![]()

By Alden Gonzalez, ESPN Staff Writer June 12, 2024, 8:23am ET

CloseESPN baseball reporter. Covered the LA Rams for ESPN from 2016-2018 and the LA Angels for MLB.com from 2012-2016.

It was at the San Diego Padres’ Biomechanics Laboratory in Point Loma last December that Jeremiah Estrada went from bit part major leaguer to one of the most effective relief pitchers in baseball.

That was just weeks after the Chicago Cubs removed him from their 40-man roster and months before his arm was due to be in good shape for the 2024 season. Estrada’s new pitching coach, Ruben Niebla, wanted to watch him pitch in hopes of finding a pitch that might complement his dynamic but worn-out four-seam fastball.

He tried cutters, curves, changeups, sliders, and constantly changed grips on most of them. Then Estrada unveiled the split changeup that would change the trajectory of his career. He invented it out of desperation, and now bashfully calls it the “chitter.” He held the ball between his middle and ring fingers in a modified “Vulcan” grip, and Niebla didn’t think he had much control over it. But he threw it. The ball was in the mid-80s, dipped badly, and ran toward his arm. The first comment came from the catcher.

“Oh my goodness.”

Editor’s Pick

2 Related

Then Estrada threw another one.

“I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is bad,'” Niebla said. “I looked at the numbers, I looked at the features, and I thought, ‘Actually, this isn’t bad. Let’s try it again.'”

A bullpen session scheduled for 15 pitches stretched to about 70. By the end, Niebla was convinced the 25-year-old Estrada had found the second pitch type he had been searching for throughout his career.

“He said, ‘All right, your splitter is your shitty pitch,'” Estrada recalled. “I felt good because I’d worked so hard on that pitch. That pitch went well.”

Estrada pitched just 40 professional innings in the four years since being drafted out of high school in Palm Desert, California, in 2017. A persistent forearm injury led to Tommy John surgery, then a deadly COVID-19 infection that left him 30 pounds lighter and nearly killed him. His next two seasons with the Cubs were mediocre, highlighting Estrada’s frustration in searching for a way to add spin to his pitches.

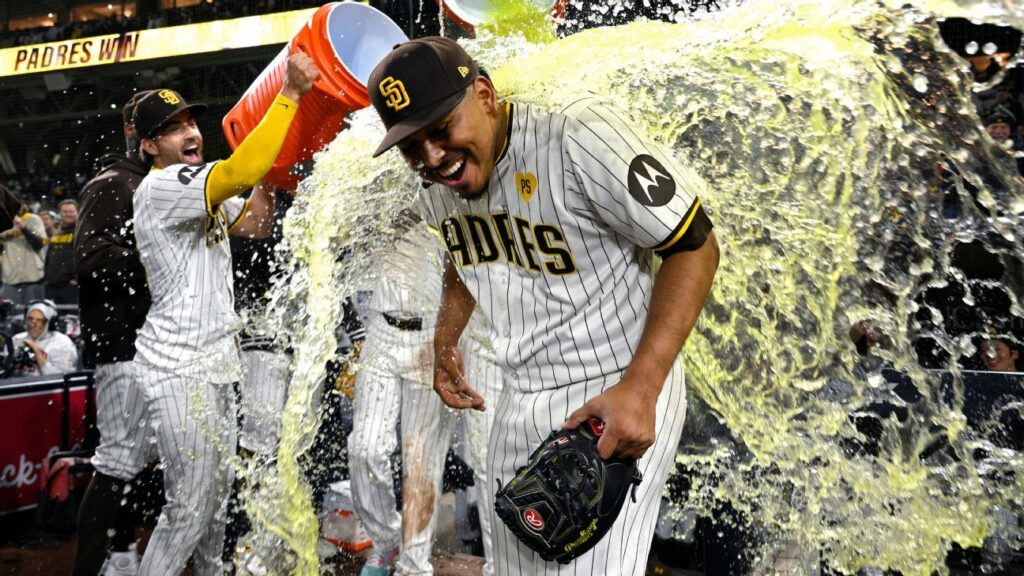

Now he has emerged as one of this season’s most unexpected success stories, striking out 13 consecutive batters last month to set an expansion-era record and post an 0.86 ERA. He has anchored the back end of the Padres’ relief corps, focusing on a three-pitch combination that confounds hitters: his ever-present fastball, a Padres-modified slider and a split-change that Estrada practically invented.

“I’ve worked so hard for this,” Estrada said, “I’ve overcome so much to get to this point, to be here, but I still feel like I’m fighting.”

One day in August 2021, Estrada woke up on the floor of a hotel room in Myrtle Beach, South Carolina, with paramedics around her. She didn’t know how she got there, but she did know that she couldn’t breathe.

What started out as mild COVID-19 symptoms — he lost his sense of taste and smell but felt nothing but drowsiness — quickly became more severe. A few days earlier, Estrada had vomited so frequently over the course of 24 hours that he’d set up a bed in his bathroom so he wasn’t far from the toilet. When he was admitted to the hospital later that day, he said he was “so dehydrated that my hands were like dinosaurs.”

He was released from the hospital that same day, but when he returned home, he continued to be short of breath and his vision was so blurred he couldn’t see the screen of his iPhone. He used Siri to contact his father in California and tell him to call an ambulance. When paramedics arrived, his oxygen saturation had dropped to 70%. When he returned to the hospital, his outlook was even bleaker.

“They called my father and said, ‘The situation is not good,'” Estrada recalled. “They said, ‘Your son only has one day left to live.'”

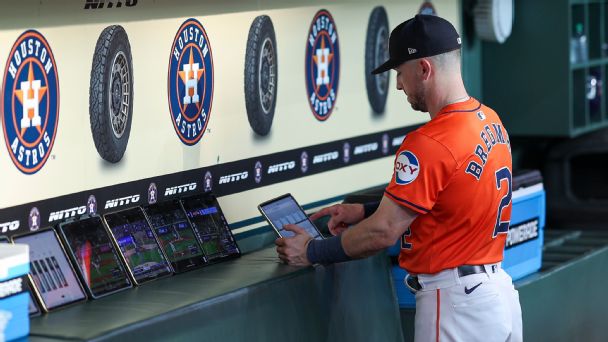

Load management is MLB’s next big thing

Front offices are evaluating players’ on-field performance in ways they’ve never done before, so let’s take a look at how this impacts baseball.

Jesse Rogers »

Estrada, who has not been vaccinated, doesn’t remember how long he was in the hospital last time. All he remembers is that he woke up one morning with a cold nose, which doctors took as a sign he might be able to breathe on his own again. Suddenly, he could only eat brown sugar graham crackers and nothing else. He started getting up. Eventually, he was allowed to go home, by which point his weight had dropped from 215 pounds to 172.

Estrada’s sense of smell returned within six weeks, but he lost his sense of taste for an entire year. His short-term and long-term memory was severely impaired, and he was unable to recall his experiences for several weeks afterward. His brain was so foggy that he was unable to sleep more than three hours at a time. He spent the better part of two months confined to his room, afraid to even go outside. Doctors initially diagnosed him with illnesses including myocarditis and pneumonia, Estrada said.

It wasn’t until the start of spring training in 2022 that he began to get back to his old self. “The only step I missed with COVID-19 was dying,” Estrada said. “That was it. That was all I had left.”

When the 2022 season began, Estrada was 23 and pitching in Class A. He’d spent his first full season in 2018 rehabbing a sprained ulnar collateral ligament and most of 2019 recovering from Tommy John surgery. The pandemic canceled the entire 2020 minor league season, and Estrada’s battle with COVID-19 marred the end of 2021. The first day of spring training in 2022 consisted of just a 10-minute jog. And it was enough.

“I’m not gonna lie, my whole body hurt,” Estrada said. “I couldn’t move the next day.”

Still, Estrada moved up three minor league levels that summer and was promoted to the big leagues late in the season. He entered 2023 on the fringe of the Cubs’ major league roster but still far from fully formed. The team viewed him as a fastball-and-slider pitcher, Estrada said, and discouraged him from throwing the changeup and curveball he’s more familiar with. He became overly reliant on his fastball, which became too predictable.

Estrada still remembers the game on May 23, 2023. Estrada reached base in the bottom of the sixth inning with the bases loaded and no outs. New York Mets first baseman Pete Alonso reached base on a fielder’s choice and began yelling at the next batter, Daniel Vogelbach, “Fastball! Fastball! Fastball!” Vogelbach only saw the fastball and hit the third pitch onto the warning track for a sacrifice fly.

Prize Watch

Will Betts beat Ohtani? Will Soto beat Judge? Get the latest on the MVP, Cy Young Award races and more.

![]() Bradford Doolittle »

Bradford Doolittle »

Soon after, the Cubs tried to teach Estrada a splitter similar to the one thrown by veteran relief pitcher Mark Leiter Jr. But Estrada couldn’t get a grip on the pitch; it just didn’t fit between his index and middle fingers. He threw a bunch of bullpen pitches trying to figure it out, then played in a late afternoon game. His fastball velocity dropped. The feel of his slider disappeared. An attempt to throw a sweeper never materialized. But he kept searching.

“I don’t give up,” Estrada said. “If I don’t understand something, I want to figure something out. I didn’t know how to tell them, ‘I don’t want to do this.’ I didn’t want to upset them because I knew they were doing the best they could for me. But at a certain point I got fed up. I was frustrated.”

Estrada appeared in 13 Triple-A games from June 16 to August 3, posting an 11.77 ERA. At that point, he had thrown 33 innings in Triple-A and the major leagues combined, walking 36. Rather than accept a demotion to Double-A, Estrada convinced the Cubs to send him to their pitching facility in Mesa, Arizona, where he hoped to get as many bullpen ins as possible under the direction of pitching coordinator Tony Koogle and figure something out.

For nearly a month, the two tried out cutters and gyros and pored over video of Stephen Strasburg and Eric Gagne throwing changeups. They eventually settled on a “Vulcan” grip similar to Gagne’s, in which the ball is held between his middle and ring fingers. After some trial and error, Estrada figured out how to get the ball to feel right: Place your ring finger on the seam, curl your middle and index fingers to the side of the ball, and tell yourself to throw it the same way you would a fastball.

“I threw it once and it worked,” Estrada said. “It was like a light bulb went on.”

During a recent appearance on MLB Network, Estrada talked about the “chitter” grip, which prompted kids around the world to post videos to his social media feeds of themselves trying to imitate it. For Estrada, it took months to perfect the technique. Soon after discovering the pitch, Estrada began carrying a baseball everywhere he went, holding it that way whenever his right hand was free: in bed before falling asleep, in the bathroom while brushing his teeth, in the driver’s seat of his car when the light turned on or while waiting for his order to be served at a restaurant.

Estrada, who returned to Triple-A late in the 2023 season, threw the pitch only a few times — not enough for the Cubs to gauge its impact. They removed him from the 40-man roster on Nov. 1, the night of his 25th birthday. Five days later, the Padres, intrigued by the characteristics of his fastball, claimed him on waivers. About a month later, during a long bullpen session with Niebla, Estrada found what he’d been waiting for: a connection.

World Series Teams

How far is your favorite team from winning?

![]() Bradford Doolittle »

Bradford Doolittle »

“We were having fun,” Estrada said, “and that’s when I knew we had a real relationship. We hit it off.”

Estrada pitched a shutout in spring training with the Padres and was named to the active roster from Korea for the season-opening series. The Padres recalled him near the end of April and he pitched well, allowing just two runs in 19 2/3 innings while striking out 33 and walking five.

He struck out five Cincinnati Reds batters he faced on May 23, all five New York Yankees batters he faced on May 26 and all three Miami Marlins batters he faced on May 28, the longest consecutive strikeout streaks since at least 1961. All of them came on strikeouts. Opponents have gone 4-for-25 with 13 strikeouts against his split-change pitch, but have also struggled against his fastball (5-for-37 with 15 strikeouts) and his new slider (1-for-11 with 6 strikeouts).

The Padres had been struggling for the first month of the season with how to fill the gap left by star closer Robert Suarez, and Estrada’s emergence has alleviated those concerns.

He learned something on his journey there.

“What everybody, every athlete, needs to know is, ‘While you’re here, you can either be who you are or be who people expect you to be,'” Estrada said. “But only you know yourself. Only you know how your body feels. Only you know how you feel about yourself. When they told me about the splitter with the Cubs, I wasn’t sure. I was like, ‘I don’t want this, but I’m going to do it because you guys are the boss.'”

“But then Ruben said, ‘Yes, that’s what you said,’ and that gave me confidence. That was everything.”