains, or what we called mountains. They had little in common with their towering cousins out West, so if you lived in one of the many small cities scattered across the region, your sight lines were very limited. I could see the streets of Albany as they extended up from the Hudson River, from the opposite shore, but that was about it. So it would be an understatement to say my sense of visual space was radically changed when I moved to Salt Lake City in 1978.

The University of Utah, where I would spend 40 years teaching photography and its history, sits in the foothills of the Wasatch Range. Now these were mountains! The western edge of the Rockies ran 160 rugged miles between central Utah and the Idaho border. But my office window faced west, where I could see the entire city, the whole valley, the lake, Antelope Island and beyond. I was sure that if I climbed to the top of one of those nearby peaks, which ascend nearly 12,000 feet above sea level, I could see the curvature of the earth.

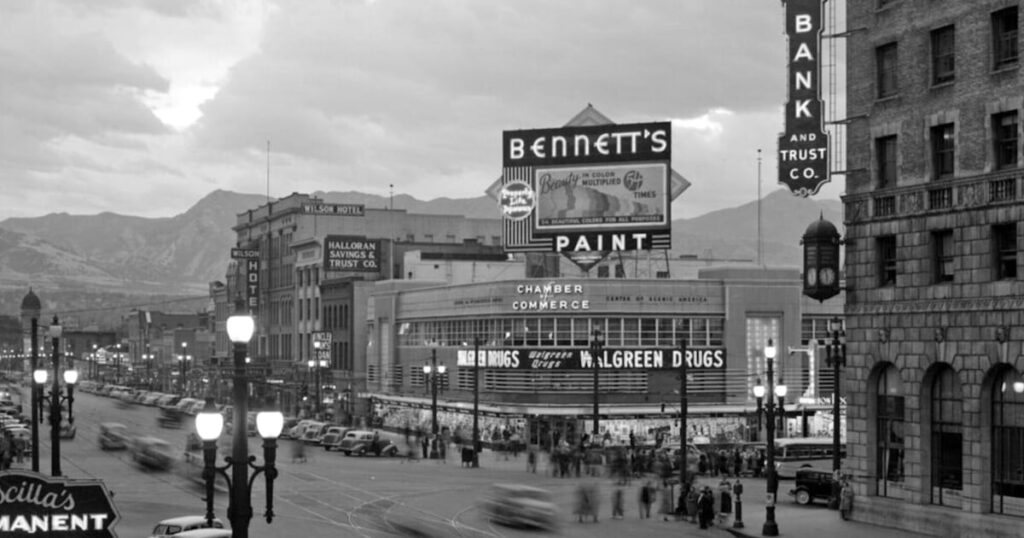

Sometimes, I would walk downtown with my camera. It had so much character, having mostly eluded the federal urban renewal projects of the 1950s and ‘60s that decimated the aesthetic and historic aspects of so many cities, including Albany. Even New York City’s Penn Station — with its lofty glass ceiling, it felt like being in a cathedral — was demolished in 1963, replaced with a subterranean train station with demoralizing low ceilings. I remember seeing images of Europe after World War II as a teenager and thinking, “We didn’t need a war to destroy our cities, we did it ourselves.”

But Salt Lake City was still relatively intact. In fact, I recognized many buildings from the work of Charles Roscoe Savage, an important 19th-century photographer known for his images of the Western landscape. He lived here for most of his life, and from 1860 to 1909, he tracked the growth of this small Western town as it became a major American city. Watching that same city grow from my office window in the foothills, I developed a deep appreciation for his work — and that of a few skilled contemporaries — which helped to create a unique photographic legacy: a visual record of a modern metropolis rising from the desert.

Salt Lake City was still a frontier settlement in 1850, when the first photographer brought his camera to town. In a way, the city and the art form would change and grow together.

I have been around long enough to know that things change, whether that means the passing of seasons (the stasis of winter to the rebirth of spring) or the evolution of cities across the centuries. These we’ve come to expect, but some changes shifted the direction of history completely, changes so definitive, there is now a before and an after. Certain inventions have that power, like the microchip (imagine life without a smartphone) or the internal combustion engine (which gets us from point A to B effortlessly, barring traffic). And then there’s photography.

Centre Theatre (1937, Salt Lake Tribune Staff) and Ken Garff Tower (2024, by the author) at 300 South and State street. | Utah State Historical Society

Centre Theatre (1937, Salt Lake Tribune Staff) and Ken Garff Tower (2024, by the author) at 300 South and State street. | Utah State Historical Society

In 1859, Oliver Wendell Holmes called the camera “the mirror with a memory.” Its advent changed everything. For millennia, we had only written and visual interpretations of what the world and the individuals who populated it looked like. The closest we came to reality was an artist’s rendering. No wonder one of the main objectives of fine art throughout that time was to depict its subjects as accurately as possible. The Dutch artists of the 1600s were masters of this kind of realism. But later, the rise of industrialization called for a faster, less expensive and more accurate method. Discovered in 1839, photography filled that need.

By 1853, this new craft was becoming more widely practiced and affordable. We know what Paris looked like that year because there are photographs to show us. London, Rome and other world capitals quickly became accessible to people who would never set foot there. In 1854, André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri introduced the carte de visite, a small, inexpensive photo card that visitors could take home to remind them of their experience. Produced by the thousands, these predecessors of the familiar postcard depicted famous places, people and everyday street life. By 1888, the Kodak camera put that power into the hands of ordinary folks who could now capture their own images, providing evidence that they were there, like a photo with the Eiffel Tower in the background. Legitimizing the experience. Providing proof.

At that time, cities like Paris, Tokyo and Buenos Aires had been around for centuries or millennia. Even New York was quite established. But Salt Lake City was still very much a frontier settlement in 1850, when the first photographer brought his camera to town. He would be followed by several notable practitioners who enjoyed the patronage of a local culture that knew they were making history and wanted it to be recorded. Together, they created a unique visual history. In a way, the city and the art form would change and grow together.

Marsena Cannon came to Salt Lake City in 1850, leaving his Boston studio to become the first commercial daguerreotypist established in the Intermountain West. Born in Rochester, New Hampshire, in 1812, he had converted to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. His focus was portraiture, with clients ranging from local residents to church leaders. He even took one of the earliest daguerreotypes of President Brigham Young. But he did also capture some views of the city. His business was successful, but another arrival would soon join him.

Savage was young, but he was no novice. Originally from Southampton, England, he had also converted to the Church of Jesus Christ before immigrating to New York City in 1856, at the age of 23. He worked in a print shop and practiced taking stereographic photos with a friend, the first such images of Long Island. It is believed that he learned from established daguerreotypists like Edward Covington. When he and later his family moved West, he started selling portraits in Florence, Nebraska, and Council Bluffs, Iowa. In the 1860s, they crossed the plains to Salt Lake City, where he took out his first ad in the Deseret News and soon partnered with Cannon.

Main street, showing the post office and the city’s first store, in 1864, by Marsena Cannon. | Utah State Historical Society

Main street, showing the post office and the city’s first store, in 1864, by Marsena Cannon. | Utah State Historical Society

This was a time of Western expansion. The federal government sent out expeditions to survey and document the land in the 1860s and 1870s, and photographers were important members of these expeditions, which would stop in Salt Lake City for supplies. In 1861, Cannon moved his family to St. George, and Savage then partnered with painter George Ottinger, who would hand-tint Savage’s photos, producing color photographs. After their partnership ended, Savage opened the Pioneer Art Gallery, taking portraits, selling views of the city and landscapes of the state, and selling equipment to photographers passing through.

When he wasn’t behind the camera, Savage was an ambitious and successful entrepreneur. Beyond portraits and documentary landscapes, he made scenic views of the growing city. He produced large single views, stereo cards and cartes de visite, many hand-tinted by Ottinger. He also worked for the Union Pacific and Rio Grande Western railroads, traveling along each line and shooting landscapes. He was one of three photographers to capture the meeting of the rails at Promontory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. He also documented the construction of the Salt Lake Temple, from the cutting of granite stone in Little Cottonwood Canyon, to the completion of the building itself — a historically significant achievement.

What makes Savage interesting is not the mere fact that he documented Salt Lake, but the way he did so. There is an emotional connection with the subject, almost an affection.

Savage was passionately interested in photography as a way of preserving history and constantly developed his own skills. When he saw Carleton Watkins’ extraordinary landscape views, he traveled to San Francisco to ask the man how he made them. He traveled to New York to catch up on technical improvements and arranged for a gallery there to carry his work for sale. He became, by the 1880s, one of the most successful and respected photographers in the country.

But what makes Savage interesting to me is not the mere fact that he documented Salt Lake, but the way he did so. It is very evident that he spent time with his subject to get the right atmosphere to visually convey something about the city. By the late 19th century, there were a number of excellent urban photographers, but only a few used light and atmosphere to capture their subject aesthetically. Charles Marville and Eugène Atget in Paris and Frederick Evans in London are good examples. There is an emotional connection with the subject, almost an affection. Savage worked in this way too.

His images are well composed, seen from the best vantage point, and made with the best technical developments of his time. His use of light and shadow gives his images a sense of specific time and place. His streets are often populated, which makes the image more intimate and helps connect the viewer to the scene. They make you want to walk down that street, look in that shop window, maybe see a friend and stop to talk for a while. In this way they become personal histories.

Over the decades, Salt Lake City changed in scope and ambition, becoming a vibrant, contemporary city by the early 20th century.

Photography changed with it. Film replaced glass plate negatives. Cameras became smaller and faster. The growth of newspapers and magazines increased the demand for images. Photojournalism became the leading form of photography from the 1920s through the 1960s, with the city as its main subject. In this manner, newspapers like the Deseret News and The Salt Lake Tribune showed people what their city looked like from different perspectives, making their own home more familiar and accessible. It was their city, their parents’ city, their grandparents’ city. These images established a link to a personal past and a common history.

It was their city, their parents’ city, their grandparents’ city. These images established a link to a personal past and a common history.

What makes a city unique? What separates this one from that other one, as a place where lives are lived and memories are made? Here, for decades, that might have meant breakfast at the Judge Café, or that dress you bought at Keith Warshaw’s or Auerbach’s or ZCMI. Or coffee at the Woolworth’s counter or Lamb’s Grill. Or a movie at the Centre Theater, with over a thousand seats and a massive 56-foot screen, demolished in 1989. Images of these places and so many others can be found in the Utah State Historical Archives, the Church History Library, the BYU archives, the Deseret News and Salt Lake Tribune archives, the Marriott Library Collection and books like “Seeing Salt Lake City: The Legacy of the Shipler Photographers,” which focuses on a later period.

Main Street and 200 south facing Southeast, captured by Charles Roscoe Savage in the 1880s. | Utah State Historical Society

Main Street and 200 south facing Southeast, captured by Charles Roscoe Savage in the 1880s. | Utah State Historical Society

At first, you might find yourself captivated by the images of buildings that no longer exist. I remember sitting in the balcony of the Utah Theater in 1988, watching Marcello Mastroianni in “Dark Eyes.” Originally called the Pantages Theater, it had 2,300 seats and a Tiffany glass ceiling! And it was there for everyone to enjoy, for the price of a movie ticket. No matter your income level, you could enter this grand historical space and connect with a shared experience. It felt like a little bit of democracy at work. After closing that same year, the theater sat ignored until 2022, when it was demolished to make room for a glass and steel high-rise apartment building that remains unconstructed. Two years on, there remains for me a gaping hole on Main Street, both literally and metaphorically.

But I’ve said this before. Cities change. And we’re fortunate to still have a wealth of historically significant buildings downtown, like the Capitol Theatre, the façade of the old Lyric Theatre, the Joseph Smith Memorial Building (formerly the Hotel Utah), the Walker Bank building, and the Rio Grande and Union Pacific train stations. There are many others. The Continental Bank building is now the Hotel Monaco, repurposed rather than torn down, which feels perhaps wiser to me than removing something special to replace it with something modern but ordinary.

In the four decades since I moved here and fell in love with this place, I’ve traveled extensively to photograph architecture and street scenes in Paris, Rome, London, Lisbon, Mexico City and New York. But I always find something interesting to photograph right here at home. Walk around downtown Salt Lake City. Spend an hour. See how it feels. Get to know it firsthand. Of course it has changed in its 176 years — sometimes for the good, sometimes not. But you can judge for yourself because we still have the photographs, a rich history of the city rising from the desert.

This story appears in the June 2024 issue of Deseret Magazine. Learn more about how to subscribe.