The history of Chicago and Eastern Illinois was special to those who witnessed the railroad firsthand.

C&EI’s Florida Varnish was “comparable” to the Star Santa Fe among the seven lines at Chicago’s Dearborn station, but the unnamed No. 1 bound for Evansville was inferior. With ATSF rolling stock in the background, the local departs in April 1957 with an NC&StL baggage car behind two FP7-E7 cars. Dan Pope Collection

C&EI’s Florida Varnish was “comparable” to the Star Santa Fe among the seven lines at Chicago’s Dearborn station, but the unnamed No. 1 bound for Evansville was inferior. With ATSF rolling stock in the background, the local departs in April 1957 with an NC&StL baggage car behind two FP7-E7 cars. Dan Pope Collection

“Chicago” has often been a magic word in the names of great railroads. Think of all the carriers that bore Chicago on their letterheads, those that charted thousands of miles on their maps, those whose names alluded to vast intercontinental distances: Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific; Chicago, Milwaukee, St. Paul & Pacific; Chicago & Northwestern; or those that, at some point in history, struck gold in some way: Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, with its incomparable Zephyr; Chicago South Shore & South Bend, Chicago North Shore & Milwaukee, with their roaring, high-speed interurbans.

And then there was the Chicago and Eastern Illinois Railroad, with a name as practical and ordinary as it gets. The C&EI pretty much lived up to its name, running due south from Chicago through the cornfields along the Illinois-Indiana border. Its route map resembled a trident, with two main lines splitting at Woodland Junction, 64 miles south of Chicago, leading southwest to St. Louis and south to Evansville, Indiana, and a secondary line that branched off from the St. Louis line and continued straight south to the “Egypt” region of southernmost Illinois. The C&EI was headquartered in Chicago, with its operating base in Danville, 123 miles south.

The C&EI was often described as a respectable but unremarkable company. Throughout most of the 20th century, its revenues placed it in the middle of the AAR’s list of Class I railroads. In 1940, its line mileage was a modest 925 miles. It was a minor presence at Chicago’s Dearborn station and even more so at St. Louis Union Station. During the steam era, the C&EI operated a conventional fleet of locomotives, mostly 2-8-2s and 4-6-2s, and never had locomotives with four-wheel trailing trucks. The C&EI went diesel after World War II, using mostly off-the-shelf EMD F units, Geeps, and switchers, with three BL2s and four Alco RS1s to spruce up the mix. The C&EI’s overall appearance led his friend George H. Drury to write that it was “mediocre.”

George meant no harm. In his essay “Unremarked, Unremarkable” in the July 1983 issue of Trains magazine, he explained that mediocre means “neither particularly good nor particularly bad.” (And this is coming from a guy who loves the Boston & Maine!) Ed DeRuin, in his book Chicago & Eastern Illinois Railroad in Color (Morning Sun Books, 2001), calls the railroad “conventionally mediocre.”

The core of C&EI’s early road diesel locomotive fleet was 33 F units and 30 GP7s, two of which are shown in southbound transit at Chicago on June 25, 1961, as seen from Monon’s Thoroughbred. Photo by J. David Ingles

The core of C&EI’s early road diesel locomotive fleet was 33 F units and 30 GP7s, two of which are shown in southbound transit at Chicago on June 25, 1961, as seen from Monon’s Thoroughbred. Photo by J. David Ingles

The railways of my youth

I have concluded that George and Ed were wrong, coming from someone who, as a nine-year-old, spent many happy summers walking along the gleaming double-track main line of the C&EI that straddled the quiet farming town of Alvin, Illinois, the hometown of my Aunt Bessie and Uncle John.

My great-aunt, Bessie Allison, was a kind but stubborn woman who cooked on a coal stove, pumped water from a hand pump on her front porch, and once worked as a caretaker for the C&EI at Alvin Station, a few hundred feet from her home at the crossing of the Illinois Central Railroad’s Rantoul & Eastern Branch (defunct in the 1930s). Her husband, John Allison, was also a C&EI retiree, a skinny little man who had done years of backbreaking labor as a section man. (Full disclosure: my paternal family is all deeply entwined in Chicago and Eastern Illinois history. My great-grandfather, Peter Keefe, was a leverman, and his son, my grandfather, Edgar Keefe, was an operator who retired around 1951 and finished his career at the train dispatcher’s office in Danville.)

My family trips to Alvin from Chicago, and later southern Michigan, in the late 1950s and early 1960s were like visits to the turn of the century. Although Aunt Bessie’s hospitality was generous, I wasn’t very excited about the relatively primitive surroundings, especially the outhouse in the back. Still, every trip to Alvin was enjoyable, thanks to the excellent entertainment provided by the C&EI.

The tracks ran north and south through town, crossing West Railroad Street a half block west of our house. I don’t know how busy the C&EI was in those days, but I remember long summer afternoons frequently interrupted by the distant sound of an air horn that would make me drop whatever I was doing, leave my brother and sister behind, and run down the street to catch the hazy vision of the blue-and-orange cab and silver passenger car roaring through town. The sight and sound were mesmerizing.

Yes, little C&EI had a magnetic appeal, and not just to 9-year-olds. In fact, as I’ve learned over the years, the railroad could claim some superiority that helped it, at least to me, transcend its mediocre roots.

Take passenger trains, for example. While the C&EI shared the most prestigious livery glory with many partners, including Louisville & Nashville, Nashville, Chattanooga & St. Louis, Atlanta, Birmingham & Coast, Atlantic Coast Line, and Florida East Coast, the C&EI hosted them in Chicago, providing the Windy City with premium train service to Florida. These famous C&EI trains included the Dixie Flagler, Dixie Flyer, and Dixie Limited, as well as the exotic southern-bound streamlined L&N Georgians and Humming Birds, which gave Santa Fe’s more famous Chiefs a run for their money.

Chicago and Eastern Illinois history also featured worthy domestic trains, such as the postwar streamliners the Meadowlark and Whippoorwill. Built by Pullman-Standard and introduced in 1946, the Meadowlark ran daily between Chicago and Cypress, 345 miles south, while the Whippoorwill linked Chicago with Evansville. Both trains debuted with their usual fanfare, but the Whippoorwill had been relegated to an Evansville local by 1950, and the Meadowlark only lasted until 1962, by which point it was equipped with the railroad’s only Budd RDC-1.

At one time, the C&EI was battling three competitors in the tough Chicago-St. Louis market. By the 1930s, the line was already well served by the Alton, Illinois Central, and Wabash. The C&EI entered the fray with the Zipper, which performed well, covering the 290 miles in five hours at an average speed of 58 mph. The Zipper offered a train that left Chicago at 5:00 PM and St. Louis at 8:50 AM (“first out, first in,” the railroad said of its morning train). But with this performance, the C&EI could only boast of being the “fastest standard-weight train” on the line, as the IC beat it by five minutes with its new “diesel-electric articulated streamliner,” the Green Diamond. Shortly after the war, the C&EI gave up on the St. Louis market.

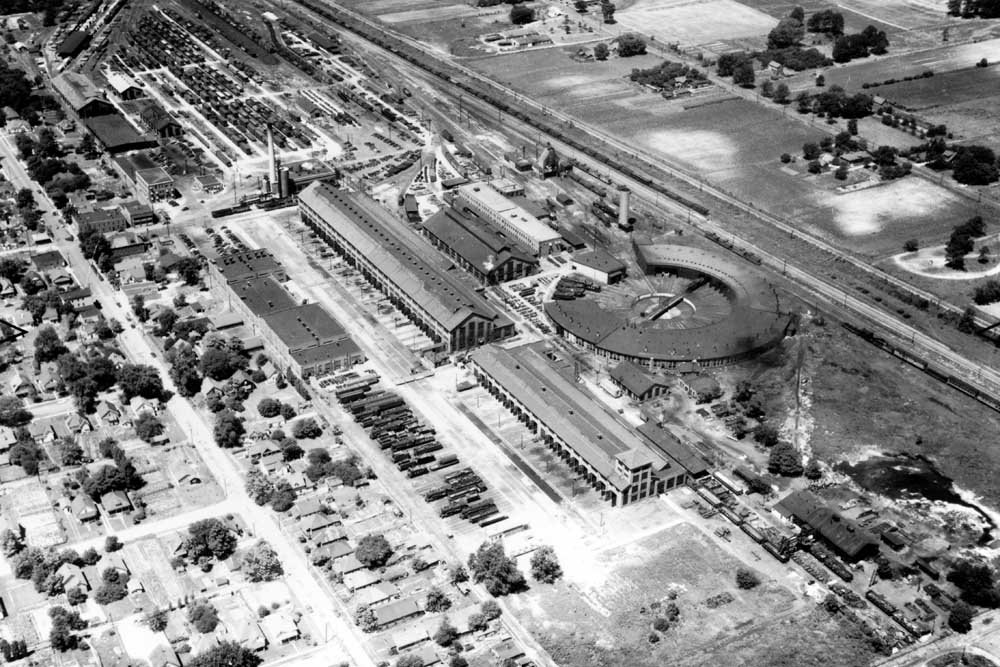

An integral part of Chicago and Eastern Illinois history, the Oak Lawn Shops were located in Danville, Illinois, as seen in this circa 1948 photo. The shop survived a devastating fire in November 1937, converted entirely to railroad car repair in 1950, and closed in 1969. Jay Williams Collection

An integral part of Chicago and Eastern Illinois history, the Oak Lawn Shops were located in Danville, Illinois, as seen in this circa 1948 photo. The shop survived a devastating fire in November 1937, converted entirely to railroad car repair in 1950, and closed in 1969. Jay Williams Collection

Modest power, large shop

Home to the C&EI’s modest motor fleet was a modest place called Oak Crown Shops on the east edge of Danville. Built in phases in 1903 and 1907, Oak Crown Shops was a vast facility rivaling those in Roanoke and Altoona, with a 628-foot-long machine and assembly shop, an associated carriage shop, a boiler shop, and a 56-stall engine shed. Shop workers could do more than just routine maintenance. In 1940, they completely streamlined and modernized the 29-year-old Baldwin USRA Pacific No. 1008 to run on the Dixie Flagler, a new passenger streamliner on the Chicago-Miami route. The old K-2 Pacific was fitted with new Scullin disc drive wheels, cast steel drop coupler pilots, and sleek black and silver Skyline casings.

The C&EI was not just a typical Midwestern freight carrier. Of course, it also transported agricultural products and expedited the delivery of goods to Chicago and the surrounding area. But it also had a unique history with another commodity: bituminous coal. After 1911, the company absorbed several smaller carriers in southern Illinois and Indiana to service the coal mines. By the 1930s, competition from cheap coal from the Appalachians had significantly reduced C&EI’s traffic, but by the mid-1950s, traffic had surged again to meet the demands of new power plants in Danville, Terre Haute, Indiana, and along the Ohio River.

Coal also fueled a strange but important footnote in the history of the Chicago Eastern Illinois Railroad: the Elgin, Joliet Eastern Railroad’s use of 100 miles of trackage rights from the C&EI to develop the coalfields. The agreement dates back to 1893, when the U.S. Steel-owned EJ&E began running three or more coal trains a day from its small terminal on the C&EI main line at Rossville Junction, Illinois, 105 miles from Chicago. From Rossville, EJ&E served several USS-owned coal mines near Westville, Illinois, and Jackson, Indiana. The Great Depression hit EJ&E’s coal operations hard, and despite an economic recovery during World War II, the “J” was moving toward dieselization, so the agreement ended in 1947.

Alas, the history of the Chicago Eastern Illinois Railroad was, so to speak, “cheerful” and it never managed to remain independent as a corporate entity. After the C&EI recovered in 1920 from its 1912 bankruptcy caused by Frisco, the new C&EI struggled under the ownership of the Van Sweringen brothers of Cleveland, and went bankrupt again in 1933. The new C&EI appeared in 1940 and remained independent until 1963, when the ICC gave control to Missouri Pacific, with the stipulation that it transfer the Evansville line to the L&N, effective in 1969. Thus, the C&EI gradually lost its identity to its two successors, this time by merger, giving way to today’s Union Pacific (formerly St. Louis and Cypress lines in Mopac) and CSX Transportation (formerly L&N to Evansville).