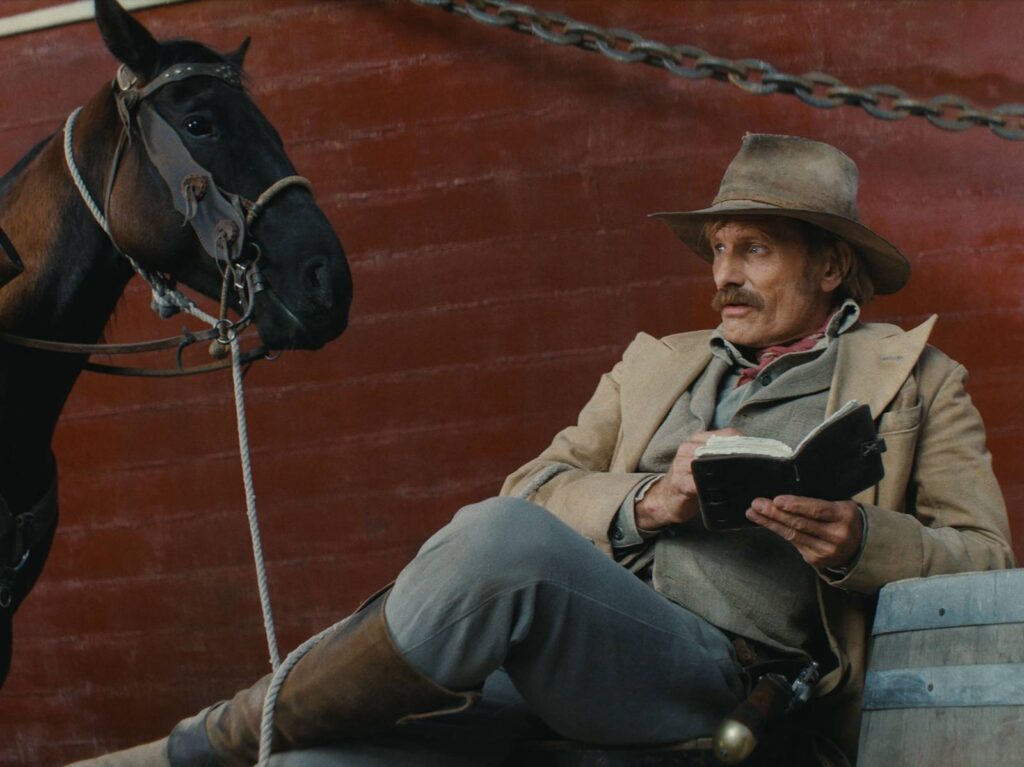

Luxembourg City sits in the heart of Western Europe, high in the valley of the Alzette River. It’s a rubbish-free Eurotopia, where trams are free and the streets are among the safest in the world. It’s a far cry from the frontier justice of The Dead Don’t Heart, a revisionist Western about love in a lawless place. The film was written, directed and starred Viggo Mortensen, who, never one to slack off, also composed the film’s score. “I also composed the score for my first film,” the affable, polite polymath, casually dressed in a checked shirt, explained to me on a recent morning at the Lux Film Festival. “That film took a long time to get funded, longer than this one, and while I was waiting I was thinking, ‘What can I do?’ I had the script written the way I wanted it, and I had Lance Henriksen in the lead role, so I started thinking about melodies and stuff.” I put together a short film of nature photos I’d taken, set to music. I wanted to show people what it would look like. That helped me shoot and edit it. I’ve edited music before, so I had no idea what image editing was like, but to my surprise, it was very similar – it’s all about rhythm, timing and musicality.”

Mortensen’s epic tale of Vicky Krieps as Vivien is set in the mid-19th century and begins with her untimely death, then jumps back and forth between the stories of her life. The story begins in San Francisco, where she fends off suitors and falls in love with a Danish man named Holger (Mortensen), who whisks her off to the frontier and disappears to fight in the Civil War. In his absence, she creates a home and garden, and does her best to foster a sense of community in a town filled with undesirable ideas and less-than-desirable men. Mortensen’s aesthetic approach is a homage to a different era (widening landscapes set to string sections), but his themes are more contemporary. For a brief but enjoyable 20 minutes, the least-star-of-all-movie-stars of all time talks about westerns, the casting of Vicky Krieps, and the director who influenced him more than anyone else.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

The Film Stage: Congratulations on the finished film. I thought it was so beautiful, with its grand scale, its long timeline and its intimacy. Was it your dream to make a Western like this?

Viggo Mortensen: Not necessarily. I’d done some acting before, and I grew up riding horses as a kid, so that was fun. I’m also old enough to have seen the end of the Western era, which was the early ’60s, around ’62. That’s when they made some really great ones: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. Have you seen the movie The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance?

With Kirk Douglas? Oh, I love him.

Yeah, it’s a great film. But it was a last gasp. It kept getting made. And then, of course, there was a revival in the mid-’60s when Sergio Leone and his Italian and Spanish imitators started making loads of films, which you know were shot in Mexico and a lot of them in Spain. So it was a revival, but it was a kind of reinvention, stylistically exaggerated, photographically striking. The camerawork and everything was different.

I wanted to make a story that fit into the classic Westerns that came before it. Most classic Westerns, like any genre of film, are just awful. I mean, they’re not “bad,” but they’re not very original. Westerns in particular are usually pretty naive and often clumsy because their origins are mythical, and they’re usually representations of exaggerated folklore. So they’re cliché stories, and so you get the same stories over and over again: miners or shepherds versus ranchers; of course, Native Americans attacking poor pioneers; and so on. And then there’s this myth-making about the country that makes people feel safe. And they were very popular, especially in rural movie theaters. People went to see a couple of Westerns every weekend, and they were mass-produced in a few days. The first one was, I think, in 1902, “The Great Train Robbery” or something, but between 1910 and ’62, there were probably 7,000 to 8,000 poems made. Most of them were terrible, but there were a few that were really poetic and beautiful.

Were there any westerns that particularly inspired you while making The Dead Don’t Hurt?

Oh, there are so many, because if I talk about them I’ll probably run out of time. There are a lot of films that you know well, some that you don’t know as well, like Red River by Howard Hawks, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Stagecoach by John Ford. There are some films by Anthony Mann. There’s some good European films, Jack Turner. But I wanted to make a film that was in the vein of the old ones, camerawork-wise. If you know the film, you’ll think, “Wow, this is really well shot,” but it’s not a film that draws attention to itself. And I want to see the details. The best ones are really authentic and look and feel right. So I kept in mind that the big difference from the classic Western is that there’s a woman who is the central character, and when her male partner goes to war, she goes with him, and she’s never a supporting character. He’s invisible. Basically, he’s out of the shot.

Vicky Krieps is perfect for the role of Vivian. What did she bring to this collaboration?

Well, she’s very independent. She has strong opinions on things. She’s very independent-minded and very talented, so you can feel what she’s thinking and what she’s feeling. I felt that when I saw her in the movies. So I said, “Well, I think she’s perfect to play a strong-willed, independent woman in a story where there’s a lot of subtle, unspoken stuff going on.” And to convey that, you need a really good actress with very finely tuned acting skills to convey emotion and to be able to say a lot sometimes without speaking. I don’t know if there are actresses like that available, and you might read a script and say, “This is no good, I don’t like it,” or whatever. She read it and she responded right away and said she liked it and she resonated with it to some extent. She did something that I never dreamed of.

There’s a great scene where your character comes home and Vivian asks, “How was the war?” and you reply, “How was your war?” I thought that was really fascinating to play. There’s so much nuance and so many layers to the way Vicki delivers that line.

That would be devastating.

How did you create that moment together?

That’s how it was written. The idea was not to go with the typical “he comes back, she’s overwhelmed, runs over and hugs him.” They’ve been apart longer than they’ve known each other, so is that going to work? There’s a lot going on with them. That’s why it’s awkward. We already know at the beginning of the story that he’s awkward. He tries, but he’s kind of clumsy sometimes, and they’re both proud and stubborn. So they’re exploring each other. It’s really like the beginning of a new relationship. There’s a lot of information that they can tell each other or not tell each other. So it should all be there. But it’s one thing to imagine it, write it and portray it. It’s another thing to actually make it work on screen and get the audience involved. You need someone like her who never hits the wrong note.

At the beginning, there is a scene where you pick off the thorns from a rose and throw them into your breast pocket. Was that done in one take?

I think I did it a few times, I asked for the knife to be very sharp.

It reminded me of a scene in your other film, Far from Men, set in Algeria, where tea is poured using the traditional loop method. Do you like to incorporate these physical touches to bring color to your characters?

Yeah, I like props. I think props have a life of their own. I like the idea of the rose, that it represents a relationship in a way, and I also like the fact that he keeps it and the audience doesn’t realize it. There’s a scene where he’s writing at night and she comes in and they talk, and the rose is on his desk. He keeps it as if it meant something to him, but it seemed practical. And he seems like someone who is comfortable in nature, like she is.

Of all the directors you’ve worked with, are there any that you would say have influenced your approach to filmmaking?

It would be Cronenberg, in the sense that he is very efficient, knows what shots are good, and makes editing a lot easier. He is the most organized in terms of knowing in advance. When he arrives on set, he immediately knows exactly what he wants to do. I have worked with directors who are organized, calm, and communicate well with their crew and peers. I have also worked with directors who didn’t know how to talk to actors, or were afraid of them, or always communicated with the crew through someone else. Or maybe they are trying to maintain some kind of sense of authority by doing so. But I think it’s really beneficial to be clear from the beginning. I have a very clear idea of what I want to do, but if someone has a better idea about something, speak up. Don’t tell me tomorrow, because it’s too late.

“The Dead Don’t Hurt” is currently in limited release.