The fast-food industry is grappling with the devastating impact that California’s new minimum wage law for workers will have on their business.

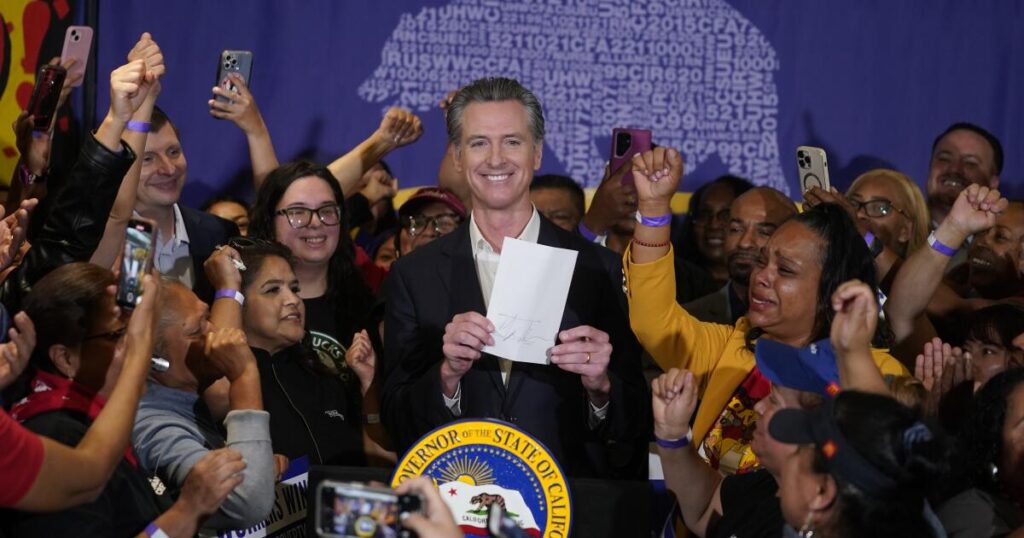

Their raw numbers certainly seem to back that up: A full-page ad in USA Today recently ran by the California Business and Industry Federation claiming that nearly 10,000 fast-food jobs have been lost in the state since Gov. Gavin Newsom signed the law in September.

The ad lists 12 chains, from Pizza Hut to Cinnabon, whose local franchisees have either cut jobs or raised prices or are considering such measures. The ad says the chains are “victims of Governor Newsom’s minimum wage,” which increased the fast-food industry minimum wage from $16 to $20 starting April 1.

Rapid job cuts, rising prices and business closures are the direct result of Governor Newsom and this shortsighted legislation.

— Tom Manzo, a business lobbyist who promotes misleading statistics

Here’s something you need to know about this claim: It’s brazen bullshit. In fact, fast food employment in California increased during the period covered by this ad, from September through January, according to surveys by the Bureau of Labor Statistics and the Federal Reserve. The claim that jobs have decreased is a clear falsification of government employment statistics.

Another thing the ad doesn’t say is that fast food industry employment has continued to grow since January. As of April, employment in the limited-service restaurant sector, which includes fast food restaurants, was up about 7,000 jobs compared to April 2023, a few months before Governor Newsom signed the minimum wage bill.

Newsletter

Latest Updates from Michael Hiltzik

Commentary on economics and other topics by a Pulitzer Prize winner.

Please enter your e-mail address

sign up

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Nevertheless, the unemployment figure and condemnation of the minimum wage law have spread rapidly in the business press and conservative media, from the Wall Street Journal to the New York Post to the website of the conservative Hoover Institution.

We’ll take a closer look at the clever tactics used by corporate lobbyists to make job gains look like job losses, but first let’s take a quick look at the overall economic situation in the fast food industry.

Few would argue that the restaurant business is easy, whether you run an upscale sit-down restaurant, a kiosk or food truck, or a franchised fast-food chain. Labor costs are one of the many expenses owners have to deal with, but they’re far from the worst in recent years. The worst of them all is food price inflation.

For example, Newport Beach-based Chipotle Mexican Grill revealed in its latest annual report that food, beverage and packaging costs were $2.9 billion last year, up from $2.6 billion in 2022, though those costs fell as a percentage of revenue to 29.5% from 30.1%. Labor costs were $2.4 billion in 2023, but as a percentage of revenue they fell to 24.7% from 25.5% in 2022.

Costa Mesa-based El Pollo Loco saw its labor and related costs fall by $3.5 million, or 2.7 percent, last year, even as they increased by $4.1 million. The company attributed the increase to previously enacted minimum wage increases and “competitive pressures” — the need to pay higher wages to attract employees in a tough labor market.

Then there’s Rubio’s Coastal Grill. On June 3, the Carlsbad chain announced it was closing 48 locations, about a third of its 134 locations in California. As my colleague Don Lee reported, Rubio’s cited rising costs of doing business in California as the reason for the closures.

But that’s not the whole story. The biggest expense Rubio’s faces is its debt, a burden that has grown since it was acquired by private equity firm Mill Road Capital in 2010. By 2020, the chain had $72.3 million in debt and filed for bankruptcy. In fact, in a full bankruptcy court filing on June 5, the company acknowledged that it was facing an “unsustainable debt burden” along with minimum wage increases.

The company emerged from bankruptcy at the end of 2020 with a settlement that included a reduced debt burden. Then the pandemic became a major headwind. It once again struggled with debt, owing $72.9 million to its largest creditor, TREW Capital Management, a firm that specializes in lending to distressed restaurant businesses. On June 5, two days after announcing the store closures, the company filed for bankruptcy again. The case is pending.

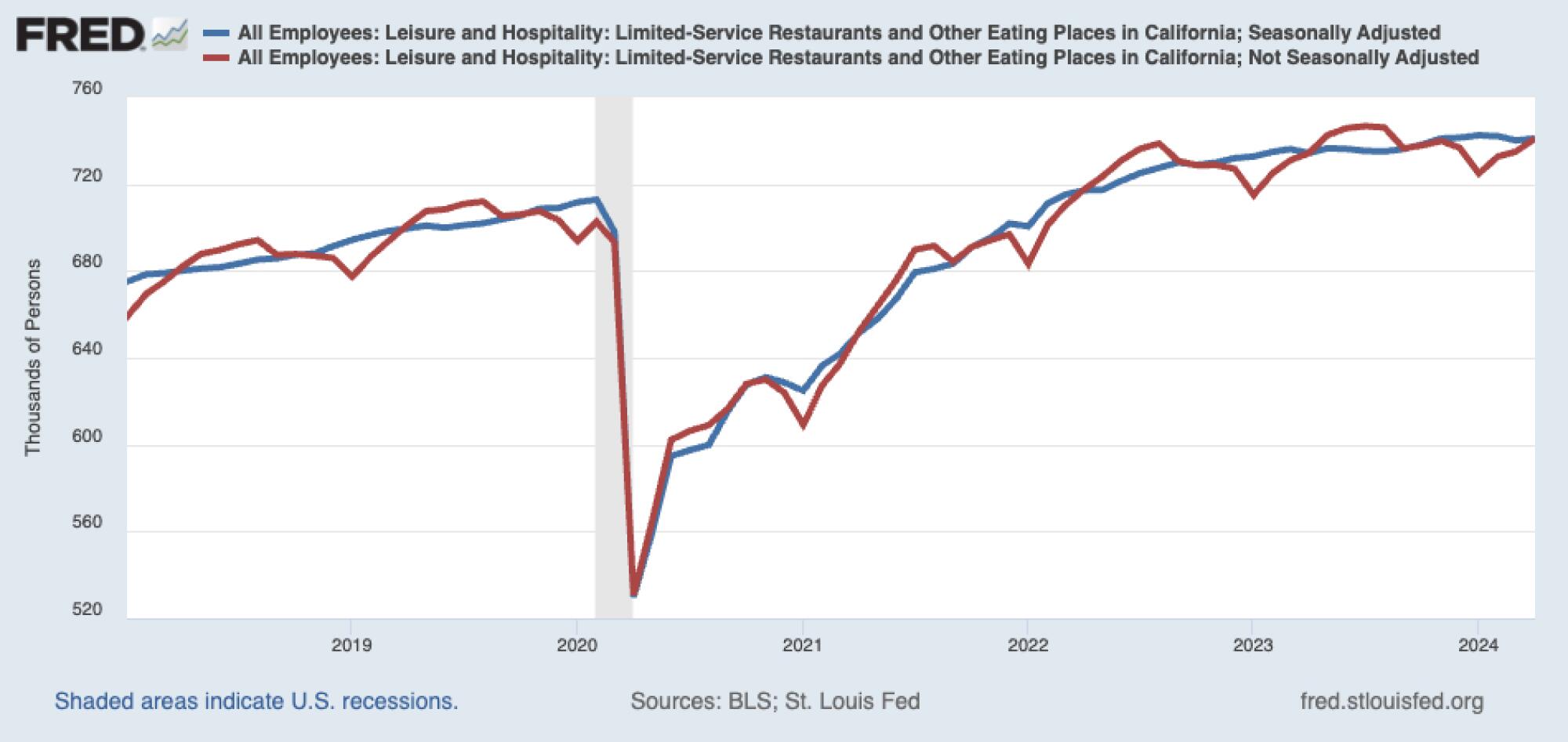

Fast food and other restaurant employment declines annually from fall to January due to seasonal factors (red line). Seasonally adjusted (blue line) gives a more accurate picture of employment trends. The sharpest decline in 2020 was caused by the pandemic.

(Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis)

It’s important to note that private-equity acquisitions often involve large amounts of debt, which gives the acquirer a way to extract cash from the company, even if it complicates the company’s path to profitability. It’s unclear whether that’s a factor in Rubio’s latest woes.

That brings us back to the argument that California’s fast food job losses are due to new minimum wage laws.

The allegations were made in a report by The Wall Street Journal on March 25, which reported that restaurants across California were cutting staff in anticipation of a minimum wage increase that takes effect on April 1.

According to the article, employment at fast food restaurants and “other limited service restaurants” in California was 726,600 in January, down 1.3% from September of last year when Governor Newsom signed the minimum wage law. This brings employment in September to 736,170, representing a loss of 9,570 jobs from September to January.

The Wall Street Journal figures were used by UCLA economics professor Lee E. Ohanian in an article published April 24 on the website of the Hoover Institution, where he is a senior fellow.

Ohanian said the pace of fast-food job losses is much faster than the overall decline in private employment in California from September through January, saying, “This makes it tempting to conclude that many of the fast-food job losses are due to the higher labor costs that employers will have to pay when the new law goes into effect.”

In a USA Today ad, CABIA cited Ohanian’s article as support for its claim that minimum wage legislation has led to the loss of “approximately 10,000” jobs in the fast-food industry. “Rapid job cuts, rising prices and business closures are the direct result of Governor Newsom and this shortsighted legislation,” CABIA founder and chairman Tom Manzo said on the organization’s website.

The problem with this number is that it is derived from government statistics that are not seasonally adjusted. Seasonal adjustment is very important when tracking employment in seasonal industries like restaurants, because restaurant business and employment fluctuate in predictable patterns throughout the year. For this reason, economists largely prefer seasonally adjusted numbers when plotting employment trend lines for these industries.

The WSJ figures are consistent with unadjusted figures for California fast-food employment from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. (Thanks to financial blogger extraordinaire Barry Ritholtz and his colleague Anonymous at Invictus for bringing this issue to the spotlight.)

On a seasonally adjusted basis, employment actually increased by 6,335 from September to January, from 736,160 to 742,495, according to California fast-food restaurant figures from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis.

That’s not to say that some fast-food chains and hospitality companies haven’t cut jobs this year, and for those who have been laid off, employers’ manipulation of the statistics doesn’t ease the pain of losing their jobs.

Still, as Ritholtz and Invictus point out, textbook economics tells us that the proper way to deal with seasonally adjusted numbers is to use year-over-year comparisons that ignore seasonal trends.

Doing so for California’s fast food statistics paints a different picture than the one CABIA paints: In the industry, employment in September rose from a seasonally adjusted 730,000 for 2022 to 741,079 for 2024. In January, employment rose from 732,738 for 2023 to 742,495 this year.

Restaurant industry lobbyists cannot pretend they are unaware of the concept of seasonality: it’s a well-known feature of the restaurant industry and has long been one of its defining characteristics.

Restaurant consultancy Toast also offers restaurateurs tips on how to manage the phenomenon, noting that “April to September is the busiest time of the year,” mainly because that period includes Mother’s Day and Father’s Day, “the two busiest days of the year for restaurants,” and also because good weather encourages customers to dine out more.

When is your slowest season? November through January, “when a lot of people travel for holidays like Thanksgiving and Christmas and spend time cooking and eating with their families.”

In other words, lobbyists, the Journal and their advocates all voiced their concerns based on a known pattern of restaurant employment peaking annually in September and then declining through January.

They blame this trend on California’s minimum wage law, which clearly has nothing to do with it. I can’t see into their minds, but given the circumstances, their argument seems a bit cynical.

Heather Haddon, the author of the Wall Street Journal article, did not respond to my questions about why she appeared to use non-seasonally adjusted figures when seasonally adjusted figures would be more appropriate. Tom Manzo, founder and president of CABIA, also did not respond to my request for comment.

“If the data is not seasonally adjusted, then conclusions about AB 1228 cannot be drawn from it,” Ohanian acknowledged in an email. He interpreted the Wall Street Journal’s numbers as seasonally adjusted and said he plans to write an article on the issue later this summer and will contact the Journal about the matter.

He very rightly noted that the increase in labor costs due to the law is significant, and that “if franchisees continue to face significant increases in food costs later this year, the industry will be in a tough spot.” Fast food companies have already implemented significant price increases to offset the increased costs, he noted. “So the question is, how sensitive are fast food consumers to price increases?” he said, adding that he plans to continue researching the topic this year.