A failed looting attempt led archaeologists to an Underground Age complex in Turkey that may have been used by fertility cults in the first millennium BC, according to a new study.

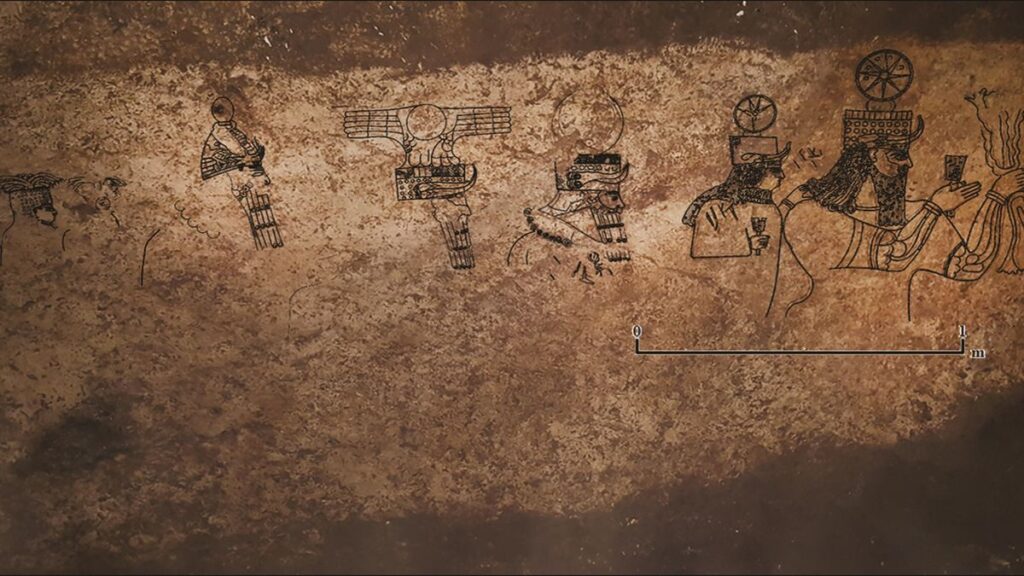

The walls of the ancient site, which has yet to be fully explored due to structural instability, contain rare rock art depicting a procession of gods painted in the Assyrian style. The art style appears to have been adopted by local groups, showing how strongly the culture of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, which began in Mesopotamia and later expanded into Anatolia, was infiltrated by the peoples it conquered in the region, says a new study published online May 11 in the journal Antiquity.

“This discovery attests to the Assyrian hegemony in the region at an early stage,” Selim Feru Adari, an associate professor of ancient history at Ankara University of Social Sciences and one of the study’s authors, told LiveScience in an email. “The wall panels contain depictions of a procession of gods that contain previously unknown elements, and Aramaic inscriptions describing some of the gods combine iconography from Neo-Assyrian, Aramaic and Syro-Anatolian pantheons.”

Authorities learned of the ancient underground facility’s existence in 2017, when looters who discovered it beneath a home in a Turkish village decided to target its treasures. But police thwarted the raiders, and investigators soon discovered an artificial opening the looters had cut into the floor of a two-story house in the village of Bashvuk in southern Turkey. Police notified the Şanlıurfa Archaeological Museum after the discovery, and archaeologists there determined that the roughly 7-by-5-foot (2.2-by-1.5-meter) opening led to an entrance chamber carved into the limestone bedrock inside the underground facility.

Related: Roman gladiatorial stadium unearthed in Türkiye

The underground complex dates from the Early Neo-Assyrian period (c. 9th century BC) and includes upper and lower galleries and an entrance chamber, the original opening of which has yet to be discovered.

Adali said museum experts carried out rescue excavations in August and September 2018. But they were halted after two months due to the instability of the site. The area is now under the legal protection of Turkey’s Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

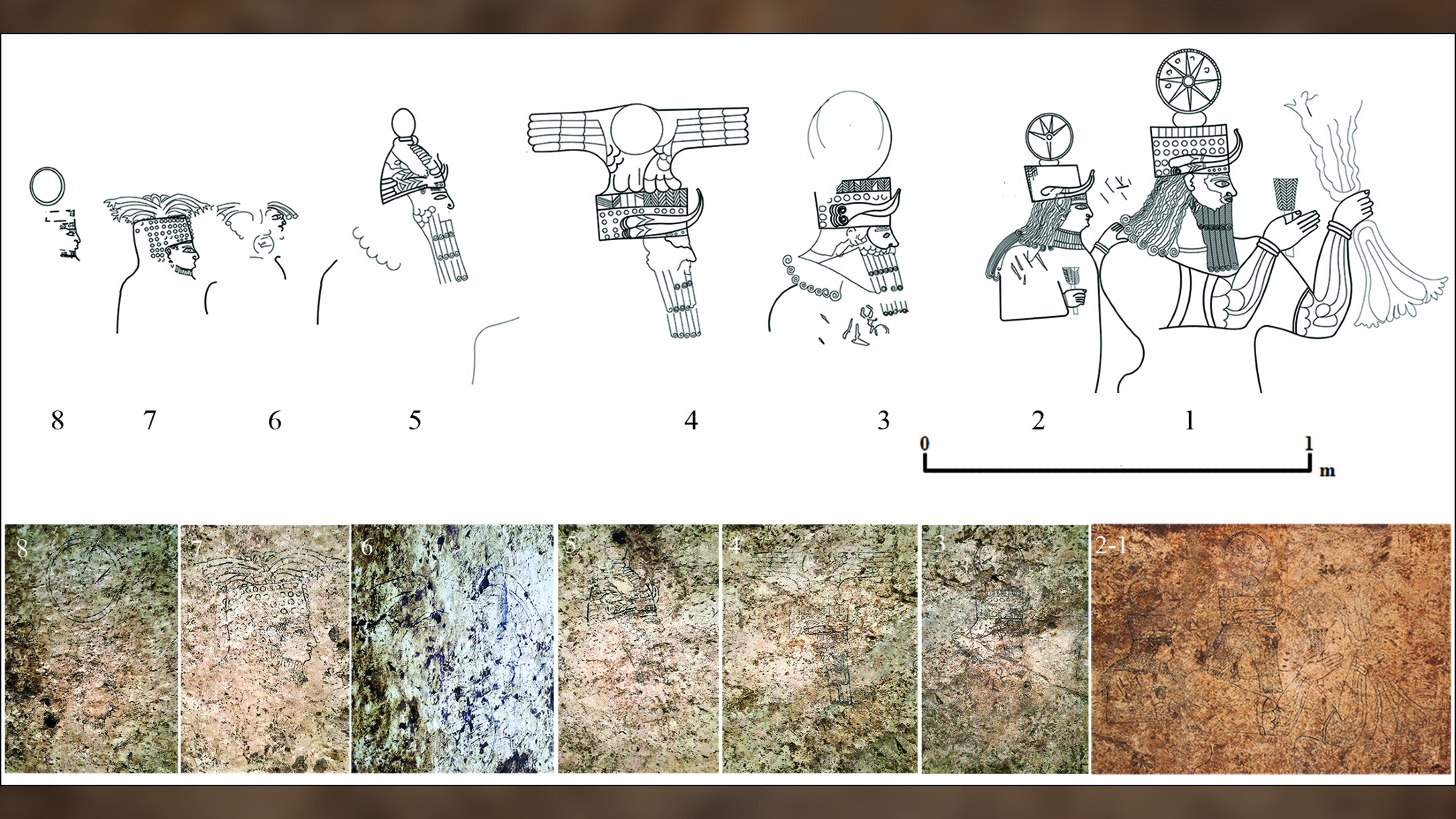

Annotative sketch of the Basbyuk pantheon (top) and a photograph of the scene (bottom). (Images courtesy of: Photography by Y. Koyuncu, M. Onal, Annotative illustrations by M. Onal, Laser scan by Cevher Mimallik, Antiquity Publications Ltd)

During the brief excavation, archaeologists removed eroded sediment from the underground chamber and discovered decorative rock reliefs carved into wall panels depicting processions of Aramaic deities, some of which are accompanied by Aramaic inscriptions.

The excavators sent photos of the panel’s inscription to Adari, who discovered that the panel was of great historical significance.

Image 1 of 4

Photograph of an underground complex in southern Turkey. (Image courtesy of C. Uludağ; Antiquity Publications Ltd)

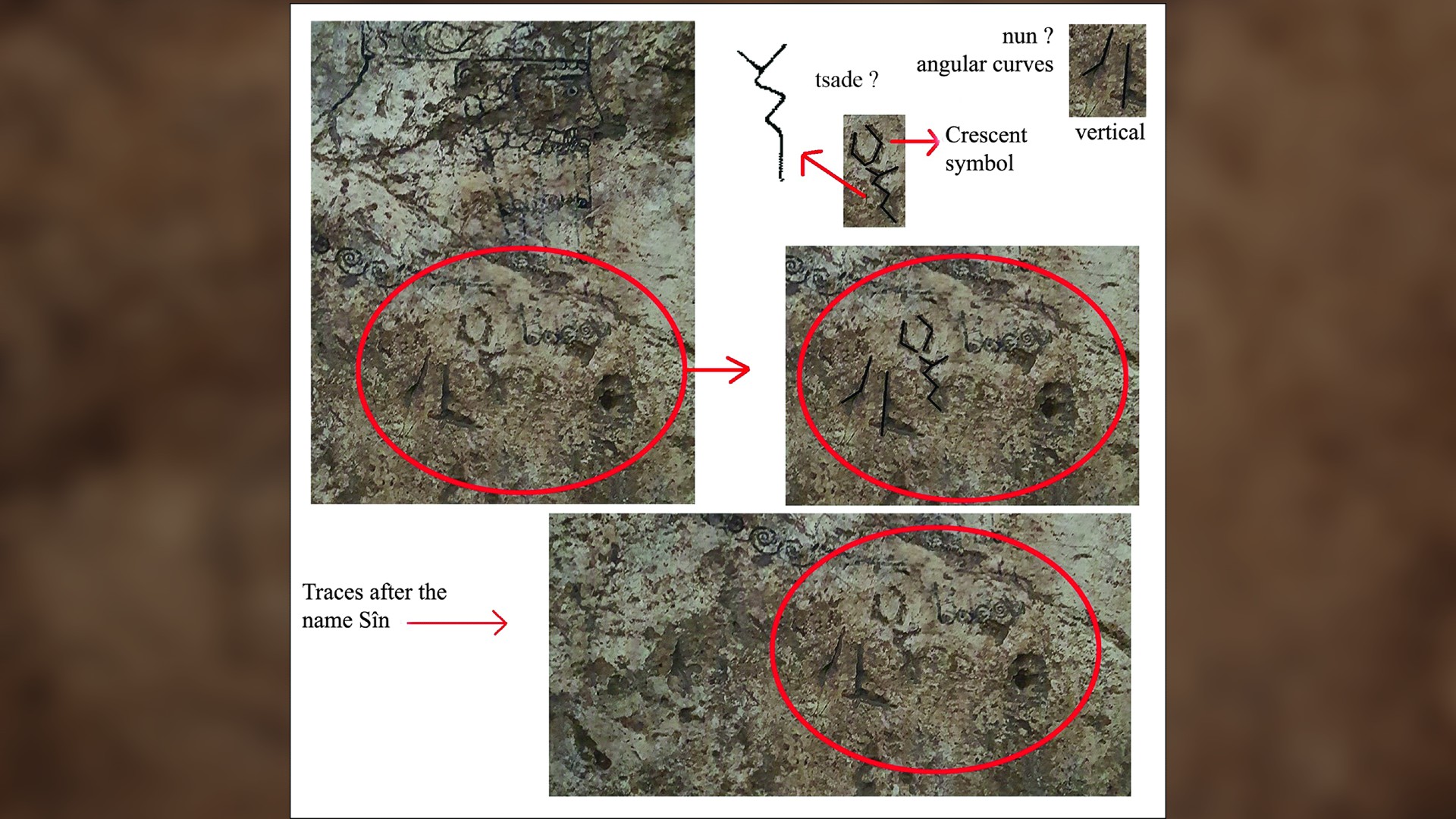

Photograph of an underground complex in southern Turkey. (Image courtesy of C. Uludağ; Antiquity Publications Ltd) A short Aramaic text on the moon god Sin (Image courtesy of SF Adalı, created by Antiquity Publications Ltd)

A short Aramaic text on the moon god Sin (Image courtesy of SF Adalı, created by Antiquity Publications Ltd) Part of a panel depicting Hadad, god of storms, rain and thunder, and Atargatis, the chief Syrian goddess. (Image courtesy of Önal, M. et al; Antiquity Publications Ltd)

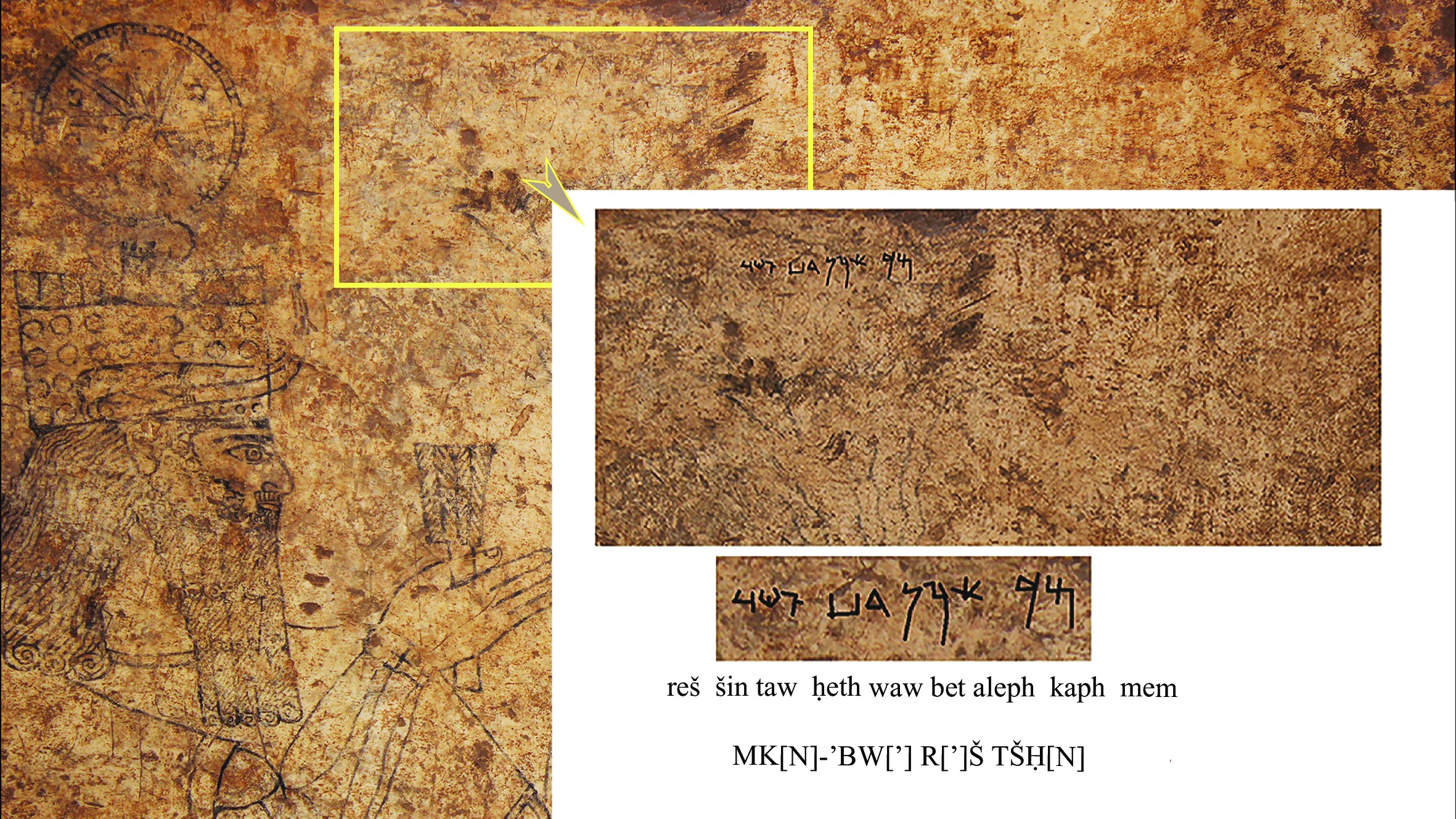

Part of a panel depicting Hadad, god of storms, rain and thunder, and Atargatis, the chief Syrian goddess. (Image courtesy of Önal, M. et al; Antiquity Publications Ltd) Archaeologists discovered Aramaic writing to the right of the Storm God’s head. (Image credit: SF Adalı, created by Antiquity Publications Ltd)

Archaeologists discovered Aramaic writing to the right of the Storm God’s head. (Image credit: SF Adalı, created by Antiquity Publications Ltd)

The expansion of the Neo-Assyrian Empire into present-day Turkey sparked a cultural revolution in which the Assyrian elite used courtly art to express their power over the local Luvian and Aramaic-speaking population.

The researchers found that Bashbyk’s wall panels show how Assyrian art was incorporated into Aramaic styles in local towns and villages.

The study said it was not possible to identify four of the eight gods depicted on the panel. The Aramaic inscription names three gods: Hadad, the god of storms, rain and thunder; his consort Atargatis, the goddess of fertility and protection; Sin, the moon god; and Shamash, the sun god. The image of Atargatis is the oldest known depiction of the Syrian chief goddess from the region, the researchers added.

“The inclusion of Syrian-Anatolian religious themes indicates the incorporation of Neo-Assyrian elements in a way that was not expected from previous finds,” Adari said in a statement. “They reflect an earlier phase of Assyrian presence in the region, when regional elements were more emphasized.”

The deities on the wall panels suggest that it was “a center of a regional fertility cult with Syro-Anatolian and Aramaic deities, and the rituals were overseen by early Neo-Assyrian authorities,” Adari told LiveScience. One of those officials may have been Mukin Abu’a, a Neo-Assyrian official who lived during the reign of Assyrian king Adad-nirari III (811-783 B.C.). The researchers identified inscriptions that appear to refer to Mukin Abu’a. Mukin Abu’a may have controlled the region and used the complex to blend with locals and win them over, the researchers said.

On the other hand, the presence of Neo-Assyrian art at the complex doesn’t necessarily mean that imperial artists produced the panels. Rather, Adari said, it’s more likely that “the panels were produced by local artists in the service of Assyrian authorities, who adapted Neo-Assyrian art to the local context.”

He added that only a small portion of the entire site has been explored so far, so the team believes that further excavations could uncover more of the underground facilities and potentially more artworks. Full excavations will begin once the entire site has been cleared, in accordance with Turkey’s Cultural Heritage Law.

Originally published in Live Science.