Chef Erling Wu Bauer grew up in Chicago to a Chinese mother and a Creole father. Chris Jung, executive chef at Wu Bauer’s new Chicago restaurant, Maxwell’s Trading, was born in Korea and grew up in New York and Washington, D.C. In creating the menu, they leaned toward eclecticism rather than pinpointing a single cuisine of the past. Maxwell’s, ranked No. 3 on America’s Best New Restaurants, offers tortellini that taste like soup dumplings and flatbreads like scallion pancakes used to scoop up hummus. Instead, the cultural medley on each plate is overtly inauthentic.

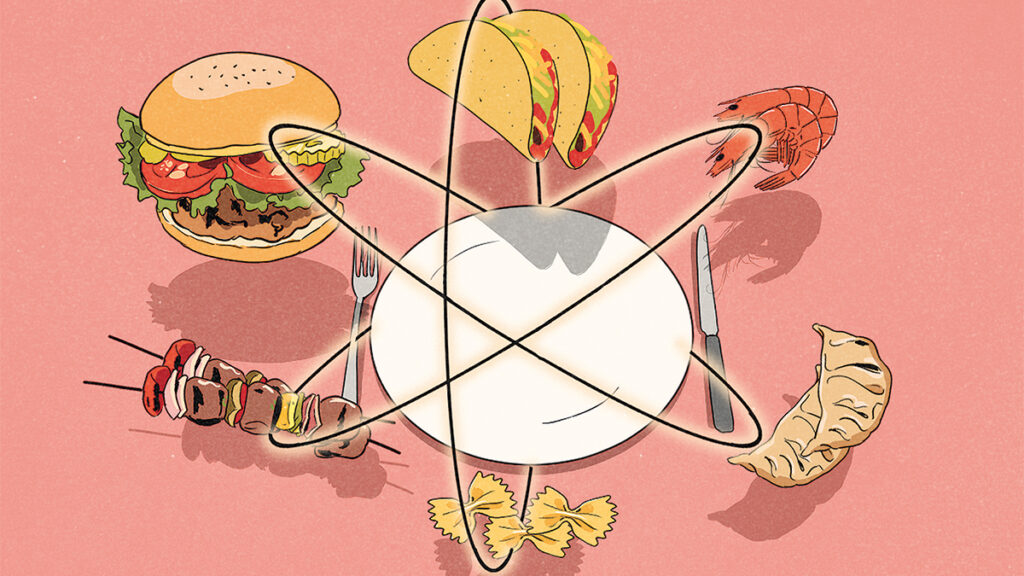

In tasting cuisines from around the country this year, it became clear that the most inventive chefs have given up on chasing notions of authenticity; some are happy to subvert it. Call it mashup, fusion, eclecticism, whatever you want to call it, chefs are no longer afraid to cross cultural boundaries in a way that has become all but unfashionable in the food world over the past 15 years.

More from Robb Report

Until recently, big-name restaurants adhered to a general ethos of authenticity, whether that came in the form of being an outgrowth of where they were based, like Noma or Fäbiken, or a restaurant striving to faithfully recreate the cuisine of a distinct culture, like Sean Brock’s explorations of Southern cooking. But the “authentic” label also carried moral weight: it signaled that the food served hadn’t been vulgarized, watered down, or thoughtlessly appropriated.

This drive for authenticity has had a valuable impact on the American culinary world: if you’ve only ever eaten at Domino’s, a pizza maker faithful to Neapolitan traditions can open your eyes to a different way of enjoying pizza, while someone whose only known Thai food is pad thai can similarly broaden their horizons with a chef faithfully recreating recipes he learned in Southeast Asia.

But as the trend continued, we began to run into limitations. For one, some restaurants became more focused on marketing than on serving authentic flavors, and customers grew tired of them. Sure, Noma sourced ingredients from nearby Scandinavia, but one of its followers claimed to do the same on a remote island in Washington state, only to be caught buying a roast chicken at Costco.

Second, there is no single truth about food. Cuisine evolves with people and places. Chefs who claim to make authenticity are likely making food that is frozen in time, and the rules that define what makes a local favorite good or bad may differ from household to household. Even neighbors can disagree, so who gets to decide what is authentic?

With that in mind, the best chefs are shedding pretense altogether. Johnny Clark named his Chicago restaurant Aneliya after his Ukrainian grandmother, but he’s willing to stray from her recipes. Chef Angie Ma of New York’s Le Bee serves a chinoise salad that’s quite different from the one made famous by Wolfgang Puck, but in any case, his salad has little to do with China. And at Nashville’s Bad Idea, Colby Lasavong is using fine-dining techniques to create the Laotian dishes he ate as a child. His scallop-stuffed crepes resemble classic Lyonnaise quenelles de brocher, but with flavors of fish sauce and a heat from Thai chili that a French chef wouldn’t think to add.

Culinary traditions are worth celebrating, of course, but so is the wave of creativity we’re currently riding on, thanks to those willing to be “inauthentic.”

Sign up for the Robb Report newsletter and follow us on Facebook , Twitter and Instagram for the latest news.

Click here to read the full article.