“A Deeper South” combines history, travelogue, memoir and social commentary, and while it veers into so many editorial lines, it keeps coming back to Candler’s central theme of how the insidious “Lost Cause” mythology has dotted our landscape with so many Confederate monuments.

The author is Candler Candler, whose family tree includes founders of Coca-Cola and Emory University, as well as Georgia senators, governors, judges, and militia leaders, many of whom did not live on what the author considers to be the right side of history.

Candler, who grew up as a “privileged white male” in Atlanta, discovered the complicated history of his ancestors and his hometown during college. He went on to become a theology professor at Baylor University, but felt he had become “a fragment of myself” as an academic, so he left his tenured position to create works like “A Deeper South.”

During his college years in the late ’90s, Candler would drive the backroads of the South with friends, reveling in the quirkiness and quirkiness of these remote places. A few years ago, he retraced many of those earlier journeys, hitting Georgia, Tennessee, South Carolina, Florida, Alabama and Mississippi, taking photos and notes along the way.

During his travels, Candler was struck by the gap between the roughly 2,000 Confederate monuments across the South and the absence of memorials to the thousands of Black people lynched between the late 1800s and the late 1960s.

Candler explains that after the Civil War ended, there were few Confederate monuments. Then, between 1900 and 1920, when white supremacy once again sealed off the area, memorials sprang up everywhere, often near the courthouse. The memorials’ true purpose, Candler writes, wasn’t to honor the dead, but to claim the area as “white space.”

No bar was too low for the Daughters of the Confederacy’s desire to rewrite history. Henry Wiltz, commandant of the Andersonville prison camp in South Georgia, was one of the few men to be tried and executed for war crimes. But the organization erected a large obelisk in Wiltz’s honor in the center of Andersonville, “to save the name of Wiltz from the taint it has received from deep-rooted prejudice,” the plaque reads.

It’s not just Confederate statues that anger Candler: A life-size statue honoring James Brown in his adopted hometown of Augusta “bears no trace of James’s fierce masculinity or the sexual, racial, and political anguish he projected” and seems like “an attempt to diminish him,” reluctantly erected by “a city long uneasy about him.”

In a brief but scathing art critique, he describes Brown’s statue as “a black Josh Groban in a cape.”

Candler traveled extensively across six states, hitting the usual spots: Tuskegee, Alabama, home of the HBCU founded by Booker T. Washington; the crossroads in Mississippi where blue legend Robert Johnson claimed to have sold his soul to the devil; Charleston, South Carolina; and Memphis. And he also visited unusual places like the Big Chicken in Marietta, built in 1963 not to advertise KFC but for Johnny Reb’s Chick Chuck and Shake fast food restaurant. All rooted in those four years.

He delves at length into the impenetrable mysteries of the Okefenokee Swamp, always scholarly, name-dropping Homer, Virgil, Dante, and cartoonist Walt (“Pogo”) Kelly, and writing about the failed 19th-century attempts to clear and drain the swamp to provide valuable land. The reclamation schemes relied heavily on prison labor (aka slavery). Fortunately, the swamp prevailed and is now a U.S. National Wildlife Refuge, but titanium mining companies are once again trying to monetize this unique natural phenomenon.

Candler’s observations are sharp: At the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, where the names of 4,000 lynching victims are inscribed on hanging steel boxes resembling coffins, “the steel weathers and oxidizes, tarnishing like rust. … Often the tarnish runs down the steel’s surface like bloodstains.”

Candler dwells a little on his family history, which is understandable, but it only makes the book longer rather than better.

The appeal of “A Deeper South” lies in how much even a student of history can learn about important details of our region’s past. And as a student, don’t be fooled by one of his great quotes: “The only thing that never goes away, no matter how much you ignore it, is your own ignorance.”

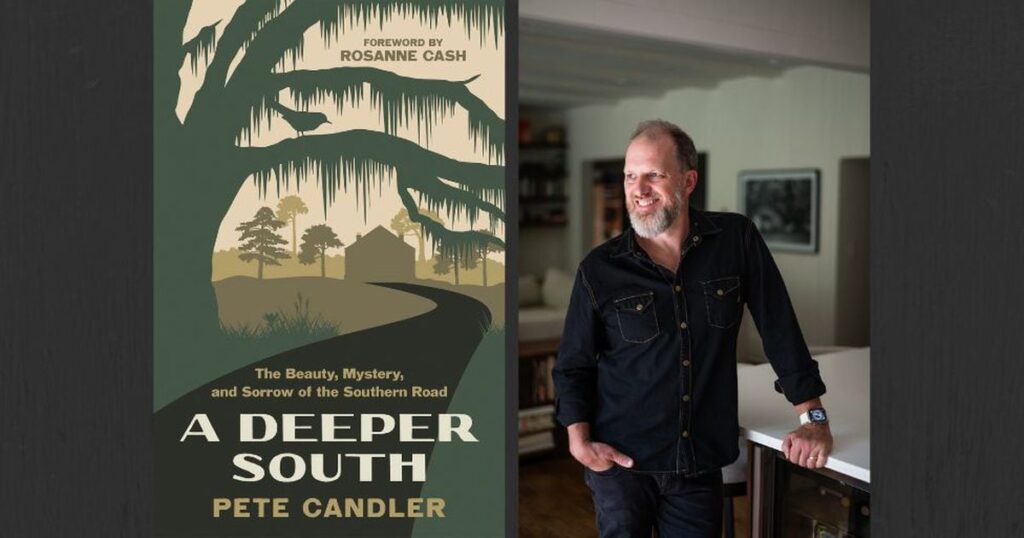

“Deeper South: Beauty, Mystery, and Sorrow of the Southern Road”

Pete Candler

University of South Carolina Press, 400 pages, $27.99